ALEXANDER POPE, WROTE NICHOLSON BAKER in a roaming 1995 essay about allegorical uses of the word “lumber,” was “one of the most skilled word-pickers and word-packers in literary history.” Across three erotic novels, seven non-erotic novels, four nonfiction books, two essay collections, and one work of autocriticism about John Updike, Baker has proved himself to be among the great picker-packers too, especially in the fertile, anything-grows orchards of figurative language. Similes, analogies, metaphors, and euphemisms are Baker’s uncontested territory. Few areas of knowledge have evaded his encyclopedic curiosity, which means he can compare a piece of machinery to another piece of machinery, or a piece of machinery to a sex organ, or a sex organ to a New Yorker staff writer, and it’s usually persuasive. Get a load of the breathtaking density of objects crammed into this single sentence about a vacuum cleaner: “To restore the machine to full suction, you had to dig around in the curved whisps of dog and cat fur that collected in a tub, like cotton candy in a floss bowl, and twist to release a central perforated tube, then pry out a sandwich-sized filter and thumb it manually, as if you were strumming a zither.” Or the scene in his 2016 memoir about working as a substitute teacher in Maine public schools, in which Baker and some fifth graders “walked to the cafeteria, where there was a massive molten fondue of noise.” The narrator of his first novel, The Mezzanine, appreciates old-school turn-signal levers that “move in their sockets like chicken drumsticks.” “I can and do wear socks all day,” Baker writes in 2003’s Box of Matches, “that have a monstrous rear-tear through which the entire heel projects like a dinner roll.” “Formerly dull-seeming tidbits of history,” collected in a recent book, “glowed like cherry tomatoes in the picnic salad of the twentieth century.”

This kind of thing can make a person positively hungry. (Baker’s descriptions of literal food are just as good: at a publishing party, he describes being “forced to eat sliced and stuffed things at traypoint.”) More broadly, the effect is an expansive, energizing sense of de- and re-familiarization, a psychedelic recognition that the built environment is linked to itself in all kinds of mysterious and pleasing ways. One begins, in heavy-duty Baker-reading periods, to look around and feel that the entire physical world—its glimmering matrix of information technologies and engineering triumphs, plastics and snacks—is up for associative grabs.

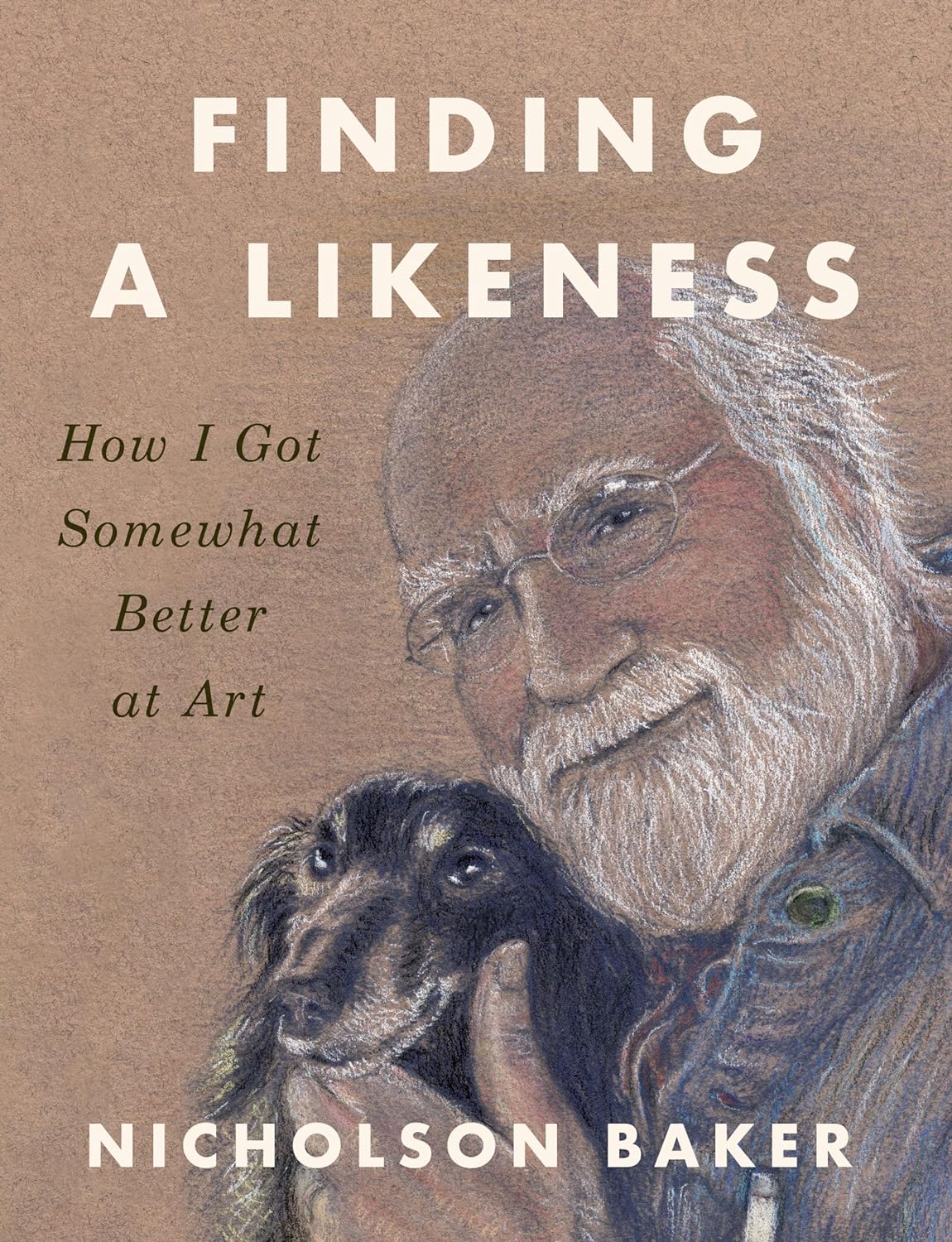

Finding a Likeness, the title of Baker’s new memoir, is suggestive of his career-spanning analogical concern. What’s Baker been doing all this time, if not finding tender, outré likenesses everywhere he looks? Now he has tried out a different kind of looking: Finding a Likeness chronicles two years in which Baker took a break from fiction and literary journalism to teach himself “how to draw and paint on the far side of sixty,” recasting his interest in figurative language as a new focus on figurative art. The mechanics of getting “somewhat better at art”—the mimetic skill that drawing demands, the “erasefully slow” temporality imposed by shading a landscape or still life, the robust universe of instruments and tools (longtime Bakerian subjects) available to the amateur artist—echo many of his lifelong literary concerns. But the essential irony of the book—one Baker is way too humble to name—is that we spend much of it watching one of the best describers alive struggle with the basics of representation.

Long before he turned to visual art, Baker was writing images. (There’s a generally synesthetic quality to much of his prose—blurbs on the back cover of my copy of Vox compare the novel to both Chagall’s drawings and Ravel’s Bolero—but the dominant mode, the sensory system to which he defaults, is the visual.) Baker’s exhilarating similes belong to a larger project of capturing how everyday things look in ultra-high-resolution detail; his sensibility, he admits in the early memoir U and I, is “image-hoarding.” Also in that book, in which Baker reflects on his literary indebtedness to John Updike, he refers to Updike’s image-forward style as “Prousto-Nabokovian,” one of many admiring epithets in the memoir that could equally apply to Baker himself. (I just don’t believe Baker, who in his previous book had described a woman’s pregnant belly as “Bernoullian,” and her pubic hair as “brief,” when he claims to envy Updike’s “adjectival resourcefulness.”) Nabokov’s crisp molecular comedy, his tendency toward anthimeria and dryly upcycled technical language, his cliché-demolishing descriptive precision; Proust’s luxuriant digressiveness, his great subject of time, and above all his sublime animation of psychological riffs by visual cues: already, by 1991, it was clear that these were Baker’s gifts too.

The two novels that preceded U and I—1988’s The Mezzanine and 1990’s Room Temperature—had established Baker’s imagistic method. Both novels take place over the span of less than an hour. Each records the thoughts of an appealingly intelligent first-person narrator as he attends to a routine task: workday lunch break; feeding infant daughter. These narrators bubble with what The Mezzanine’s Howie calls “mechanical enthusiasms,” and their inner monologues slip into warm and jazzy studies of twentieth-century manufactured objects: staplers, dustpans, milk cartons, HVAC systems, stamps. Baker’s associative, detail-rich descriptions of this stuff can resemble an especially exuberant species of product photography, entries in history’s most charming industrial supply catalogue. “Anything, no matter how rough, rusted, dirty, or otherwise discredited it was, looked good if you set it down on a stretch of white cloth, or any kind of clean background,” Howie muses. “Anytime you set some detail of the world off that way, it was able to take on its true stature as an object of attention.” What flowed from this philosophy—which Finding a Likeness, in its own way, returns to—was an experiment in the near-total subordination of storytelling to image: in cheerfully materialist white-collar fiction that really sees the means of production.

WHO WAS DOING ALL THAT EXTRAORDINARY SEEING? Baker’s early narrators were affable, horny, ecstatically attentive noticers, almost always men, who have in common a Pnin-like delight in the physical infrastructure of modernity. (Nabokov: “Electric devices enchanted him. Plastics swept him off his feet. He had a deep admiration for the zipper.”) The comedy lay in the scalar discrepancy between their all-seeing knowledge of “the way the world works,” as the title of a 2012 collection of Baker’s essays has it, and the uneventful, zoomed-in, low-stakes subjects they gamely applied it to, like if DeLillo wrote an episode of Seinfeld.

One does occasionally get the sense that these guys’ mechanical enthusiasms may flourish at the expense of other kinds of understanding. They’re curiously unaffiliated: typically they have jobs—solid ’90s jobs like word processor—but little sense of institutional belonging; they might have wives or girlfriends but conspicuously few friends. (“Friends, don’t have any” appears in The Mezzanine in a catalogue of Howie’s thoughts—sorted by frequency—below “Panasonic three-wheeled vacuum cleaner, greatness of.”) When they encounter other people who aren’t babies or John Updike, it is often via some mediated or object-oriented process: Howie surfaces from his mesmerizing private reveries only to speak to cashiers and secretaries behind desks and machines; the narrator of 1994’s The Fermata (a terrific and under-theorized novel that allegorizes the temporal powers of fiction as even Proust couldn’t do) has the supernatural ability to pause time, and spends most of the book freeze-framing the human world so that he can do dirty things to women. One novel, Vox, takes place entirely over the phone.

In his middle novels, Baker’s preoccupation with objects and images—with making them knowable and, unique among his TV-and-tchotchke-obsessed contemporaries, with making them likable—began to accommodate an expanding interest in character. Vox, the first book in Baker’s loose erotic trilogy, contains some of the old emphasis on solitude and mediation; one character admits that an evening spent with a coworker, watching porn on VHS, was “probably the best sexual experience I’ve had, or at least one of the elite few.” But the novel, occasioned by a chance encounter via sex hotline, also registers real connection between strange minds casting about and alighting not just on objects and how they look but on people and how they feel.

“Sometimes I think with the telephone that if I concentrate enough I could pour myself into it and I’d be turned into a mist and I would rematerialize in the room of the person I’m talking to. Is that too odd for you?”

“No, I think that sometimes,” he said.

Something has shifted here: a newly outward-facing orientation, a wider aperture of attention. Rereading these surprising and funny mid-career novels, I remembered one of the many tossed-off kernels of publishing sociology in U and I. Auditing his own tendency toward “louped scrutiny” in contrast to Updike’s mature works, Baker wrote that “the metaphorical sense, along with the flea-grooming visual acuity that mainly animates it, fades in importance over most writing careers, replaced, with luck, by a finer social attunedness.”

Flea-grooming! He really had his own number. But social attunedness did arrive in Baker’s later work, which became larger in scope and less buoyed by pure enchantment as the mellow ’90s came to a close. Seinfeld ended. Underworld came out. It became clear that emergent digital systems threatened to destroy all kinds of library collections, newspaper archives, film-storage methods—the very best of the twentieth-century world of things—and Baker wrote a series of books and reported pieces about analog media preservation and the people attempting it. The United States invaded Iraq, and Baker, possibly the most famous pacifist in contemporary American letters, adjusted his lens again. His fiction and nonfiction has, since the beginning of the war on terror, circled the subject of American war crimes, from a controversial work of history about the unjust aims and methods of the Allied powers during World War II to the 2004 novel Checkpoint, which follows two guys chatting about assassinating George W. Bush. (Bakerian pacificism and uneventfulness triumph in the end: the guys don’t go through with it.) In 2020, Baker published Baseless, a diary of his only partially successful attempt, using the Freedom of Information Act, to learn about the United States’ likely use of illegal biological weapons during the Cold War.

These are heavier, lower-key books, anchored by a tone of powerless disappointment in a country that, in addition to producing all kinds of interesting machinery and realist fiction, also kills civilians with impunity. The subject is now undeniably people (the individual perpetrators of war, and their victims); the scope increasingly far-reaching and historical. But even Baker’s most systems-level, bird’s-eye writing can’t quite shake the old enthusiasms. Baseless, in particular, veers between the global and the granular, placing Baker’s harrowing research findings—declassified CIA documents; evidence of inhumane epidemiological experiments conducted by the Air Force—alongside scenes from his daily life: Quaker meetings, dreams, funny stuff his wife says, updates on the couple’s dogs. The book unfolds like a FOIA document from some alternate and more transparent universe, with no part of political life redacted: not the unbearably gigantic horizons of atrocity and left defeat that loom over the American project, nor the small pleasures that one might turn to in the shadow of those losses. “The recent overarmed era in the million-year history of our species has been difficult,” he writes.

And yet think of all the greatness of the twentieth century. The music, the magazines, the movies. The Russians Are Coming, for instance . . . Saul Steinberg, Tracy Chapman, Nabokov, Maeve Brennan. Aretha Franklin. The century of observation and improvisation.

AFTER BASELESS, BAKER WAS “WIPED OUT. I needed a rehabilitation program. A less bleak way of looking at the world.” As it did for Bush himself, visual art seems to Baker like a good choice—a way to zoom back in and return “observation and improvisation” to central focus. In 2019, after handing in his book and a few months before the pandemic began, Baker set about learning to paint.

Finding a Likeness gathers artwork that Baker sees online and likes—a nicely egalitarian selection of nineteenth-century master portraiture, Art Deco magazine illustration, and contemporary realist paintings in oil and gouache—alongside Baker’s own attempts. His first subjects recall the small commonplace objects that starred in his early novels: leaves and glassware and a metal easel clamp. He hopes to get good enough to paint clouds (“puffy, huge, lunglike, breathing, hippopotami of the sky”) and seeks out examples from modern art history: “Maxfield Parrish’s heaped, beehive-hairdo clouds fill me with shuddering, bulbous joy.”

Baker’s paintings and drawings appear on nearly every page. The earliest works have the lumpily dutiful quality of high school art class projects. “The brush was an impossibly clumsy tool—not a rational way to apply pigment to a surface,” he writes. (Elsewhere, more baroquely, he calls his paintbrush a “glop-tipped eraserless mop-flopping palette-puttering art wand.”) He’s bashful about, occasionally “disgusted” by, his own work, and some of the book’s best lines—its best similes, especially—come from his most self-critical self-ekphrasis. One drawing “looks a little like Beavis in Beavis and Butt-Head.” In a suburban landscape painting, a car “comes out looking like a pool table.” Trying another car, “I lost my temper at one point and typed, ‘I HATE THIS TOAD OF SHIT THAT HAS EMERGED FROM MY BRUSH.’” The comparison is apt, as usual—his Honda painting really does have an amphibian quality.

There’s an invigorating novelty in seeing a master try something new without immediately becoming virtuosic, like Ornette Coleman teaching himself to play the trumpet. But it’s not the first time Baker or one of his semi-autobiographical characters has switched forms. Before he was a writer Baker played the bassoon, and his fiction surely features American literature’s largest quantity of failed bassoonists. Paul Chowder, the narrator of two essayistic later novels, is a bassoonist turned poet who, in 2013’s Traveling Sprinkler, decides to switch gears again and write songs, as “a way of paying attention to a single event by surrounding it with many notes.” He buys a guitar and composes protest songs about Obama’s foreign policy, plus folkie numbers about his daily surroundings: “Native peaches / fresh tomatoes / lots and lots of corn / Hot blueberries / cold chicken / and ridiculous amounts of porn.” There is no great effort made to persuade us that these are especially artful songs. “What is it when you have an urge to produce something,” Chowder wonders, “to make something, and it almost doesn’t matter whether it’s good or not?”

The same spirit of easygoing exploration surfaces in Finding a Likeness. Baker takes a couple painting lessons, experiments with different methods and tools, finds “gorgeously unremarkable” objects and scenes to sketch. (Central Maine, where he lives, furnishes him with all kinds of half-ugly, half-beautiful subject matter. “I found some good clouds near a Chipotle restaurant,” he writes, contentedly summing up all of contemporary America.) There are perhaps fewer descriptions of materials than one might expect from a writer who once gave us the memorable paper-goods anthem “Perforation! Shout it out!” but the meditations on sandpaper grain and oil pastels are highly satisfying. “Pastels: loaves and lozenges and ingots of baked radiance that would stain my fingers and dust my optic nerve,” he writes. “It’s dry from the beginning. No brushes needed. You just wipe your hands on your pants.”

Already this is, as Baker likes to say, awfully good. But then, over the course of the book, something like his career in miniature unfurls. Baker’s initial interest in visual art as a means of paying attention to the inanimate world—to still scenes, small tools and landscapes, cool clouds—gives way to a fascination with the human form, specifically the human face. He becomes prolific in portraits, sourcing references from a Reddit forum. “I especially liked drawing smiley couples,” he writes. “And parents and children, and people and their dogs. Actually I liked drawing every sort of person, except people with septum piercings, because it’s too difficult to draw shiny hardware when it’s lurking in the shadows of a pair of nostrils. Nostrils on their own are hard enough.” Taking a light detour into art history, he argues persuasively that smiles, generally, are underrepresented in Western art.

Baker’s portraits improve in a big way as the book goes on, especially as he incorporates tracing into his drawing method. (Baker’s search for visual accuracy—for the sort of realist precision that his fiction has always elevated—provides the memoir with about as much of a plot as his books ever have.) The later drawings are confident and warm, especially as he begins drawing his children, parents, and wife. “The thing about drawing someone you love is that you have a chance to think uninterruptedly about the nature of your love and the details of your love,” he writes. The process, on the whole, forces him to look closely at his human subjects. “As soon as I began sketching, usually at the person’s right eye, I felt a quietness and a surge of attentive committedness.” Or, elsewhere: “I drew him, and I knew him.”

IS IT TRUE THAT TO DRAW SOMETHING IS TO KNOW IT? I was reminded throughout Finding a Likeness of one of the last books by John Berger, Bento’s Sketchbook. Berger and Baker share a lot: an inviting and companionable appreciation for sensory experience, a gift for erotica, an unusual investment in seeing aesthetic beauty as it exists alongside—sometimes as the result of—imperial violence. (They also have in common a certain tactile sensibility: an extended analogy in Bento’s Sketchbook between the mechanics of sketching and of piloting a motorbike—“You are riding a drawing”—rhymes nicely with this description, in Baker’s Box of Matches, of falling asleep with his wife: “She turned and shifted her warmly pajamaed bottom towards me and I steered through the night with my hand on her hip.”) Berger, of course, was a painter as well as a writer, and in his book, as in Baker’s, annotated sketches are reproduced alongside short meditations on drawing and what it does to the mind. Berger draws flora from his mostly rural surroundings: herbs and fruit in France, an olive tree in Palestine. Even more than a way of encountering place, a sketching practice, for Berger, was a means of finding solidarity with people. In between portraits of his neighbors, the writer Andrei Platonov, and Jesus, he considers the practice’s effects at the human scale. When drawing, Berger writes, “I’m aware of a distant, silent company.”

Baker reaches for company, too. As his skills improve, he begins sketching artists and political figures who have been meaningful to him. A sense of purpose settles in as he makes a portrait of Tracy Chapman, one of the gems of the twentieth century he named in Baseless. “When I was working on the drawing I was calm,” he writes.

The world was a mess, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren weren’t getting along, but the important thing at that moment was to try to do right by Tracy Chapman’s wistful, glowing smile. While I worked I sang bits of her songs to myself. . . . I want to do this from now on, I thought—draw people whose lives add beauty. And paint them, eventually.

An idiosyncratic personal portrait gallery takes shape. He draws Jean Cocteau, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and a version of René Magritte that “looked like George Harrison.” John Lewis, Anaïs Nin, Nabokov, the guy who invented the Swingline stapler. (“I used a wiry sort of style, as if all the world was made of bent staples.”) Rachel Carson, E. B. White, a very good Jean Stafford, antiwar activist Frances Crowe. Susan Sontag, Gary Shteyngart, Mary Cassatt, Adam Schlesinger from the great power-pop band Fountains of Wayne. Even when he gets his idols wrong (“I got the urge to draw the founding editor of The New Yorker, Harold Ross. I thought he might be easy because he has such strong features, and such a flume of hair. I tried twice and stopped. I’d made him look like a boxing promoter”), the process encourages a humane clarity. Despite Baker’s self-avowed attempt to take a break from political writing, a pacifist current surges through the book, evident in the subjects Baker has gathered. “It was a privilege to be tracing the outline of her cheekbone,” Baker writes about drawing Dorothy Day, “feeling the strength of it, knowing how many days and years she spent writing editorials against wars.”

This is far from the hammy, self-conscious, slightly neurotic influence-anxiety of U and I, in which Baker the young novelist positioned Updike as a maddening “imaginary friend” whose aesthetic shadow had to be wrestled with. Yet it’s hard not to read Finding a Likeness as a companion to Baker’s first memoir, a return to the questions of craft and influence that U and I set out to explore. Finding a Likeness is a quieter book, as Baker’s later work has tended to be. You feel that Baker has grown out of certain things, or grown into them—maybe even into the “air of rangy assurance” that he once envied in Updike. What could be more rangy and assured than showing the world your first wobbly artworks? (Updike, I remembered while reading the new book, was himself a trained artist.) In place of Baker’s old image-hoarding style is a less flashy, smudgier, more serene approach; in place of solitary preoccupations, a more expansive embrace of artistic indebtedness. “I started to feel that I wanted to spend the rest of my life doing portraits,” writes Baker. “In fact I wanted to draw every person in the world.”

Lisa Borst is the web editor of n+1.