LAST YEAR, THE FIRST Chinese American movie star was saddled with yet another pioneering honorific: Anna May Wong became the first actress to have the figurative currency of her face made literal, minted on a US quarter. This star, born on silver nitrate, found an afterlife in copper-nickel. I can think of no wrier fate for someone trailed by so much ornamental simile, most often compared to things: Wong’s ex-lover Eric Maschwitz thought her “a piece of porcelain”; Walter Benjamin called her a “chinoiserie specimen” and likened her name to “full moons in a bowl of tea.” I am doing laundry the first time I see her blunt fringe on a quarter, gleaming and banal.

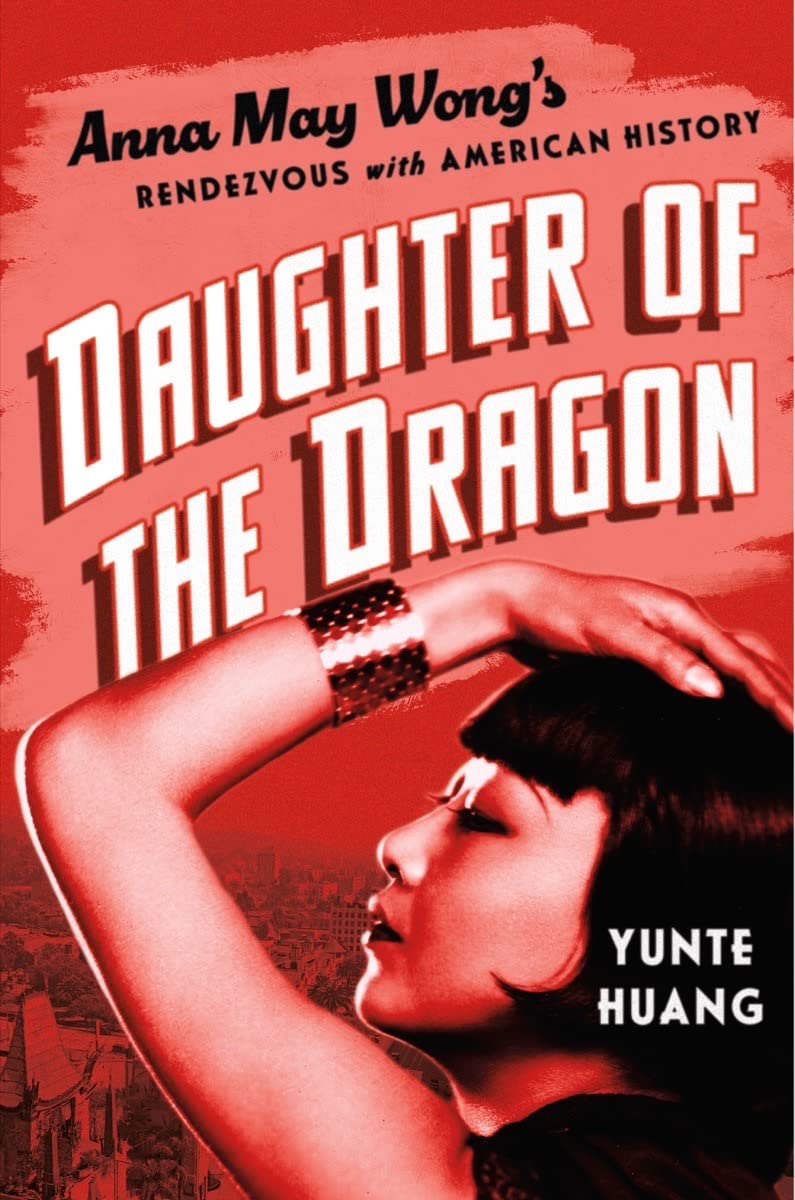

Wong’s coinage is a loud and belated moment of civic recognition. Here is a national treasure, it says, an American seeker of an American dream. There is a similar gesture of reclamation in Yunte Huang’s new biography of Wong, the final installment in his trilogy about the controversial legacies of Asian American cultural icons during “the making of America.” Huang focuses on the mid-nineteenth to early-twentieth century, when waves of mass immigration from Asian countries coincided with wholesale transformations of American visual culture. At this juncture, Otherness was aestheticized and recast as spectacle or commodity in order to contain its perceived existential menace, reduced to lacquered collectibles or fairground intrigue. In his biography of Wong, Huang continues to explore how racial anxieties were displaced onto sites of exhibition and display, increasingly mediated by the new technologies of photography and cinema. Like his 2018 book on Chang and Eng Bunker, the “original Siamese twins” brought to Boston in 1829, Daughter of the Dragon also works as a study of vernacular origins, its very title drawn from the 1931 film that would become Wong’s archetypal peak. To parse these primal scenes of stereotype—“Siamese twins” and “dragon lady”—is to unravel the entwined production of race and visual culture.

In his telling of Wong’s rise in the late silent era, Huang baits us with the shiniest pieces of her mythos while describing the vexing conditions under which she came to be seen at all. Early cinema, he points out, often sourced its thrills from other “exotic” novelties, like the cramped tenements of Chinatown and steam-clogged Chinese laundries. Soon, Wong herself was given a perch in the nation’s oriental imaginary. Though she is the book’s organizing interest, Wong often disappears behind reams of epochal précis that span half a century of Chinese Exclusion Acts, California’s anti-miscegenation laws (on- and off-screen), and more than one international conflict. After all, Huang’s premise is stitched into the subtitle: “Anna May Wong’s Rendezvous with American History.” This works because it’s all in service of Huang’s true subject, to which he always returns: the strange ambivalence that marks any racialized performer’s ascent to fame. Wong’s star image was built on endless contradictions that, at times, rattled her sense of self.

Wong was born in 1905 to a Cantonese immigrant and his second wife, on the outskirts of LA’s Chinatown where he ran a laundry business. Like so many other “movie-struck” girls, Wong was in thrall to a flickering dream, skipping school to shadow film crews whenever they came to the neighborhood. Wong entered her twenties with two landmark credits to her name: at seventeen, she starred in The Toll of the Sea (1922), Technicolor’s first commercial and technical success; by nineteen, she’d stolen the screen at home and abroad as a Mongol maid in The Thief of Bagdad (1924), slinking around sheathed in mystery and not much else. After that film’s roaring reception in Germany, she caught the twilight years of Weimar Berlin, where she made a few films and parlayed her racialization into exotic intrigue with the winking sign-off, “Orientally yours.” She stopped by Paris en route to London, where, in 1929, she sealed her fate in Piccadilly as Shosho, the dishwasher-cum-showgirl whose story, as Huang and others have noted, sounds a lot like Wong’s own. One night, she’s caught dancing in a nightclub scullery by the venue’s proprietor. Soon, he lets her onstage in an ornate costume of her own choosing. With every shimmy, Shosho’s metallic surface catches the spotlight and doubles her luster. The room goes wild, raining applause.

So the daughter of a migrant laborer went on her own peregrinations. “Wong had to go to Europe to be recognized as American,” Huang writes, “to Australia to be hailed as Chinese,” but everywhere, she was a vision. Wong returned to LA with a little French, German, and some choice affectations, but her real coup was a newfound fluency in her own visual idiom. Wherever she went, she was a test of the public threshold for difference, and where she found that tolerance wanting, she knew that glamour could make her legible, corral the dissonant signifiers of her Chinese face and California twang into stunning, cosmopolitan coherence. She had the “uncanny ability,” Huang notes, “to turn working-class aesthetics into high class symbols,” though she knew just as well what to leave in the dust. When her stage debut in London drew criticisms of her “guttural and uncultivated” Yankee accent, she took pricey elocution lessons and entered the talkies a year later, larynx wrapped in the accent of her Oxford-educated instructor.

She had more than one name and no say in the first two, born Wong Liu Tsong and dubbed “Anna” by the presiding doctor. On her way to fame, she pulled over and picked up an extra syllable because “Anna May Wong” sold a better marquee fantasy. Every hopeful ingenue passes through these familiar rites of self-fashioning, but Wong would always hold that first name close. In 1936, soon after she lost the role of a lifetime to an actress in yellowface—the lead in MGM’s $2.8 million Orientalist extravaganza The Good Earth—she ran off to the motherland, trying to figure out, as she told the San Francisco Chronicle just before her departure, whether she was “really Anna May Wong or Wong Liu Tsong.”

She was both, or she was neither. Even Huang can’t settle on what to call her—his prose is swarmed by the many epithets she inadvertently prompted and ossified into racial stereotype: “China doll”; “laundryman’s daughter” (used in the title of Graham Russell Gao Hodges’s 2004 biography of Wong); “Dragon Lady” (echoing this book’s red herring of a title). Huang summons her monikers critically, approaching Wong’s iconography as an index of the public’s fears and desires. But at times, he can be too generous—even anachronistic—in his defense of her caricature-laden filmography. In a densely academic section, he claims that she “drew attention to or even exploded the stereotype by overacting these roles.” Huang is not alone in such redemptive readings of Wong’s performances, but there’s no pressing need to redeem a career so clearly constrained by historical circumstance. The same industry that opened Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in 1927 (“a monument to Hollywood’s lasting China fever”) had begun to self-censor by 1934—the Hays Code’s stipulation against depictions of interracial romance stalled Wong’s career mid-launch. “No China flick could do without her,” Huang writes, “but no director could feature her as the lead.”

In the mid-1930s, when Hollywood sailed into its golden age and nudged her into peripheral roles, Wong continued to “project her star power via fashion.” Her glamour, Huang shows, was enhaloed by superlatives and stratospheric esteem: “The World’s Best Dressed Woman” in 1934; “The World’s Most Beautiful Chinese Girl” in 1938. But she had been a fraught locus of visual pleasure since her earliest roles, her racialized femininity entangled with the mise-en-scène. As Lotus Flower, Shosho, or Princess Ling Moy, her beauty was sutured to the oriental regalia of embroidered silks and metal filigree, exemplifying what scholar Anne Anlin Cheng has called “ornamental personhood.” It was not until her trip to China that Wong began to unfasten her sense of self from the pageantry, returning to California with a trove of tailor-made cheongsams. When she told the Hong Kong Telegraph that she’d “never worn real Chinese dresses before—only costumes,” she meant “real” as in authentic, but she might as well have meant prosaic. Familiarity turns costumes into ordinary clothes.

In still and moving pictures, Wong’s presence appears firm and declarative, but in words we find her troubled by what her image has been made to say. To let Wong “speak for herself,” Huang often pulls quotes verbatim from interviews and much of her own published writing—most notably from a series of travel dispatches commissioned by the New York Herald Tribune before she left for China. She seems unsettled by the phantom entourage of her varied personae, searching the looks of untold others for a way of looking at herself. “I seemed suddenly to be standing at one side watching myself with complete detachment,” she told the Los Angeles Times of that early jaunt in Berlin. “Up to that time I had been more of an American flapper than Chinese.” When she landed in her paternal hometown of Taishan, the locals received her with disbelief: “Many women could not believe I really existed,” she later relayed, “they had seen me on the screen but they thought I was simply a picture invented by a machine.” But the Wong whose voice I want to hear the most—older and wearier, I imagine, made sharper by retrospect—never appears. The quotations trail off after 1936 and end in 1943, with some of her notes on Chinese cooking. Huang crams the last twenty years of her life into just three of the book’s forty chapters, careening through her career’s postwar stasis, her brief stint in television, and her quiet end as a dipsomaniac landlord in Santa Monica.

While reading, I catch myself collecting mentions of Wong’s birth name. It sneaks on-screen in Piccadilly, when “the heroine Shosho signs Anna May’s Chinese name as if it were her own,” appending her anglicized sign-off with “Wong Liu Tsong” in Chinese script. The calligraphy is awkward and gaping, strokes made by an uncertain hand. Who was in on this, back then? Who looked at the sum of those lines and saw a name, not a piece of chinoiserie? It appears again in 1951, when the soon-defunct DuMont Network cast her as the lead in its television series, The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong, but those reels were flung into the East River when the company shuttered. “When I die,” Wong quipped two years before she did, a quote so famous it does not appear in this book, “my epitaph should be: I died a thousand deaths. That was the story of my film career.” But she hardly has a grave, never mind an epitaph—in the epilogue, Huang takes us to Angelus Rosedale Cemetery, where she appears as a single line on a shared tombstone: “Daughter, Liu Tsong.” I look for that name because, like her, I was also born with a different one, and no one has said it in years.

Phoebe Chen is a writer in New York.