“I’M NOT EVEN INTERESTED IN MOMENTS.” The German photographer Evelyn Hofer (1922–2009) knew her aesthetic was in some ways at odds with her time; her postwar streets and squares are emphatically not in the style of Henri Cartier-Bresson and his influential “decisive moment” or the street photographers who followed his example: William Klein, Garry Winogrand, Helen Levitt, and so many more. In six books devoted to cities, and another to Spain, Hofer adhered to a monumental, frontal, and large-format style that owes more to Eugène Atget and August Sander. Working with Mary McCarthy on The Stones of Florence (1959), Hofer complained that the writer behaved like a Victorian lady looking for picturesque snapshots and colorful folk. Hofer instead framed an unpeopled city that had “nothing to do with our times”—an approach that today has the curious effect of making some of her series resemble later, more critically minded or even Conceptual photography: the New Topographics artists in the mid-1970s like Robert Adams and Lewis Baltz or Thomas Struth’s empty New York streets toward the end of that decade, among others from the Düsseldorf School.

Dublin in the ’60s was not a natural subject for Hofer. Civic buildings remained blackened by diesel fumes and coal-fire smoke, Georgian terraces were dilapidated or being torn down, and Dubliners were altogether less timeless in aspect than their rural relatives. V. S. Pritchett, commissioned to write the text for Dublin: A Portrait (1967), had told her it was one of the most beautiful cities in Europe, but Hofer was dismayed: “There is no space—and I cannot show [the buildings] to their advantage.” Pritchett had reported from Ireland during the country’s Civil War and remembered a capital torn between commerce and revolution. Like Rocky Road to Dublin, Peter Lennon’s mordant documentary of 1968, Hofer’s photographs show a postrevolutionary city darkened by poverty and muted by piety. Here are rawboned seminarians on their bicycles, and orphanage beds crammed together in front of a chapel altar under the chilly gaze of the Virgin.

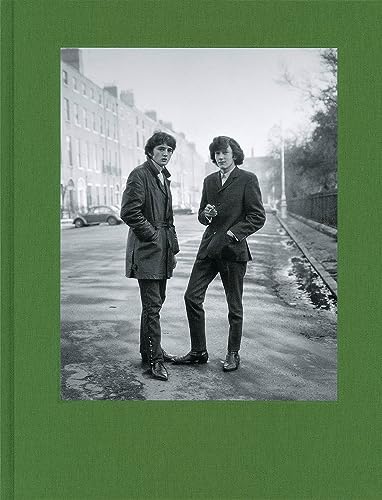

A new edition of Hofer’s book, titled simply Dublin, was announced some years ago by Steidl and has finally arrived, following a survey of Hofer’s work at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City and at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta. It is a shame to lose Pritchett’s period text (would a publisher have done the same to McCarthy?), but a new essay by the novelist Hugo Hamilton encourages us to see fresh and less hidebound things in Hofer’s seemingly austere classicism. The promise of another Dublin—the one I grew up in, as it happens—may be found in the pointed boots and dandy stances (but still awkward hair) of two young mods in Fitzwilliam Square. There is pure mischief in the faces of a group of schoolkids who will not stay still, and a different revolution stirring in the expressions of certain women, including the writer Mary Lavin. For me, Hofer’s greatest photograph is her color study of a young girl on a too-large bicycle, at the empty junction of redbrick streets in the Liberties, a working-class district close to the center. In the new edition, alternate versions show how hard Hofer worked to isolate her subject—all that empty space denoting sheer potential.