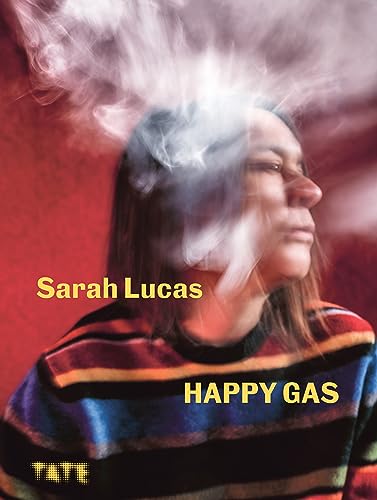

ARE WE ALLOWED TO ENJOY THIS? Chicks and dicks, fags and chicken thighs? Sarah Lucas’s sculptures use corner-store staples—bananas, cigarettes, a cucumber or two—to usher frisky innuendo into staid institutions. In the foreword to HAPPY GAS, a new book accompanying Lucas’s massive London retrospective, Alex Farquharson, the director of Tate Britain, writes: “Binary gender differences are exaggerated to the point of absurdity—no artists’ oeuvre is as populated with penises and breasts—then transgressed and undermined.”

Lucas doesn’t always expose her subjects in flagrante—the act itself is left to the viewer’s own dirty mind. Her 1994 work Au Naturel focuses on foreplay, freely mixing the squalid, the erotic, and the ridiculous. Two melons hang like breasts on the top portion of a stained yellow mattress folded against a wall. There is an overturned bucket beneath the melons and, on the right side of the makeshift bed, an erect cucumber with two oranges tight to the green phallus. Abrupt and vicious, Lucas’s work carries a direct carnal charge. (It reminds me of that famous Christian Grey quote, “I don’t make love. I fuck. Hard.”)

Lucas got her start in the late 1980s and early ’90s as one of the heralded YBAs (Young British Artists). Inflammatory art by Lucas and the likes of Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin made good copy for a public eager to be scandalized. After discovering Andrea Dworkin, Lucas began to display enlarged tabloid imagery on hallowed gallery walls. The cocks on chairs and fruity fuckers followed. People portrayed as food seem disposable—men are things that rot, cuckolds in their puny splendor. She likes to have her audience by the balls.

Butch sex appeal has always been integral to Lucas’s mythology. But she is not merely turning the phallus in on itself. As Amy Emmerson Martin points out in her essay—one of four in this crisp volume—the artist returns our lewd gaze, rearranging the very act of visual pleasure. Her early self-portraits look macho, but, as Lucas told curator James Putnam on the occasion of a show at the Freud Museum London in 2000, “I don’t think I consciously intended to look masculine.” Playing with gender was a way of confronting the male-dominated working-class world she grew up in. Masculinity allowed her mobility. In the exhibition at the good doctor’s onetime home in London, florescent lights penetrated couches, and hysterical eyes monitored Freud’s bedroom and study. The woman on the couch fights back.

FAT DORIS, 2023, is a sagging woman with dull tights, muddy brown heels, and two drooping eyelike knockers sitting on a purple argyle armchair. Stately women who were often overlooked become royalty. CROSS DORIS, 2019, and TITTIPUSSIDAD, 2018, are similarly saggy but made in bronze, silkily wrapped across their chairs. This is a far cry from the working-class women Nathalie Olah praises Lucas for depicting in her essay “Lumpy.” Instead of a struggling everywoman and her classic hangover breakfast, the later work crowns the arrival of a queen.