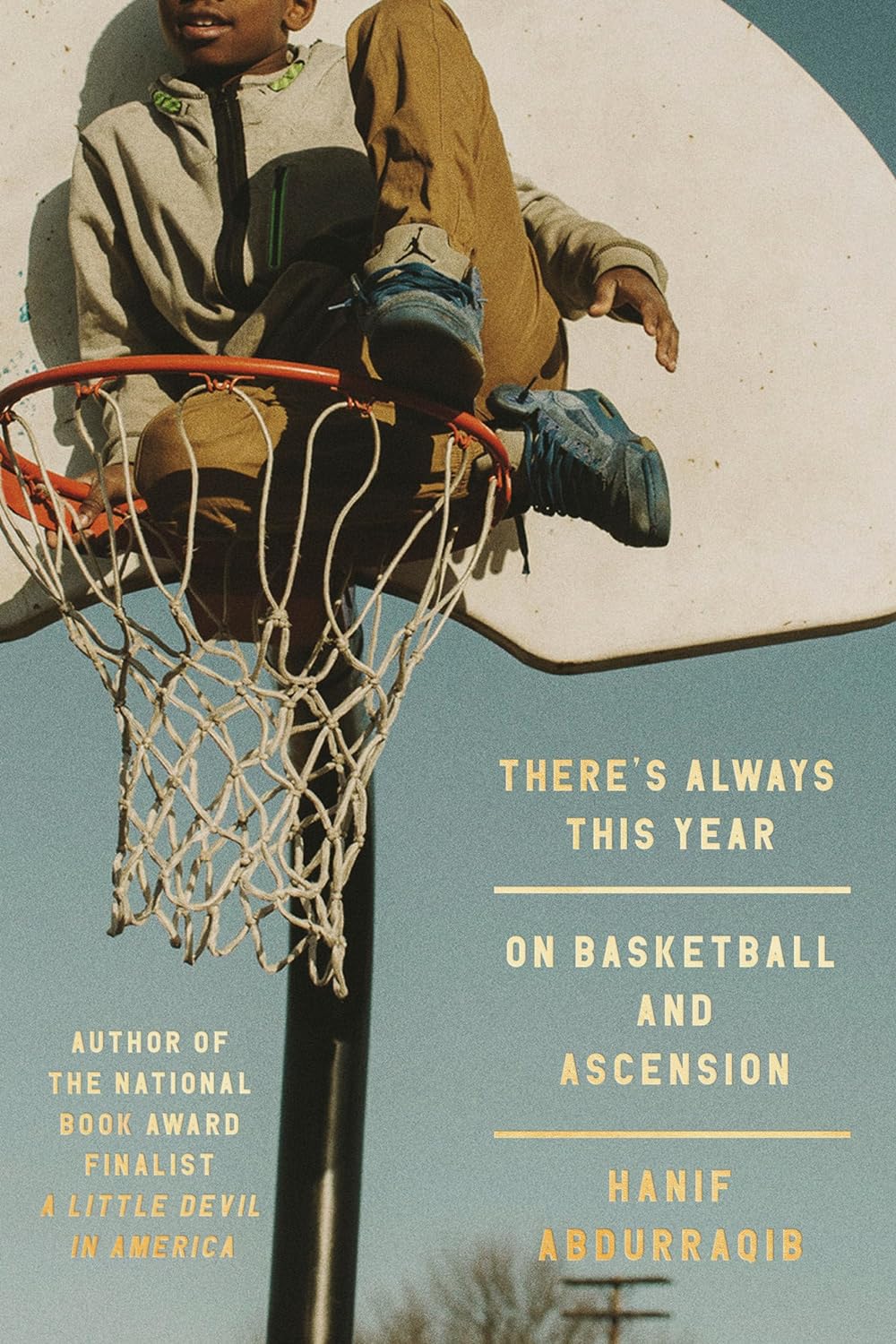

IN TODAY’S INSTALLMENT of “You’re Never Too Old to Learn,” it turns out that it’s not just its location that makes the state of Ohio the heartland of America. It’s also because, as its native son Hanif Abdurraqib writes in There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension, the seventeenth state of the Union is “shaped like a heart. A jagged heart. A heart with sharp edges. A heart as a weapon.” This disclosure, one in a torrent of observations, ruminations, and reveries tightly woven into the book’s narrative, gives you some idea of Abdurraqib’s willingness to pile everything he’s able into his quasi-autobiographical, proto-philosophical inquiry into turn-of-the-twenty-first-century basketball, especially its prodigiously gifted Ohio-bred avatar for both triumph and tribulation, LeBron James.

In this testament to both a sport and a state, Abdurraqib leads with his own heart, one that’s been broken over time by loss of family, friends, even a home. His previous works of cultural criticism (A Little Devil in America, Go Ahead in the Rain, They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us) and poetry (A Fortune for Your Disaster, The Crown Ain’t Worth Much) are steeped in elegy and tempered by irony. He goes all out to sustain this difficult balance in his newest and, one could argue, most ambitious solo performance thus far, an awesomely discursive mixtape of memoir, film criticism, tone poem, and sports punditry interspersed with brief tributes to “legendary Ohio aviators” in whose company he includes Lonnie Carmon, the Black Columbus junk collector who built a plane from some of his salvage and flew it on weekends to astonish and inspire his neighbors. Other Buckeye State heroes need little to no introduction to the rest of us: John Glenn and John Brown, Toni Morrison and Virginia Hamilton.

Though Abdurraqib doesn’t say so explicitly, those last two African American native daughters (Morrison was from Lorain and Hamilton was from Dayton, where, by the way, the Wright Brothers and Paul Lawrence Dunbar were well acquainted with one another) each wrote books declaring that Black people could, indeed, fly. Morrison’s novel Song of Solomon came out in 1977, by which time skywalkers like Julius Erving and David Thompson were exploding the parameters of mid-air acrobatics “within the paint” of a basketball court. And by the time Hamilton’s collection of folktales The People Could Fly was published in 1985, further affirmation of her title’s premise could be found in Michael Jordan’s otherworldly rookie season with the Chicago Bulls. It is with that season that Abdurraqib (appropriately) commences his inquiry; the beginning of Jordan’s incomparable career “when,” as Abdurraqib notes, “he hadn’t yet begun to take a blade to his scalp” and somehow lost that year’s all-star dunk contest while striking an indelible pose “soaring toward the basket, his arm cradling the rock with ill intentions, eyeing the rim like prey, like he’s already seen its demise.” It was upon this image that millions of expensive sneakers would be sold. Basketball’s profile was raised all over the planet, and dreams as big as other planets spawned and grew in generations of young athletes, the most promising of whom lived roughly 125 miles away from Abdurraqib’s hometown of Columbus: Akron’s LeBron James, described early on as “a 14-year-old, skinny and seemingly poured into an oversized basketball uniform that always suggested it was one quick move away from evicting him.”

Both James and his legend would grow exponentially from there. But as you’ve already surmised, There’s Always This Year is in no way a conventional biography or appreciation of one athlete’s career. It is more a portrait of Abdurraqib-the-artist as a young man, living his own tribulation-laden life through the last decade of the twentieth century and the first two of the twenty-first while taking in everything going on around him, even beyond the mean streets of Columbus. The author would eventually leave for New Haven, Connecticut, just as James would leave (his despondent-at-the-time fans would say “abandon”) Cleveland and “take [his] talents” to Miami.

The alignment of the author’s life with that of its guiding spirit is made evident throughout the book. But it isn’t seamless, and it isn’t supposed to be. There are many ways of looking at basketball and basketball players. Abdurraqib, in this spirit, submits the names of hoop legends to consider from his “jagged city” in the center of Ohio, such as Kenny Gregory, later a star for the University of Kansas Jayhawks, whose participation in the McDonald’s All-American Game for high schoolers “was the first time any of us could turn on ESPN and see a kid we’d fetched balls for in the park or hit up for corner store cash.” By contrast, there’s another local hero named Estaban Weaver, considered the most gifted young baller in Columbus history, who didn’t make the McDonald’s all-stars and dropped out of high school; whatever promise his talents augured trailed off into litanies of “what happened” and “what ifs.”

“The math of who makes it and who doesn’t, or what making it even is,” Abdurraqib writes. “All of it, a series of accidents.” Nevertheless, Abdurraqib rejects the temptation to make cheap melodrama of such outcomes: “Don’t talk to me about any version of making it that ends with someone like Estaban Weaver being described as a failure. . . . Not if you don’t know what it’s like for a city to make you into a savior before you finish ninth grade. Not if, despite that, you survived.”

Paraphrasing that talented teenage goalkeeper Albert Camus, the intellect, if it’s worth anything in its own fields of play, watches itself as intently and as unsparingly as it watches others. Maybe that’s why Abdurraqib’s book makes its most breathtaking pivots when he probes the act of bearing witness. While watching the fifth game of the 2007 NBA Eastern Conference Finals between the Cleveland Cavaliers and the Detroit Pistons, he and his friends behold LeBron James leading his Cavs to victory by scoring the final twenty-five points of the game by himself. “It was like entering a portal, going from one game to an entirely unique game, almost cartoonish in nature, a game in which there was LeBron James, maneuvering through five foes and emerging victorious in almost every possession.” In stark contrast to this seemingly miraculous turn of events, Abdurraqib is watching this in his “cramped one-bedroom apartment, right before eviction, where I hadn’t paid the rent for two months but managed to keep the lights on and the cable bill paid.” But, as Abdurraqib observes, the notion of “miraculous” carries its own capacity for deception:

Who or what can make someone believe anything that would be otherwise unbelievable? I have no money for rent, but something will come through. I go to bed hungry but will wake up in the morning, and something might fall in my lap to keep me full. A team is losing until it isn’t. Until an architect of the miraculous takes over a game, and the deception becomes real. This is really happening. All of the good you believed would arrive, suddenly has. All of the bad that is coming, certainly will.

When athletic triumph and commonplace travail intersect, it’s hard not to think of Frederick Exley’s harrowing, mordantly funny novel A Fan’s Notes (1968), in which Exley, using a doppelgänger of himself as protagonist, details his rueful encounters with mental illness, shock therapy, and alcoholism, all the while measuring his thwarted lunges at the American Dream throughout the 1950s against the seemingly effortless ascension of his more illustrious USC classmate and New York Giants star halfback Frank Gifford. But Abdurraqib is writing nonfiction that is at once as intimately confessional as Exley’s novel and far broader in social, cultural, and political reach than anyone from Exley’s “silent generation” would dare. The 2014 police shooting of Tamir Rice, a fixture of Ohio’s recent history as unavoidable as James’s return from Miami to Cleveland that same year, cast unsettling shadows on the latter parts of the book, as in this passage:

2:20

The spectacular isn’t all that unfolds in a matter of unstoppable seconds

there is more than a ball pirouetting through an arena’s sky navigating a course toward destiny have you considered how quickly a heart can stop

2:19

beating how quickly blood can sprint from a wound there is no clock that turns back so quickly that life might be gifted to the dead there is no resurrection from the panicked ticking that haunts the already-eager fingers on triggers and I am talking real triggers the bullet travels faster than the speed

2:18

of sound and so what to make then of the cop who pulls up in a car and maybe shouts but maybe doesn’t but definitely fires

2:17

a bullet that arrives before the sound of his voice what to make of this besides someone who wanted someone else dead someone who made up their mind who did not in doing so imagine the casket or the mother crying atop it

He is a poet. He is also, in this book, more formally audacious with prose than he’s ever been before. Abdurraqib divides his book-length essay into the four “quarters” that comprise a professional basketball game, each quarter set at the requisite twelve minutes and counting down (as demonstrated above) in subdivisions of minutes and seconds in what ballers and refs alike label “regulation time.” This narrative device allows him to contain and control the teeming flow of memories, ideas, analogies, and digressions. Sometimes, as in the above passage, the flow of word, image, and thought jukes, stutter-steps, reloads, and rushes headlong toward open space, jolting the reader in the same manner that a shooting guard executes a head fake on a defender so abrupt and violent as to be labeled by awestruck broadcasters as an “ankle breaker.”

Here he is with 11:11 left in the second quarter:

Tough for me to tell the difference between a prayer and a wish, though some might say a prayer is simply a wish that punches above its weight. A wish leaves the lips and depending on how it is spoken—its tone or the desire attached to it—it either gains wings or falls on the ears of the living.

There’s Always This Year is the kind of book that looks a lot easier to write than it actually must have been. All that’s required, it seems, is the willingness to play shoot-around with your past selves in the presence of your sports idol and let the platitudes about Overcoming and Uplift do the rest of the work. But life is not a pop anthem of uplift, and ankles aren’t the only things that get broken when neither your wishes nor your prayers get answered.

“As funny as it is to say,” Abdurraqib confesses at one point, “I don’t remember the exact reason I ended up handcuffed in the back of a cop car in the fall of 2004.” It’s one of several moments in the book when your assumptions about time and chronology get faked out. It’s not explained why or how he was arrested (“no telling what the warrant might have been for”). What matters is that when Abdurraqib was in the stir, waiting for his court date, LeBron James, from his higher position on life’s stage, was a work in progress, still trying to subdue the skeptics even after he’d been named NBA Rookie of the Year the season before. Abdurraqib sees James through the static of a jailhouse TV, giving an interview before the 2004–5 season. (“The minute he appeared on the screen, the loud and reckless debate unfurled” among Abdurraqib’s fellow inmates. “He ain’t shit, or he is. Cavs ain’t never gonna be shit, or they are.”) Another flashback, another pivot in chronology: Abdurraqib remembers the year before when he was picking up odd jobs with local credit agencies in Columbus, seeking escape from the drudgery and dread by decorating his cubicle with magazine pictures of LeBron, the prized rookie. “As one life begins to ascend, another begins its descent,” Abdurraqib observes of this period in their shared existence. “It happens to everyone, everywhere, even if you don’t know the person who is watching your rise from a distance and cursing their own shit luck.”

Here and elsewhere in Abdurraqib’s narrative, the resemblances between his fan’s notes and Exley’s seem most evident. But Abdurraqib the boundary-breaking cultural critic, whose Go Ahead in the Rain made his readers see A Tribe Called Quest with fresh lenses, is never far away, such as when he once again ankle-breaks away from the chronological path to offer a disquisition on what he calls “The Leaving Song” subgenre of pop music, focusing on Otis Redding’s cover of the Temptations’ “My Girl” and how he “tiptoes through that chorus like he’s walking around a hardwood floor, trying to avoid stepping on glass.” Then he brings in Marvin Gaye’s “Let’s Get It On” (“a song where the question unravels until you realize, at the end, that nothing is being asked at all”), the O’Jays, Boyz II Men, and the Soul Children’s “Don’t Take My Sunshine.” All these are brought up from the basement rec room of his memories to get the reader ready for a crucial moment in the LeBron saga: the aforementioned “Decision” in 2010 to leave the talented but underachieving Cavs behind for the Miami Heat, with whom he would win his first two league championships.

Though Cleveland’s heart was broken, Abdurraqib says he understood why King James did what he did. “I’m not immune to the desire for exits. I’ve said already that I once believed my salvation would be found in another place.” Still, as the book recalls, the manifestations of the city’s heartbreak were, to say the least, intense—most especially, the setting of fires to replicas of James’s Cavaliers jersey. Then T-shirts and, “for some reason, a pair of Adidas sneakers.” He recognizes these fiery rituals as a stage of heartbreak. Still, as he notices, “so many of the people with microphones pushed into their faces in the aftermath of The Decision were white, and so much of the language affixed to that moment, out of those mouths, revolved around death, around burial.” (“He’s dead to me,” they said of James after he’d left Cleveland behind.) Abdurraqib can’t help seeing in these flames a reminder of Black urban riots in Los Angeles in 1992, in Oakland in 2009, in Miami in 1980—“in any place where black people have been conductors to a symphony of fire”—and how often these Black rioters were asked why they would set fire to “their own place.” Abdurraqib retrieves a welter of emotional responses, “about how none of this shit is ours & you have mistaken being in a place for having control over it.” Implicit in his analogy is another one of his wishes: that people who set fire to LeBron merchandise understand that their reactions are just as irrational, yet just as understandable, as the inevitable outcome of heartbreak.

I just realized I haven’t yet mentioned the “intermissions” in Abdurraqib’s four-quarter game, in which he takes deep dives into two basketball movies, Spike Lee’s He Got Game (1998) and Ron Shelton’s White Men Can’t Jump (1992). Lee’s film—about the mercurial coach-player relationship between Denzel Washington as the convict Jake Shuttlesworth and Ray Allen as his basketball-prodigy son Jesus—summons Abdurraqib’s memories of his own father, who as with Jake was a gifted player in his youth but was swept up by “the wrong crowd” that “led him to steal cars before he could even drive them.” Abdurraqib unpacks the complexities of the father-son dynamics in Lee’s movie and how the climactic one-on-one battle between Jake and Jesus symbolizes the poignant struggles of sons to shake themselves free from their father’s dominion: “a son, shedding his father one last time and becoming untouchable.”

With White Men Can’t Jump, Abdurraqib’s concerns are with the dynamics of the hustle depicted in the way Woody Harrelson’s Billy Hoyle saunters onto a playground court comprising sleek, supremely confident Black ballhawks and uses their presumptions of his dorky-white-guy inability to keep up with them as a means of separating them from their cash. Abdurraqib spins off the movie’s premise to recall how an Allman Brothers sweatshirt he’d worn at a reading in rural Wisconsin prompted confusion from whites in the audience who insisted on knowing “the deal” with the Eat a Peach album cover he was wearing. “Hustling is easiest when you are in a room people don’t believe you belong in,” Abdurraqib concludes. “All you have to do is show up and refuse to give the people what they want.” It may not be the most surprising or even revelatory of his many insights—except for the credulous Americans for whom such cultural transactions remain astonishing or confusing.

And we’re back on the clock. If you’ve followed basketball in the last decade or so, you know how the story turns out: James returns to Cleveland and finally delivers to his city and their now forgiving fans an NBA trophy in 2016, their first sports championship in fifty-two years. Abdurraqib was in a Connecticut sports bar when Cleveland’s fondest wishes were finally granted and watches the historic seventh and deciding game of the finals whose “fourth quarter felt like five lifetimes, all of them hard on the heart, even if one had no direct rooting interest.”

Not long after that game, and Abdurraqib’s return to Columbus, a twenty-three-year-old Black man named Henry Green was walking back to his aunt’s house when he was shot dead by Columbus police, a victim of the city’s so-called Summer Safety Initiative. “I wondered, foolishly, perhaps, if this would be what it took to dislodge a city from its comforts, rattle people at least somewhat permanently out of the self-made mythology of a clean and holy place.” There were protests, but Abdurraqib knows that protests aren’t something you win or lose, as in a game.

Maybe, a reader might wonder, it’s just gravity—a law guaranteeing that every ascension that comes with the fulfillment of a wish is followed by a fall to Earth, whether soft like a feather or hard like a building. Abdurraqib’s chronicle doesn’t directly say this. But as the seconds tick away in the fourth quarter of his riveting game, he accepts the pattern, the persistence of dreams continuing into their own ongoing cycle, the way Brian Wilson says he wanted to fade “God Only Knows” with a loop of the chorus, “a sort of infinity spiral.” And if you’re inclined to wonder, even at this late point in the action, why Abdurraqib thinks Brian Wilson has anything to do with basketball or everything else he’s been dealing with, then maybe you need to turn the play clock back to the first quarter and, this time, be prepared for the break.

Gene Seymour is a writer living in Philadelphia.