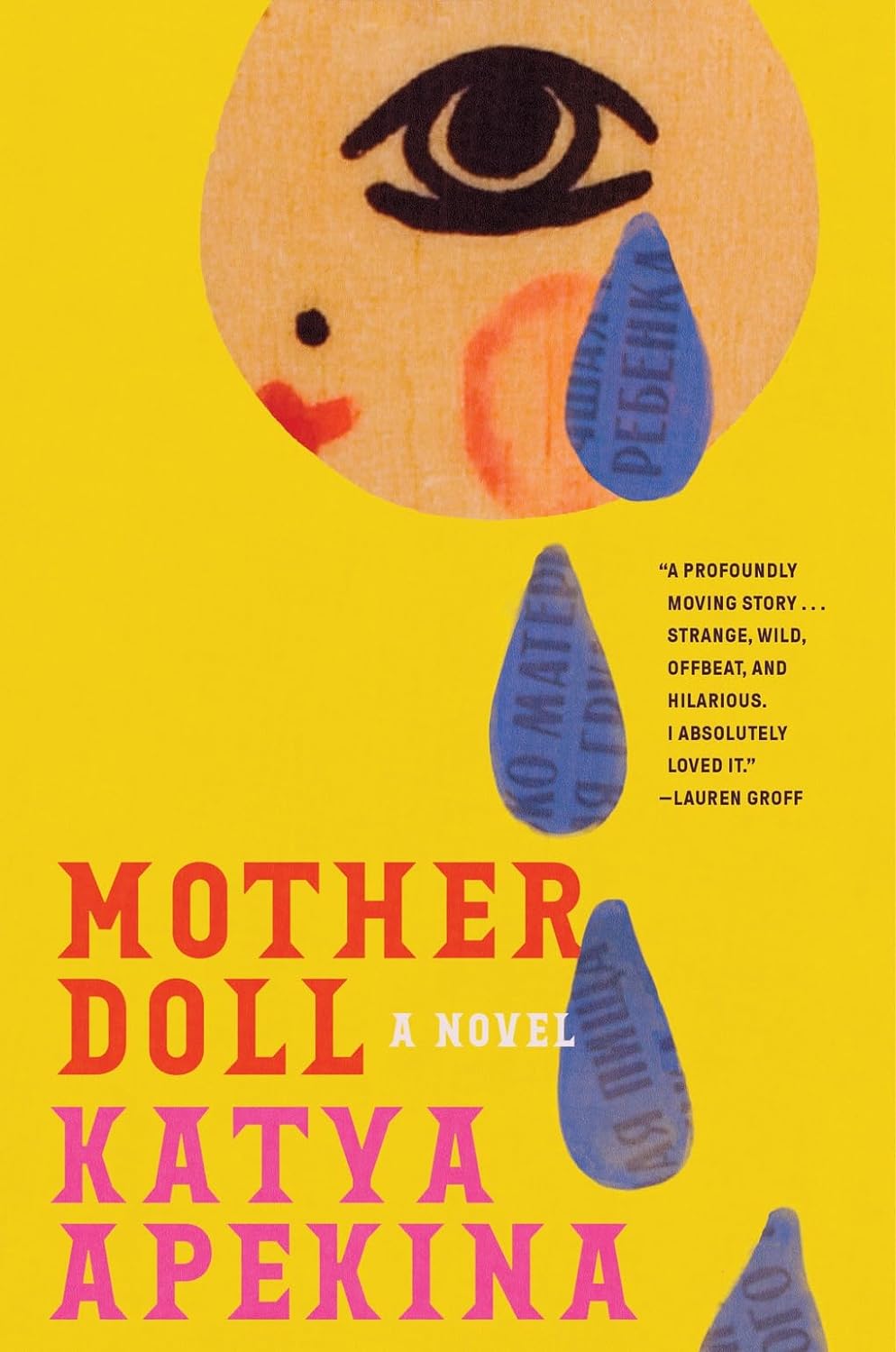

WHILE READING KATYA APEKINA’S spellbinding sophomore novel, Mother Doll, I kept wondering who its protagonist, Irina Petrova, the feisty, over-the-top spirit of a deceased Russian revolutionary, reminded me of. I searched for a literary precursor before it occurred to me that she had evoked the disruptive ghost Fruma-Sarah from the film Fiddler on the Roof. The movie’s jealous spirit doesn’t manifest through a visitation but rather a dream the protagonist conjures up in order to withdraw his daughter from an arranged marriage. In the book, the threat of the unsettled dead works toward positive ends. But not always: Irina Petrova, who appears through an apprehensive medium, Paul Zelmont, is devastating. She haunts three generations of women, and before she departs Paul’s body, she disables him with a stroke. He will never channel another spirit again.

Mother Doll opens with Ben and Zhenia, a contemporary Los Angeles couple celebrating their childlessness after spending an evening with friends preoccupied with putting their newborn to bed. Ben and Zhenia imagine themselves free of the biological imperative to reproduce and are grateful not to have the responsibility of progeny. Their relief is short-lived. Zhenia soon discovers she’s pregnant, and maybe not so in love with her husband. The novel then radically transforms into an intergenerational drama with childbirth and child-rearing as its primary concerns. While there are some richly drawn male characters, the book ultimately focuses on the intimacies and betrayals of women. Don’t expect these characters to adhere to “girl code.” Their loyalties can be downright messy. They won’t tell their best friend that her partner is a philanderer, and often enough, they’re entangled in the affair.

The novel focuses on two love triangles. In present-day LA, there is Zhenia; Anton (who is her boss); and Anton’s wife, Chloe. In Petrograd during the Russian Revolution, we have Zhenia’s great-grandmother Irina; her husband, Osip, a committed Bolshevik; and Lara, a hunchbacked daughter of aristocrats whom Osip is in love with. The book’s direct channel runs between the long-deceased Irina and the pregnant Zhenia.

As the revolution takes hold, Irina is forced to leave her four-year-old daughter Vera Ospinova in an orphanage. That trauma echoes across generations. In Mother Doll, the pain of abandonment requires that no one be abandoned, so the dead remain, “a cloud of ancestral grief” jostling for attention in the present. Their voices bicker too much to function as a Greek chorus; instead, as Apekina writes, ancestors hang around “like bored people on a train who have all been crammed together for too long.”

Their stories, combining past and present, and ranging from grand historical event to chamber drama, bring to mind Tony Kushner’s expansive plays, and like his work, Apekina’s novel is spiked with wicked dialogue that moves rapidly from humor to dark pathos. In a monologue from Slavs!, Kushner writes that the Communist Party promised a different kind of history wherein each person, endowed with the divine, is an occupant “of a great chiming spaciousness that is not distance but time, time which never moves nor passes.” Mother Doll treats time and history similarly. It’s a novel in which the dead have a lot to say, and the living are in their thrall. The problem with the dead is that they lack boundaries and have little politesse.

Here’s an example of Irina’s Aunt Gittel cursing Irina after her daughter Hanna dies in a revolutionary act that Irina has helped to pull off:

“You should have stones and not children.” . . . “You should crap blood and pus.” “You should be transformed into a chandelier, to hang by day and to burn by night.” “All your teeth shall fall out but one to make you suffer.” “May the leeches drink you dry.” “May all ten plagues be visited upon you, one by one.” “It should have been you, not her. You.”

And Aunt Gittel happens to be one of the kinder characters in the novel!

ZHENIA’S ROCKY MARRIAGE to Ben comes to a head when they’re invited to a night out at the Hollywood Hills members-only club the Magic Castle. In one of the novel’s many exquisitely rendered scenes, they move from room to room, watching magic tricks that summon forth the married couple’s conflicts. When one of the entertainers approaches Zhenia, she asks if he can make things disappear. “Depends on the things,” the man says. Ben asks him, “Pregnancies?” Which leads Zhenia to reflect: she “had chosen to marry a person whom she held at arm’s length, whom she herself did not love, and maybe in all the upheaval of her childhood, she had not learned how to love or what that even meant.”

It may not be love, but rather marriage, that causes the greatest conflict for Zhenia. She’s having an affair with her boss, Anton, a relationship with consequences she only casually considers: “Infidelity was complicated, and frankly not something they’d discussed directly. It’s possible it wasn’t infidelity exactly.” Zhenia flirts via text with Anton, an ardent but cautious suitor who sends her a surreptitious dick pic “taken under a blanket—an outline of something in the dark.” Indeed, the novel takes a certain pleasure in its depiction of characters hiding transgressions both from others and themselves.

When she’s served divorce papers at her office, Zhenia imagines she’s just won the Publishers Clearing House Sweepstakes. It’s at around this time that Anton offers to hire Zhenia to accompany his wife, Chloe, during her pregnancy, fearing Chloe may become depressed. The two women take prenatal yoga classes together, where their relationship deepens, not only around their pregnancies, but their humbly shared writing aspirations. Chloe was a former adjunct creative writing teacher in St. Louis, and Zhenia is now deeply engaged in “ghostwriting,” as it were, Irina’s story. Ben and Zhenia, meanwhile, split the caretaking obligations of their newborn.

There’s something peculiar and yet inevitable about Zhenia and Chloe’s relationship, depicted here with tenderness even as Zhenia’s evasiveness borders on cruelty. As Zhenia begins to spend more time with Anton and Chloe than she does at home, she wonders, “Did she know about the hookups and their texts?” Later, she adds:

The truth was that Zhenia wasn’t sure how much Chloe knew. She didn’t know whether she and Chloe lived in a shared reality or not, and she was too scared to talk to her about it in case they didn’t. What if Chloe didn’t know about Zhenia and Anton at all, and what if it was something that would cause her pain? The arrangement was fragile and precious to Zhenia, and she didn’t want to lose it by defining things and realizing that maybe all of it had been a misunderstanding. Zhenia vaguely knew that she left a trail of destruction in her own wake, but to admit this was somehow lending herself a level of agency and power over other people she didn’t really believe she had.

It’s a tricky place to occupy—both the third wheel and the hub in a relationship no one wants to name. Yet Apekina convinces the reader that erotic attachment, like the unconscious, can’t be entirely articulated, and is, in itself, a kind of dreamy possession: “She was lying on her back, fully clothed, and Anton was lying beside her, head propped on his hand, looking at her face. He began to slowly unbutton her shirt with one hand. There were so many buttons, this went on forever.”

IRINA’S LOVE STORY comes at an opportune moment for Zhenia, acting as a mirror of her own affair. Apekina’s storytelling is at its finest in depicting Irina’s narrative. The arrival of Rasputin should be a cliché, but his appearance in Mother Doll is indelible. Here, Apekina again describes people’s ability to overlook just about anything in deference to power:

The man who came in stank like a goat. . . . He’d opened all the birdcages in the other room, and now the little canaries were flying in desperate circles around the dining room. One flew right into the window behind me. Another was perched on this man’s shoulder, edging its way toward his beard, which was thick and long and seemed to contain food. . . . Rasputin was flanked by an entourage, some dressed like him in peasant clothes, others in elegant suits. Bird shit was landing periodically on the tablecloth, which everyone was pretending was not unusual in the least.

Irina narrates her life, including her years at a finishing school. Here, the narrative briefly turns into an espionage thriller. Through her governess’s connection to a Russian general, Irina, her cousin Hanna, and their friend Olga enter a world of intellectuals and agitators. Eventually the girls are sent on a mission to help a man escape prison (they deliver him a gun and bullets), and later to bomb the very general who’d gotten their teacher her job. The girls’ exploits are vivid, as Nabokovian as Kinbote’s escape from Zembla. And as the revolution unfolds and hunger and cold pervade Petrograd, Apekina’s descriptive powers sharpen, as do the circumstances that fuel Irina’s choices. We expect to find desperation or passion in a civilian’s transformation to a terrorist. But Irina is merely determined. She admits to a “primitive” politics: “I was aligned with the Bolsheviks, but I did not like the way they presented themselves aesthetically. . . . Nor did I romanticize factory workers, and even less so, peasants.”

Irina’s transformation does not derive from an inflamed commitment but rather a cool rigidity: “We had already decided that we were the kind of people who did this and so we became the kind of people who did this and so we did this.” Her passions are reserved for Osip, but also for his lover of over a decade, Lara. The throuple are at times depicted as almost blissful, and yet Irina can never quite hide her vindictive streak. She sleeps between them, adopting them as a mother and father. And Lara supports them by stealing from her aristocratic family who pity her, both for her hump, and the surgeries they subjected her to, including a sterilization when they feared she would not be able to carry a child. During the time of the Provisional Government, when Irina and Lara have to pull up the floorboards to use as kindling, Lara’s family begs her to leave for Paris with them, insisting Osip will never marry her. But, in fact, Irina has already married Osip. The union was Lara’s idea because she feared that Irina would be shipped off for not having papers. These delayed disclosures and reversals contribute to the novel’s intricate game of loyalties, keeping the reader’s sympathies for the characters in flux. What’s remarkable is how much we end up feeling for all of them.

Apekina’s characters, like the Revolution unfolding around them, are compromised, reckless, full of commitments and desires they cannot realize. And yet it’s ultimately compromise that saves them. On her wedding day, Irina wears one of Lara’s tailored dresses. It’s a perfect example of how the novel can make a kind gesture appear painful. In a charged scene that sums up the throuple’s bizarre dynamic, Irina follows Osip into the bathroom. When he cuts himself shaving, Irina licks the blood from his cheek as Lara looks on. It’s hard to read this as anything but a callous provocation, a moment in which she announces, “I won.” But Irina, like Zhenia, has a powerful rationalization:

I wanted to get rid of her by then—so that Osip and I could have a true romance, not controlled by her and not squeezed into the sanctioned corners. But the relationship Osip and I had, it required a lot of external buttressing. All those other people had seemed like inconveniences and breaks to our passion, but really they were structurally necessary, and when all those limitations were gone, and we were free to do as we wanted, like when we went to Switzerland, things did not go well for us at all.

There is something socialist in acknowledging that our relationships require buttressing, that families, even lineages, are collaboratives. And in Mother Doll, despite the often-casual cruelties, both Zhenia and Irina merge, literally and metaphorically, with this common lesson. It’s almost gratifying, then, to see Zhenia taken in by Anton and Chloe, configuring for themselves a family unit only they can consent to, and for which they need not apologize.

Adam Klein is the author of the novel Tiny Ladies (Dzanc, 2014).