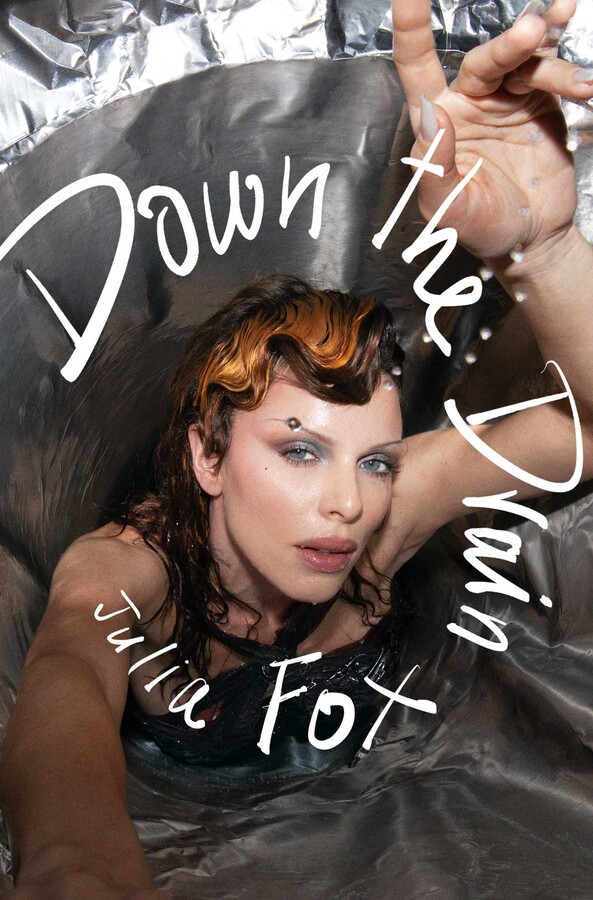

“WHO IS Julia Fox?” This is the question taken up by Fox’s highly anticipated memoir Down the Drain (Simon & Schuster, $29)—so highly anticipated, in fact, that I was required to sign an NDA promising I wouldn’t leak any details from the press copy I received, the plain white cover of which read only, enticingly, EMBARGOED. It was also the question some of my, frankly, uncool friends and acquaintances asked me when I excitedly told them I was reviewing Fox’s book. “Josh Safdie’s muse?” I prompted. “Actually, she’s her own muse. You know . . . Uncut Gems?” I pronounced it “unkah jamz,” as Fox once did in a heavily memed podcast interview; this only increased my interlocutors’ confusion. “Weird eye makeup? Kanye???” This usually cleared things up.

But the answer to “Who is Julia Fox?,” Julia Fox wants us to know, is not “Kanye???” Despite the fact that briefly dating the rapper currently known as Ye is arguably Fox’s only claim to fame, the relationship is confined to fifteen pages near the end of Fox’s 318-page book, and he is referred to not by name but as “the artist.” The artist this book is really about is Fox herself: the proud Italian American actress, photographer, filmmaker, downtown-scene fixture, fashion designer, and now writer whose primary medium—even when she’s not decorating silk canvases with her own blood, as she did for a 2017 art show called R.I.P. Julia Fox—is the self.

Down the Drain begins with six-year-old Julia’s arrival with her father on the Upper East Side after an early childhood spent outside Milan, where she was born, and narrates her coming of age between New York and Italy, where she loses her virginity to a Casanova she calls Giovanni (most names have been changed). Money is short, adult supervision is absent, and, when a girl has the face of an angel and a body for sin, Manhattan is the devil’s playground. But Julia’s formative years aren’t all sex, drugs, and shoplifting: pleasure mixes with the pain of childhood neglect, intimate-partner abuse, addiction, near-overdoses, the untimely deaths of several close friends.

Fox is best known for her idiosyncrasies—her latex-forward fashion, her raccoon-eye makeup, her unusual way of pronouncing “uncut gems”—and the book is not without bizarre details (squeezing shit from an enema bag into a rival’s locker while working in a dominatrix dungeon, for example). But the overall image she presents of herself is almost archetypal. Like Christ, but more like a female medieval mystic trying to be like Christ on the cross while also having erotic visions of Christ in bed, she suffers endlessly and sometimes ecstatically for the sins of others, her body a vessel for passion in every sense of the word. Being your own muse can mean making a subject out of your subjection: when you reify yourself into the ultimate It Girl, utterly neutral and utterly feminine, you become a pronoun onto which anything can be projected.

This singular commitment to universal blankness might be why Fox’s memoir reads like a collage of the most generic genres, a bit like the “Oxen of the Sun” episode in James Joyce’s Ulysses if instead of the historical development of literary style Joyce had decided to parody every contemporary form of formulaic writing. It’s part preteen’s diary (“Score! I’ll wait until everyone is asleep and log on to AIM”), part probation appeal (“It’s never too late to change your life”), part DEI statement (“As a white woman, I feel a sense of duty to join the fight and stand in solidarity with the protesters”), part twelve-step testimonial (“Ace has such a hold on me. He’s my favorite of all the drugs”), part college-admissions essay (“Her passion is infectious as I too begin learning more of the injustices committed by our government”), part Instagram influencer sponconspeak (“I love living on Bleecker Street, buzzing with electricity in the heart of the Village”), part Creative Writing 101 assignment (“The humidity hangs heavy in the air, clinging to my skin like a sweet sticky veil”), part self-published erotica (“We have the most exhilarating sex ever,” “sex like we are the last two people on earth and the human race depends on it,” “sweet passionate lustful orgasmic sex”). The banalities pour out like ink flowing onto the page; they pile up like a frosty mountain of cocaine; they crush the reader like a pile of bricks. The sheer accumulation of hackneyed attempts at authenticity makes Fox sound neither like a garden-variety celebrity whose ghostwriter has dutifully trotted out the relevant clichés nor like a true original weirdo, but like a machine desperately trying to iterate itself into personhood and going off the rails. This is somebody who wants to be somebody, even if somebody sounds like everybody. There’s something superhuman about the intensity of Fox’s drive to generic subjectivity: her voice is the voice of an AI generation.

Her title comes from Rohan, a sugar daddy with a heart of gold, who warns her, “You’re throwing your whole life down the drain,” a phrase that echoes in Fox’s head as if it were an immortal line of poetry and not a pat paternalistic admonition. Best friends and boyfriends blur. Particularity emerges only when Fox’s stock-phrase-generator seems to malfunction. An elementary school classmate’s notes “look like a gel-pen purple paradise,” which was a new kind of paradise for me. When she’s humiliated in front of the class on her first day at her Italian high school, she’s met with “gasps around the room harmonizing like a shitty choir,” the discord between “shitty” and “choir” making the noise sound truly bad. Describing a romantic encounter with Rohan, she says, “he kisses my hand all the way up my arm and into the nape of my neck à la Gomez from The Addams Family,” as if trying and failing to finish the sentence with a straight face. When Julia arrives with Ace, her controlling and abusive boyfriend on the run from the law, at the home of his mother, she “greets us at the door, draped in a pink silk robe with a glass of red wine in one hand and a lit cigarette in the other. The scene is straight out of a film noir,” a genre famously defined by moms drinking wine.

When the personal is the professional, where’s the line between living your life as a unique work of art and cynically self-branding like countless others? During her brief stint as a dominatrix, Fox discovers her talent for pretending to be other people (“I transform into your mean mommy, an evil nun, the bitchy popular girl in high school, all in a day’s work”). With Rohan’s help, she starts a fashion line. (Fox claims, in a since-deleted TikTok, that the Kardashians, of whose show she’s an avowed fan, were clients.) Out of her own dark materials she makes an autobiographical art book, “cutting, gluing, and scanning” photographs and other documents of her doomed affair with Ace. When she’s cast in Uncut Gems, she reflects on how, the night before Ace turned himself in, they stayed up late watching Adam Sandler movies. Now she’s in one, and at her screen test with Sandler, for a character whose name the Safdies changed to Julia, “the moment I saw those lights and the cameras, a switch went off and I was Julia Motherfucking Fox.”

It’s a role she was made for. In real life, or life mediated by non-print media, Fox is fantastically fascinating. Those who dismiss her as almost-famous-for-being-famous, trying and failing to keep up with the Kardashians, miss how perfectly she’s mastered her metamorphic art of self-fashioning. On social media, Fox seems not so much in control of her image as she is savvy about letting others take it over, hyper-aware of her memeability. Fox’s prose may sound like everybody, but everybody wants to sound like her. Like her “unkah jamz” moment, which inspired hundreds of people to record themselves murmuring “unkah jamz . . . unkah jamz . . . ” while sitting at the computer or performing household tasks, Fox’s 2022 Oscars red carpet interview about her signature look quickly became an internet imitation game. “You always have that strong eye makeup,” the interviewer coos. “Is that you? Or do you have a makeup artist who does it for you?” “I actually did it myself . . . yeah,” Fox responds. “Nice!” the interviewer affirms. “Yeah . . . ” Fox says again, smiling. I found myself watching a seven-minute, thirty-six-second YouTube compilation of TikTokers mouthing Fox’s line, “I actually did it myself . . . yeah . . . yeah . . . ” lip-synched against background text about self-sabotage or confident incompetence: “~what’s wrong who made you cry~ I actually did it myself . . . ”; “~16 year old me in the club smoking area showing off my ID I faked by sticking a 0 over the 2~ I actually did it myself. . . . ” As I write this piece, I sometimes keep this mantric chant on loop in the background (“I’m actually doing it myself . . . ”), every e-girl speaking in the voice of my girl.

Rewatching Uncut Gems after reading Down the Drain, I tried to find the Julia behind the Julia. There’s a scene at a club where The Weeknd, playing his 2012 self, is performing as Julia nods along, her white top glowing in the blacklight. When Sandler’s character finds her in the bathroom with the singer, an altercation ensues (“We were just doing coke!” Julia pleads). He abandons her, she tearfully runs after him, he gets in a cab and calls her trash. It sounds like any number of sad scene-making scenes in Down the Drain, art repeating the repetition compulsions of life. As a tracking shot follows Julia huffing back toward the club, she barks at the anonymous gawkers outside, “What the fuck are you looking at!” “Nothing much,” someone responds off-camera. “Oh, funny, stupid bitch,” Julia shoots back, afraid they might be right, doing everything she can to prove they’re not.

Katie Kadue is a critic from Los Angeles.