CONSTANCE DEBRÉ’S autobiographical novel Playboy is the story of a metamorphosis. We meet the narrator just after she has left her husband, Laurent, and started dating and having sex with women. She had been with Laurent for fifteen years. They were both bored the entire time. The boredom was “a solid foundation,” “a bomb shelter.”

The essence of couple life is being bored shitless. Couple life and life in general. In that sense, we were compatible, Laurent and I. . . . We were both the same height, we wore the same clothes, we were both as bored as each other. . . . What we liked doing was waking up together every morning and saying How is it possible to be this fucking bored? We thought it was funny. It worked pretty well.

She might have stayed bored with Laurent forever, she writes, if she hadn’t had their son, Paul. She bridled under everyone’s “sentimental bullshit” about motherhood. She didn’t like spending so much time shopping and preparing food. “There was no more space for emptiness.” After leaving Laurent she throws away all her stuff. She keeps two pairs of jeans and a jacket and a bed for Paul when he’s there. (She sleeps on a couch.) Desire for women consumes her and converts her. It turns her into a writer. I don’t mean that it gives her “material.” It’s like she meets Rilke’s torso of Apollo, and, reborn by the curved breast, must change her life.

Like Debré herself, the narrator is trained as a defense attorney. “I like the guilty parties, the pedophiles, thieves, rapists, armed robbers, murderers,” she writes. “It’s innocent people and victims I don’t know how to defend.” What interests her about her clients is not the fact of their guilt (she never imagines that they haven’t done something wrong). “It’s seeing how low a man can stoop. . . . It takes a special kind of courage to get that low.” Eventually she quits her job and begins writing the book we are reading, which tracks her attempt to, in a certain sense, get low. She sheds everything most people spend their lives trying to acquire—possessions, security, comforts. Her temper is as caustic as detergent. She hates other parents, how concerned they are with home renovations and summer plans. “People get scared by the slightest thing,” she writes. “I get bored by the slightest thing. That’s the difference between them and me.” Some things do scare her. Chapter 23 of Playboy reads, in its entirety:

I’m so scared of not being able to come. It’s terrifying how much it terrifies me. I don’t know what I’d do with the emptiness. That’s why you have to be tough, you have to keep your body strong. To get through the fear. Fear of desire, fear of love, all the fears. Then everything will be OK.

The word “playboy” in English conjures up images of expensive liquor, fancy clothes, mansions, etc. But Debré is more focused. Her “never-ending desire” is for women, and writing about them. Things begin clumsily. An affair with Agnès, a married woman ten years older, builds slowly. There are walks in the Jardin des Plantes, fumbling almost-touches, embraces that go on too long but don’t build to more. The narrator loves Agnès, though she doesn’t much like her, and is embarrassed by her in public. Eventually she realizes that she has to be the one to bring matters to a head. Debré’s voice is like a diamond drill boring through stone. “The thought scared me. I liked it, too. I liked the idea of being the boy.”

Desire, as it usually does, curdles. Agnès is a selfish lover; the narrator gives more than she gets. But disgust is more of an issue outside the bedroom. Agnès “arrives early, she wants to have dinner right away. Eating is important to her.” The narrator makes her pasta and doesn’t eat any herself; she smokes instead. She rarely cooks. Usually she gets by on sandwiches from Così and Japanese takeout, or veggie patties, which she eats cold, with ketchup. She goes out for dinner a lot but doesn’t seem to care about how things taste. With one exception, naturally: “A cunt is made for a face to go down on . . . that fucking sweet taste.”

Writing explicitly about sex is provocative. Being too interested in food would be tacky, domestic. Debré’s narrator is comfortable with the upper classes and the down-and-out—“when your parents are upper-class junkies, you get good training”—but with Agnès has her first experience of a member of the “petty bourgeoisie.” She’s cast off the comforts of her class position, but she’s still rich on the inside. She tries to get used to Agnès’s mannerisms—the phrases like “Oh shoot” and “the little ones,” the habit of taking one’s shoes off at the door—and can’t. She admits to speaking with a “snobby accent.” She’s related to duchesses on her mother’s side; her grandfather on her father’s side was the prime minister. (Debré doesn’t spell it out, but the reference is to Michel Debré, who held office for three years under de Gaulle, and drafted the Constitution of the Fifth Republic.) She loves filthy language, and bourgeois striving and planning make no sense to her. She lives cheaply and insists that her change of station involves real risk, casting aspersion on the middle-class assumption that “when your family name’s in the dictionary you must automatically have money invested in mutual funds.” She writes that making money “stresses me out,” that “it’s only when I’m poor and the bailiffs are on my ass that I feel like I’m where I belong.” She seeks extremity. But no bailiff actually comes to call. She’s “so rich that I don’t care about being poor.” One has to assume that, mutual funds aside, there must be some other account she is drawing down. Her descent in the world is an adventure, an existential victory. Being an outsider is a matter of principle, and it also happens to be less tacky than being middle-class.

There can be no separating the author’s family name from her public persona, or from her narrator’s experience. But despite giving us all the autobiographical details, Debré does not actually name her narrator. Perhaps this is a form of disavowal or repudiation. Or it could be that while going by another name would feel needlessly coy, using her own name would make it too easy for readers to forget the difference between a character and an author, a book and a life. Still, I’m tired of calling her “the narrator” over and over; from now on I’m going to call her “D.”

D.’s sexual odyssey takes her from Agnès to a “girl” named Albert fifteen years younger. They have “mind-blowing” sex for several chapters until D. loses interest. In the last chapter of Playboy, she’s sleeping with someone new and is “getting a little bored again. The problem is that even with girls, it’s all become banal.” That’s one arc. The other concerns her relationship with her father, who is cared for by an eighty-five-year-old aide. D. complains about him, but she cares enough to confront him, to force him to know her; it’s a relationship in flux, which makes it interesting. The third arc is about Paul. She comes to think of herself as Paul’s father, rather than his mother: “fathers have no fear, they don’t have this need to be loved by their children, so they leave them the fuck alone and let them grow up.” When Paul is hostile to her, she is understanding: “maybe he’s decided to hate me to make his dad happy.” She divides hate and love between her father and her son, protecting one and flaying the other, but demonstrating deep, pained attachments to both.

Laurent starts keeping Paul away from her, “collecting evidence” that she is “dangerous” to use against her in court. Paul doesn’t always want to see her. A child psychologist asks her if she loves Paul. “I looked at her red Lancel bag and her Hermès watch with the double strap and told myself it wasn’t even worth answering.”

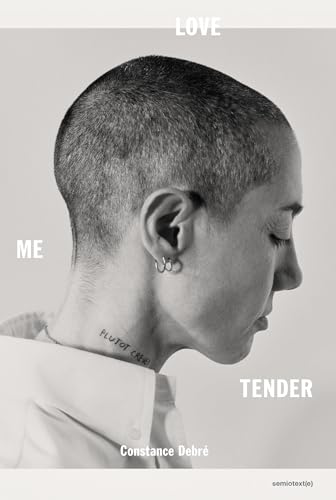

PLAYBOY IS THE FIRST in a trilogy, but the second to be published in the United States; Love Me Tender, the second volume, came out here two years ago. Where Playboy is tough and sexy, Love Me Tender is devastating. Laurent files a court order accusing D. of incest and pedophilia, “directly or through involvement of a third party.” As evidence, he submits a list of books that D. owns by Georges Bataille, Tony Duvert, and Hervé Guibert. At the hearing, his lawyer reads passages of Guibert’s Crazy for Vincent out loud. The judge wants to know what the book D. is writing is about. The book tracks the maneuvers that keep mother and son apart.

Flattened in the wringer of bureaucratic absurdity, ground up in the violence of the law, D. maintains her cool. She compares herself to Socrates, Jesus, Oscar Wilde, and Spinoza. “No great life is complete without a trial, you have to ruffle a few feathers, you can’t just be a good little child all your life.” She’s flip; incest was not a crime she had ever imagined committing. “It’s such a rich crime. . . . A real man’s crime. Almost a mark of recognition for a woman.” She waits months for psychological evaluations, and eventually earns the right for supervised visits. Sometimes Paul doesn’t show up; other times he says he doesn’t want to see her. D. remains at once passionately devoted and indifferent. She treats her son with respect, not solicitude. She holds the pain of separation at arm’s length—not denying it, but not describing it, either. This pain is the void that her life is organized around. By the end of the novel, D. has stopped going to Laurent’s to pick Paul up. They text sometimes. “Sometimes he replies, sometimes he doesn’t.” The “sadness”—a sadness all the bleaker and deeper for never being opened to the reader—“is gone.”

In Love Me Tender, D. tells the story of awakening to her desire for women a little differently than she did in Playboy. In Playboy, it was about rebelling against the cage of sentimental motherhood and domesticity. In Love Me Tender, she writes that the honesty of her relationship with her son pushed or required her to be honest with herself. “I might never have become a lesbian if I hadn’t been his mother first.” Her gratitude, if that’s what it is, is as pitiless as her grief.

D. CHANGES IN SIGNIFICANT WAYS over the course of these novels. Her taste in literature: “I didn’t understand why Proust and all the others had been so important to me.” Her body: swimming every day makes her strong and muscular. She gets tattoos (a pinup on one shoulder, a trail of ink down one arm) and an earring, cuts her hair short. She grows sexually confident, even swaggering. The pursuit of sex goes from rapturous to cynical to compulsive. “People who fuck a lot aren’t doing it for fun,” she writes in Love Me Tender. She compares herself to “a teenager in front of a PlayStation, giving myself brain damage from playing too much Call of Duty, a teenager that might just end up hanging himself in his room, killing half his class, or, just as likely, doing nothing at all.” She can’t stand the expectations of romance. She doesn’t want to hold hands, talk about nice restaurants, go on vacation, talk about jobs. She didn’t change her life in order to rebuild it the same way, swapping a husband for a wife. “I did it for a new life, for the adventure.” She writes, “I wish I could’ve been a fag.” But even as she changes, growing more disciplined and lonesome, more fearless and convicted, her voice persists. She has a lawyerly appreciation of the facts. But she’s funny, too, as when she describes herself as “a cross between the Baron de Charlus and Sid Vicious.”

There’s no agony or confusion around her sexuality. She isn’t interested in bemoaning how or why she lived so long as a straight woman. She doesn’t use the language of the closet or repression. She’s been converted, yes, and everything is different, but everything is also the same; she doesn’t dwell on the moment of revelation; it seems like there wasn’t one. As a child, she was a tomboy who preferred boys’ clothes and toys. “At the age of four I was a homosexual. I knew full well and so did my parents. After that it kind of passed. Now it’s coming back. It’s as simple as that.”

Part of this narrator’s appeal is how simple she makes things, especially in Playboy. Almost everything for her is simple, or easy. It was easy to act feminine for men; now it’s easy to pick out the girl who will sleep with you. It’s easy to get back together with Agnès, and it’s easy to love her less. (She saves the word “hard” for describing her swimmer’s body, or the intensity with which Albert comes.) Love Me Tender acknowledges more difficulty, but the language is not any more embellished. She addresses Paul: “It’s going to be OK, you know. Even if it’s hard.” The agony of thought that is the focus of so much literature has no place here.

In interviews, Debré cites Guillaume Dustan as an influence. (Dustan also came from the world of law; he was an administrative judge before he became a writer.) Like Dustan’s, her prose is free of metaphor and figurative language; she uses ordinary words to describe ordinary activities. The narrative is broken into small episodes that have a photographic quality. Most of the book narrates everyday action. And she shares Dustan’s sense that sex opens up possibility. But Debré is also philosophical: “I’m rich and she’s poor. That’s why I’m going to win. It’s inevitable.” Or: “There’s always a moment when you see their face, the face of a drowning person, the expression they’ll have when the time comes to die, all that despair.” Her interest is not solely in surfaces; she also stargazes from the gutter. But these jetsam of self-discovery are washed up from a sea of unknowable feeling and experience. It’s easy to get fooled by the simplicity and directness of the style, but there is nothing intimate about what she reveals. Withholding her own feelings, she gives the reader room to feel.

Some of the emptiness is attributable to her lack of interest in objects. Her idea of description is a phrase like “my ripped APC pants” or “battered red espadrilles and an old pair of jeans.” Objects have no histories in her world; nothing has been passed down or saved or imbued with meaning; the only attachments are those that language can make, a bond entered into for as long as it takes to read a sentence. The reader doesn’t see the world laid out; it’s not a visual text. A voice speaks. Debré writes at one point that she wants to “extricate” herself “from life” like one of her father’s old junkie friends. I don’t really believe her. What she wants, I think, is to maintain the slimmest, thinnest thread of a connection. To be a voice rather than a body, even as the voice lavishes attention on its desire for bodies.

Love Me Tender ends with D. and a new girlfriend, S., entertaining the idea of moving in together. “I’ve thought about it. There aren’t that many different solutions” is the last line of the book. It’s a disillusion as profound as that at the end of any plot of any bildung. Debré has paid a high price to turn her life into art. But after finishing the draft of Playboy, D. feels no regret. “Even with a gun to my head I wouldn’t have done anything differently.” In Nom, the third volume of the trilogy, which has not been published in the United States, Debré writes that her books “are not about telling my life” but about “explaining what has happened and how we should live.” I think she means that she cares less about identity than about actions and consequences. Still, I find Debré’s exquisite achievement not to reside in the realm of advice or guides for living. It’s in that cold sliver of voice, conducting electricity at a high voltage, sending the occasional shower of sparks off the page.

Christine Smallwood is the author of the novel The Life of the Mind (Hogarth, 2021) and the nonfiction book La Captive (Fireflies Press, 2024).