WE LIVE IN CONFESSIONAL TIMES and the self-exposure bug eventually comes for us all, the steeliest of non-disclosers, no less. We age and turn inward, we become garrulous and spill. Even I, who once fled the first-person singular like a bad smell, now talk about myself endlessly in print, opening every essay or review with some “revealing” anecdote or slightly abashed confession, striving for the perfect degree of manicured self-deprecation and helpless charm. Needless to say, the more forthcoming you appear, the more calculated the agenda, not always consciously.

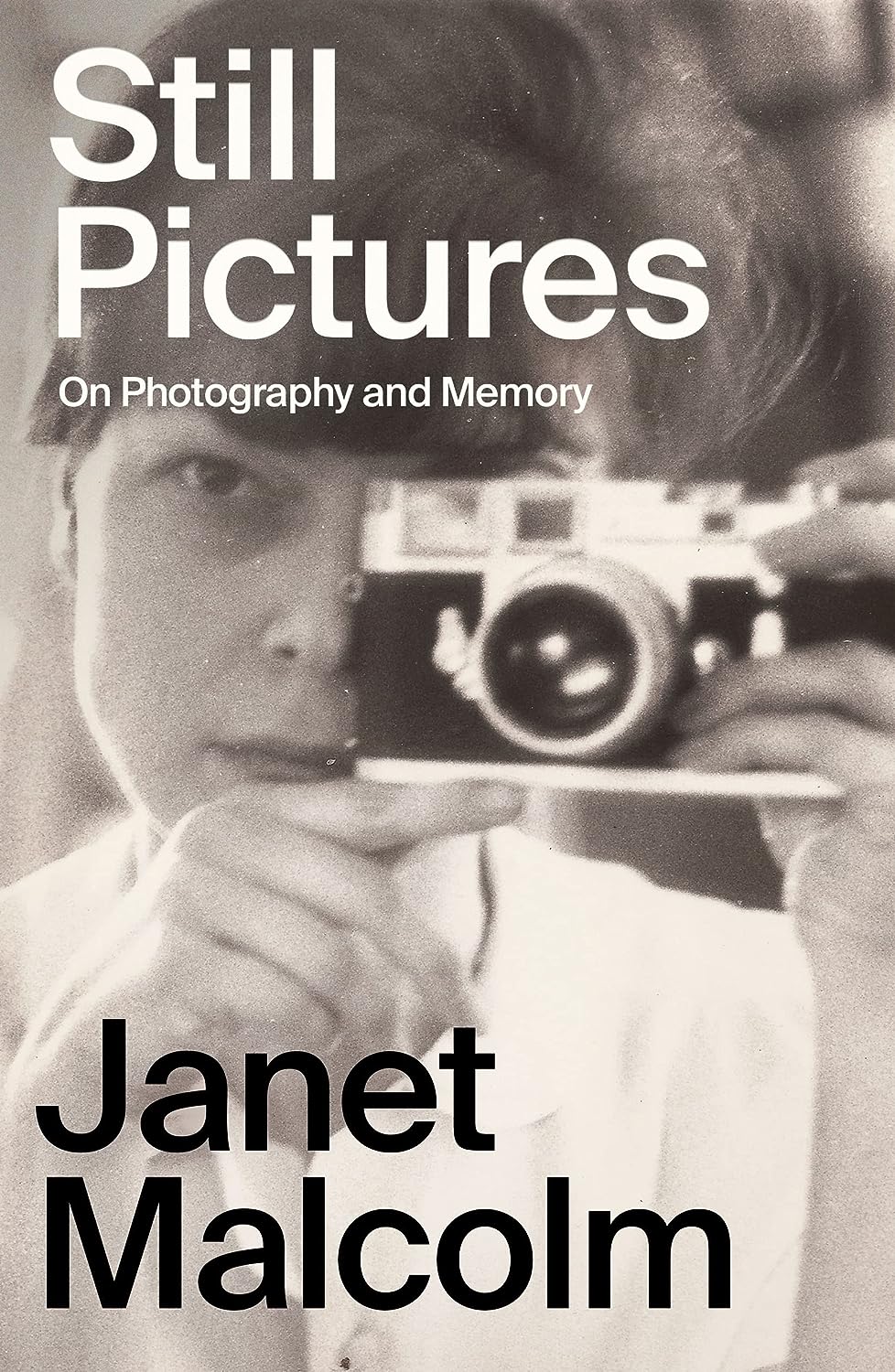

Which brings me to Janet Malcolm’s posthumously published collection of autobiographical fragments, Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory. Malcolm, who died in 2021, enjoyed a pretty tight-lipped career when it came to dispensing biographical data points. She was a writer singularly and supremely herself in every sentence; you didn’t require the grubby personal specifics to feel you knew her well. Indeed, other people’s compulsions to confess things they probably shouldn’t was the meat and bones of her reported pieces and profiles, including such inadvertent “confessions” as an inapt word choice, a chaotic love life, or an overly self-conscious item of living room decor, all of which became, in Malcolm’s hands, a window onto some hapless striver’s soul. She was good at revealing people to themselves; not all her subjects loved that about her. A big chunk of what I know about the art of creative inference I learned from Malcolm, who practiced it deftly (sometimes ruthlessly). I’m not sure I’d call the quality of forensic scrutiny she brought to the enterprise a form of deep optimism about the human plight, the underlying premise being that people are engineered for deception, and that self-deception is just the frosting on the cake.

Even so, I was charmed and lulled by Malcolm’s late-in-life memoirish turn: mostly half-remembered reminiscences of her family, childhood, and adolescence, from Nazi-occupied Prague to émigré New York. And then along comes “The Apartment,” toward the end of the volume, where we find Malcolm confessing, in a rather startling departure from her longstanding . . . Malcolmishness, to an adulterous relationship with “G” in the early 1970s. “Adultery takes one out of one’s usual life, sometimes in unusual ways,” she says of their weekly—sometimes twice weekly—guilty midday trysts, which moved from a seedy midtown hotel (the Belvedere) to a seedy one-room apartment rented for these assignations. They furnished it with a bed, two chairs, two plates, two wineglasses, etc., which were—this being the West Fifties in a notoriously crime-riddled decade—stolen one by one by a thief who crawled in through a window. Even the bed eventually disappeared, after which they gave the place up. She casually reveals that “G.” was Gardner Botsford, Malcolm’s New Yorker editor for over ten years, who later became her second husband.

I have to presume other Malcolm afficionados reacted as I did. Is it too much of a cliché to say “jaw hit floor”?

Why on earth is the exceedingly private Malcolm confessing to a prolonged extramarital affair now, decades after the fact? On her deathbed? The piece was occasioned, she says, by a memory of those two plates—Italian china with a faux folk-art flowery pattern (not her usual taste)—that have suddenly appeared in her mind’s eye for reasons she knows but won’t reveal. “I would rather flunk a writing test than expose the pathetic secrets of my heart,” she teases the reader. “The prerogative of cowardly withholding is precious to the most apparently self-revealing of writers. I apologetically exercise it here.”

Note that “apparently.”

I knew Malcolm slightly—I’d been to her palatial apartment a few times for gatherings she’d hosted, we’d chatted on occasion—but it hadn’t previously occurred to me to be interested in her love life. Yet reading “The Apartment” made me feel like an aging gentleman in a music hall watching a skillful coquette do the cancan—a mischievous flash of thigh, the swoop of a raised petticoat—craning my neck to see more, to the point of inducing a cramp. People are in many respects dismally predictable; voyeurism and vicariousness are hardly unknown in our species. One assumes that Malcolm, as psychoanalytically schooled as anyone in her grasp of human prurience, could hardly feign innocence about the dynamic she was putting in motion. She’d inflamed my curiosity and now I wanted to know everything. I needed to know the pathetic secrets.

I’d been vaguely aware that both Malcolm’s husbands had worked at the New Yorker and that she’d been widowed twice, but the news of an office romantic triangle in the storied years of Mr. Shawn’s New Yorker further incited my curiosity. Did the rest of the office know? Was there gossip? Did the respective spouses know or learn?

And what about the husband Malcolm had been stepping out on, Donald Malcolm? How had it been between them? On this Malcolm is silent. Naturally, I looked up the obituaries. The New Yorker tribute—unsigned, though apparently written by Mr. Shawn himself (whose own office affair with New Yorker writer Lillian Ross has, of course, been the stuff of enduring legend)—is a masterpiece of elegantly muted tragedy. Astonishingly talented as a writer, one of the best the New Yorker had ever published, Donald had been overtaken by “a succession of medical quandaries” a decade earlier, from which he’d never recovered. He was dead at age forty-three. Though never succumbing to invalidism, his physical world had ultimately contracted to one room, a television, and some sheets of paper. “Thrown back upon himself, he peered into the secrets of human existence . . . and by the end he knew more about pain than anyone should have to know.”

An interesting line of inquiry for Malcolm’s future biographer, not that I’m auditioning for the role, is that this detailed encomium fails to mention his roughly two-decade marriage to Janet. Nor does the New York Times obit, which pointedly fails to list Janet among Donald Malcolm’s survivors: a mother, a brother, and a daughter. She and Donald would appear to have been separated at the time he died (“Thrown back on himself,” Mr. Shawn had written), but was it his family that dictated the omission of her name to the Times? Was it Janet herself? Had someone deemed her insufficiently wifely to be counted as a survivor? I wondered if news of the affair with Botsford had emerged or been confessed, and at what point in the chronology of “The Apartment”—before or after the festive Italian plates had gone missing? If she’d made the painful decision to leave a chronically ill husband, what family and social fallout would that have entailed, and what would all this have been like for her to go through? Whatever precisely transpired had to have been agonizing and messy, far more so than the rather whimsical tone of “The Apartment” conveys. Was that its agenda—papering over pain with whimsy? The more I reflected on the oddity of its literary construction the more it seemed like a complicated piece of misdirection: summoning your attention to one thing (crockery) while steering it away from something more crucial.

Botsford appears to have been a dashing and convivial fellow: a World War II hero, not to mention rich—a stepson of Raoul Fleischmann, the New Yorker’s original wealthy backer and publisher (the money was from Fleischmann’s Yeast). Malcolm and he married in 1975, the year after his first wife’s death and the same year as Donald’s, which would generally be seen as rather a quick turnaround for a recent widow. Botsford’s Times obit quotes Roger Angell on the second marriage: “Their love grew out of editing.” On the subject of interoffice triangles, I wondered if Botsford was Donald’s editor as well. That too could have been quite a mess.

Speaking of literary oddity, in the course of “The Apartment” Malcolm offers another confession, this one on behalf of Botsford, about a fling he’d had while visiting Paris after the war (minus his first wife, who’d stayed home with the children). Sitting on a park bench one morning, he later told Janet, he’d struck up a conversation with an attractive married woman who was there with a small child. She invited him back to her nearby apartment, fed him an elegant lunch, then took him to bed. “He told the story as if remembering a pleasant dream,” recalls Malcolm, who then veers abruptly into an account of Freudian dream interpretation, which dictates that the most trivial details, often or seemingly unrelated to the dream being related, invariably yield the key to its meaning. Might Botsford, who’d fought on the front lines in France and Germany and been part of a platoon that liberated a Nazi camp, have deployed the delightful story of his encounter in the park as “a homeopathic counter-narrative” to the traumas he’d experienced in the war, wonders Malcolm, hurling her deceased husband onto the couch for a bout of wild analysis.

So many narratives and counter-narratives, all so filigreed with feints and deflections. So many husbands and wives, so many lovers.

Matters are hardly cleared up by another little cherry bomb of a confession, once again featuring Gardner, in the book’s final entry, “A Work of Art.” The story goes like this. For many years Gardner had kept on his desk a particularly unskillful black-and-white snapshot of a man and a woman, backs to the camera, striding across a tennis court. Janet assumed these were friends but eventually learns it was a random photo Gardner had somewhere found and saved, for reasons he doesn’t know. In 1980, when Malcolm was selecting stills for Diana & Nikon, her essay collection on photographic aesthetics, as a sort of joke she’d included this found photo among the “real” snapshot-style photographs by the likes of Robert Frank and Joel Meyerowitz, labeling it “G. Botsford, Untitled, 1971.” “The temptation was too great,” she semi-explains. “As if this wasn’t enough wicked joy for a single lifetime,” the Botsford photo was regarded as so unquestionably genuine that it was reproduced, four years later, in a critical study of the snapshot genre. “The reader may be wondering how this act of mischief could have gone undetected,” gloats Malcolm, concluding with the hope that G. Botsford’s Untitled will someday assume its place in an important collection, and—in her final published words to date—“I will take up mine in the annals of horsing around.”

If Malcolm occasionally enjoyed putting things over on her readers, are we meant to be on alert for further mischief from the grave? I find the prospect cheering, though it also brought me back to “The Apartment.” Something nagged me about it, from the title’s homage to Billy Wilder’s film of the same name (also about adultery), to the rented apartment so reminiscent of Harold Pinter’s Betrayal (also about a publishing-world triangle), and of course Botsford’s gauzy Parisian “memory” (or was it a dream?), which reads as if lifted from the pages of, I don’t know, James Salter?

Maybe all adultery stories have an already-told quality. I suspect Malcolm’s own general feeling was that people’s stories about themselves are invariably a little canned. Needless to say, if you start with the premise that self-deception is the bedrock of human psychology and just let your subjects keep talking, you’ll invariably be proven correct, as she so often was. She patiently waited until the evidence was in hand, and in her hands, everything was evidence.

However actual events played out, one gathers that the emotional truth of “The Apartment” was lodged elsewhere than within those apartment walls. Malcolm suggests as much herself in a 2013 interview—which took place, unusually, over lunch (Malcolm usually insisted on answering interview questions via email)—with the British journalist Gaby Wood. Wood asks whether Malcolm had ever felt guilty toward her interview subjects. Malcolm responds instead—maybe there was wine at lunch?—about her lingering guilt over Donald’s illnesses, and the unnecessary surgeries he’d undergone. Puzzled, Wood asks if there was cause for guilt there. “Well, there always is. I don’t know if there always is, but . . . maybe you shouldn’t put any of that in your article,” Malcolm stammers (you see why she preferred email interviews), adding: “Well, I don’t know. I’m not going to tell you what to write. It was very complex, and I guess private, somehow, at this point.”

Private, and in some lacerating way, apparently unresolved to the end. I recalled Shawn’s stirring sentences about Donald having been thrown back on himself, his life contracted to one room, which now read like a sub-rosa rebuke. At least I’d read it that way if it were my lonely dead husband under discussion. The revered Mr. Shawn had managed his own amorous life very differently, refusing to leave his wife when she wouldn’t give him a divorce, and conducting a forty-year quasi-marriage with another woman, while never entirely moving out of the family home. (His wife knew everything, Lillian Ross revealed in Here but Not Here, her 1988 memoir about the arrangement.) Might the different moral calculations made by his similarly situated colleagues have been somewhere in the back of Shawn’s mind when he penned that elegantly knife-twisting tribute to Donald?

I would have loved to have heard more from Malcolm herself on the calibrated hide-and-seek of “The Apartment.” She’s obviously entitled to however much “cowardly withholding” she chooses to exercise, it’s the announcing of it that seems coquettish: you feel like you’re being simultaneously beckoned to follow and thrown off the trail. Faced with similar rhetorical bait, I suspect Malcolm would have been all over it like a psychoanalyst-bloodhound. No one had a lower threshold for coyness and circumlocution; no one teased more shreds of meaning from the unsaid said.

A final thought on unsaids—at least it’s something I’ve long wondered about and never seen anyone bring up. In the chapter titled “Sam Chwat” Malcolm writes about taking lessons from an acting coach in how to appear more relatable to a jury, as the retrial of Jeffrey Masson’s libel lawsuit against her loomed. (Masson had accused Malcolm of fabricating quotes—including of him saying he’d slept with a thousand women and was an “intellectual gigolo”—in an unflattering New Yorker profile; the jury found against her the first time around but deadlocked on damages. He lost at retrial.) The lawsuit is something Malcolm brings up a lot in passing. It nagged at her, understandably—she’d been accused of making things up, which stung. (And yet she admits to doing exactly that in “A Work of Art”—people really are baffling!)

Malcolm talks about the protracted legal battle—it dragged on for almost a decade—most fully in the afterword to her most well-known book, The Journalist and the Murderer, where she attempts to refute allegations that writing a book about another journalist accused of betraying his subject—Joe McGinnis, who’d been sued by convicted murderer Jeffrey MacDonald over McGinnis’s book Fatal Vision—was some sort of “covert confession” regarding Masson’s libel suit against her. (Malcolm basically eviscerates McGinnis and leaves him in a writhing heap, whether or not that counts as a covert confession.)

I’ve read this afterword many times, never without the thought that it strikes an embarrassingly defensive note. In “Sam Chwat” Malcolm admits—yet another late-life confession—that she’d been guilty, in that afterword, of trying to show off what a good writer she was, and thus had taken way too detached a tone. But something else goes unsaid, which has always left me incredulous: any mention of the bizarre accumulation of so many J’s and so many M’s in this convoluted story. We have J. Malcolm herself and J. Malcolm’s brilliant title, The J and the M; we have J. Malcolm’s satyromaniacal tormenter—one J. Masson—along with the two subsidiary J.M.s, MacDonald and McGinnis, with their respective guilty crimes. Did Malcolm herself never notice this? How could she not? It leaves me convinced that there are no coincidences of subject matter and writers are fated to bleed meaning from every pore, flinging clues about themselves around as haphazardly as the fugitive orangutan in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue.”

Then again, Malcolm wishing to claim her final resting place in “the annals of horsing around” for pulling off the found photo prank does leave me wondering how much other mischief she planted in plain sight, then had a secret chortle over.

Laura Kipnis is the author, most recently, of Love in the Time of Contagion: A Diagnosis (Pantheon, 2022).