LIKE MANY PEOPLE, I FIRST SAW JILL JOHNSTON in Chris Hegedus and D. A. Pennebaker’s indelible film Town Bloody Hall (1979),which documents a raucous 1971 “dialogue on women’s liberation.” Norman Mailer, the panel’s token misogynist and nominal moderator, introduces Johnston as “that master of free-associational prose in The Village Voice,” for which (I’d later learn) she had written regularly since 1960. When she takes the lectern, you can see in the faces of the audience members that at least some of them suspect what they’re in for. Johnston, dressed in ornately patched jeans and a denim jacket, takes off her sunglasses before launching headlong into a riff reminiscent of Gertrude Stein: “All women are lesbians except those who don’t know it naturally they are but don’t know it yet I am a woman and therefore a lesbian I am a woman who is a lesbian because I am a woman.”

The rant slows and loosens as she begins to crack herself up. Germaine Greer throws her head back and claps at the line, “He said I want your body and she said you can have it when I’m through with it.” Suddenly we’re watching vaudeville. Mailer stares at the table and fingers his pencil. When he tries to enforce a time limit and cut Johnston off, the audience boos—they might not have been following her argument, such as it was, but most seemed to enjoy it well enough. Out of nowhere, a woman steps onstage and begins to hug and caress Johnston. Another appears, asking, “Hey Jill, what about me?” All three roll around on the floor together.

Was Johnston for real? In his discomfort Mailer tries to separate the substance of her remarks from the unserious way she presented them. “I want to talk to you about lesbianism, God damn it,” he scolds her. “Now, you can play these games, but they’re silly.”

When I finally read Johnston, years after watching Town Bloody Hall, I found that silly was hardly out of character. She made her name as a critic of avant-garde performance at its most outré. Her reviews introduced readers to dances that were barely recognizable as such—“perfect and meticulous nonsense,” as Johnston described a 1964 Lucinda Childs piece in which the choreographer put sponges in her mouth and a colander on her head. In 1968 and 1969, Johnston even mounted her own works of performance art in the guise of academic panels, adopting the conventions of civil exchange in order to thumb her nose at them. For a “panel performance” at New York University’s Loeb Center in October 1968, she wrote a script of random actions (“pretend to have a headache,” “yawn extravagantly”) and clichéd statements (“That’s an interesting question,” “You’re full of shit”) for her co-panelists to choose among at random. “What is a panel?” she asks in a Village Voice column that recounts the evening with more than a hint of pride. “Panels are a big drag, that’s what they are.”

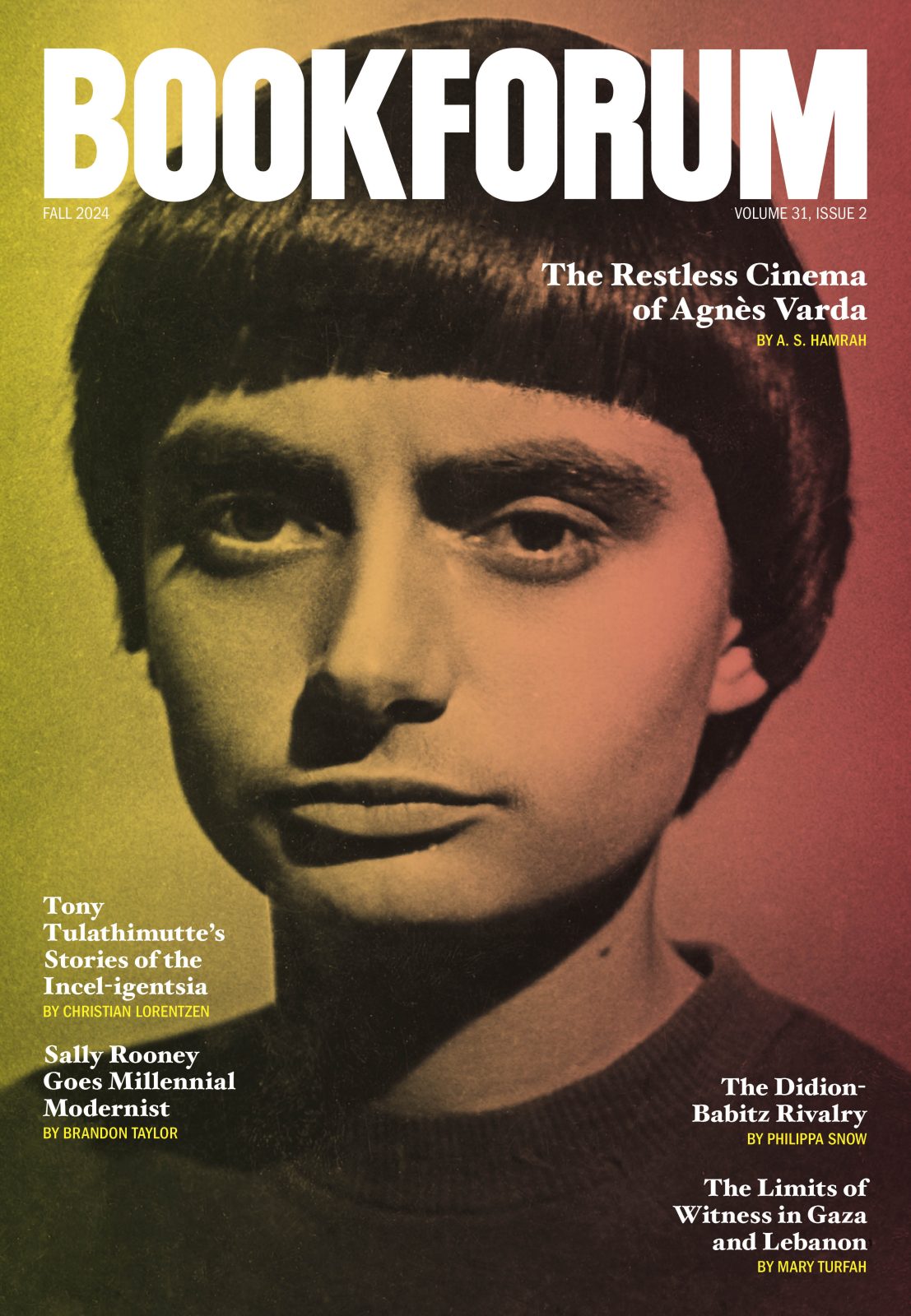

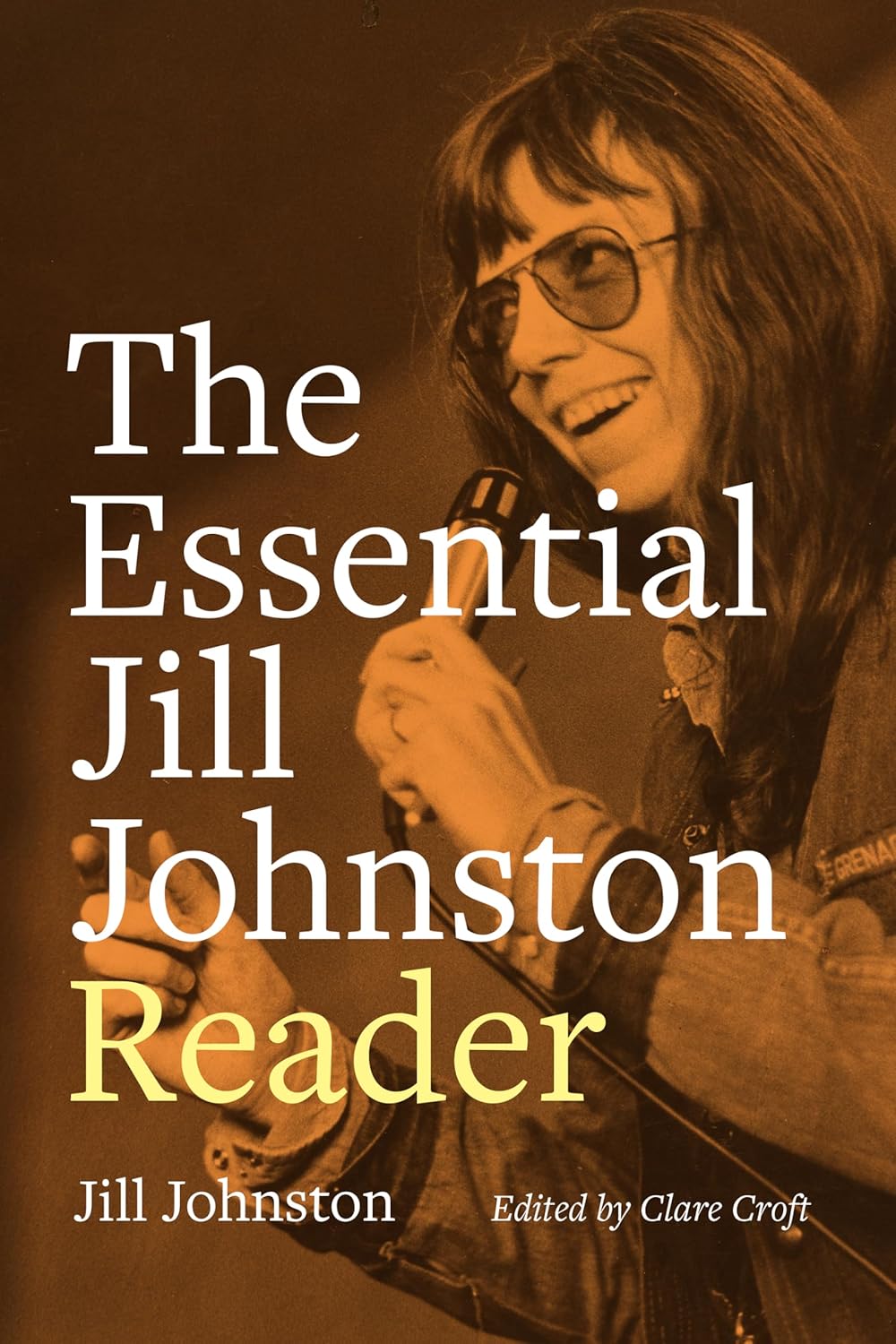

That Voice column, “The Unhappy Spectator,” is included in the new collection The Essential Jill Johnston Reader, edited by the dance scholar Clare Croft. The book reprints the performance criticism for which Johnston became famous in the 1950s and ’60s alongside the lesbian-feminist polemics, provocations, and personal reflections to which she turned in the ’70s. As Croft argues in a companion study, Jill Johnston in Motion,it’s only by looking at these two stages of Johnston’s career side by side that each can be seen clearly. Latent political instincts guided the experimental performances she reviewed and sometimes participated in, and scrupulous aesthetic principles underlay her activist hijinks.

Those principles could be hard to discern. Both her writings and her actions often looked farcical. “The Unhappy Spectator” describes eminences literally brought low: the dancer Trisha Brown crawled across the table, and a man from the audience tackled Johnston out of her chair. (In the column, Johnston admits her surprise, writing, “I’d forgotten that gesture instruction to wrestle somebody to the floor.”) As the chaos spread and nerves frayed, Johnston seemed most gratified by a woman “who mounted the stage at last to burn the place up in a plea for love.” All the slapstick, absurdity, and indecorousness had granted permission for an honest expression of unmet need. Johnston marvels, “She was absolutely for real.”

Reading Johnston can feel like stepping through the looking glass, and not only because of the apparent surrealism of crawling dancers and screaming audiences. Over and over, she makes a bravura show of putting you on, “playing superbly at being ridiculous but stylish and excellent although absurd,” as she wrote in 1971. Her panel performances were provocative, but not arbitrarily so: they combined the participatory ethos of artist Robert Whitman’s Happenings, ideas about indeterminacy popularized by composer John Cage, and the antagonism of Antonin Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty in service of a distinctly late-’60s critique of hierarchy and heterosexism.

“What’s at stake is the question of authority,” Johnston wrote in “The Unhappy Spectator.” She had spent a decade becoming a charismatic representative of artistic assaults on charisma, celebrating new styles of dance whose everyday gestures—walking, lying down, picking up and dropping things—risked boredom and offense. Like the artists she championed, Johnston’s methods could be sexy, aggressive, annoying, or enraging. She would goad or seduce her audiences into responsiveness. She wrote the instruction: wrestle her to the floor.

Authority—who wields it and how—was also the question at stake for feminism and gay liberation. Around 1970, Johnston reinvented herself as a jolly militant and lesbian prankster, charming and irritating her sisters by turns. She derailed a Ti-Grace Atkinson speech by propositioning Atkinson from the audience; she derailed an East Hampton fundraiser by undressing poolside and swimming laps. Like the performance reviews that preceded them, these antics were often trivialized as mere mischief. In a prescient 1960 column about a program of Happenings, Johnston preempted such criticisms: “It was serious because it came out of a thoughtful revolt against a world in chaos that was pretending order.”

THOUGH HER REMIT WOULD WIDEN as her writerly ambitions grew, Johnston was recruited to the Voice to cover dance. As Croft notes, the link in Johnston’s work between performance and lesbianism was biographically literal: in college Johnston’s first dance professor became her “first female lover” and encouraged her to move to New York to continue her training. She joined the school of José Limón, who developed a baroque, sentimental style of modern dance against which Johnston soon rebelled. She was talented but a poor fit for the “conventionally feminine” roles on offer.

Johnston’s dance career ended when she broke her foot (she claimed to feel “greatly relieved”). Her new career in writing began after she sent a critical letter to Louis Horst, editor of Dance Observer,who was impressed enough to invite her to contribute to his magazine. “At that time I wasn’t living in this century at all. I was living in a museum,” Johnston later recalled. “At some point travel accelerated and I think I woke up one morning and stepped out the door into the twentieth century.” The earliest pieces in Croft’s Reader imply a more considered transformation. In essays for Dance Observer from 1955 and 1957,Johnston plants herself on the threshold, with one eye turned to the canon and the other drawn out to the street. Her tone is professorial, sometimes ironic but not yet self-ironizing.

She “deposed” Limón’s generation of moderns but raised no single banner in their place; her reviews worked hard to understand a dance’s goals and premises, whatever its style, so that she might experience it fully. This “critical generosity,” as Croft calls it, made Johnston receptive to new kinds of performance emerging downtown in the early ’60s, thrillingly poised between dance and visual art. Johnston’s legacy has been most closely associated with the Judson Dance Theater, a fiercely experimental cluster of choreographers including Childs, Brown, Steve Paxton, and Yvonne Rainer, who all alighted on Judson Memorial Church in 1962. Johnston appeared in their work and reported from their parties.

Croft attempts to loosen the yoke tying Johnston to Judson, fearing that it obscures the breadth of the writer’s interests and the longer arc of her career. But the unstable binaries that preoccupied the Judson dancers—artist and audience, planning and chance, athletic precision and habitual motion, joking and meaning it—were also at the heart of Johnston’s own work.

As dance expanded to include new settings, subjects, and postures, Johnston’s column expanded with it. In the mid-’60s, Johnston undertook dramatic experiments in her own writing, seeking not simply to describe but to reproduce her favorite performances on the page. In a 1968 column, she writes approvingly, “Paxton brings the street into his theatre. Or puts the theatre back on the street”—after narrating a walk around town with the choreographer and Robert Rauschenberg. She began dispensing with commas and paragraph breaks. One of my favorite quotes in Jill Johnston in Motion is from Johnston’s editor Diane Fisher, who throws up her hands: “We are, Jill, after all a newspaper!”

Johnston was no longer content to evaluate art. Now she was making it. Her final panel performance in 1969, meant to mark her abdication of the seat of judgment, was titled “The Disintegration of a Critic.” (In 2019 Sternberg Press published a collection of Johnston’s Voice columns under the same name.) The cellist Charlotte Moorman sat at one end of the table wrapped head to toe in muslin. Andy Warhol sat at the other, snapping pictures with his Polaroid. Johnston arrived at 10 pm and read some pages that her editor had just cut. In his account of the evening for the Voice, John Perreault wrote, “In some sense, she has become a visionary and this is both embarrassing and important.”

IN THE SAME YEARS THAT JOHNSTON reaped ever-wider swaths of her life for her columns, feminists and gay liberationists were dismantling the boundaries between public and private. Coming out became at once an aesthetic and a political obligation for Johnston, who had married and had two children with a man before divorcing in 1963.

Johnston first publicly declared her lesbianism in a July 1970 column, though Croft notes that devoted fans had already picked up on it. Women waited outside the Voice office for her latest dispatches, hot off the press. (As Johnston later wrote of her political awakening, these were years when “waking up was a kind of epidemic, highly communicable and often fatal.”) Croft also highlights Johnston’s occasional caginess about her identity, a pose that offered in-the-know readers something Croft terms “recognition without confirmation.” Johnston wanted to challenge narrowly sexual definitions of lesbianism, broadening it to include the fullness of daily living—just as her favorite performers had done to dance, and just as her columns had done to criticism. But even though she sometimes refused to pin down her queerness, Johnston also embodied and wrote about lesbianism in newly “exaggerated” ways. She took seriously the liberationist imperative to come out clearly and proudly, and thereby “clarify my life.”

Looking back at the women’s movement through the lens of Johnston’s career, we can see that many of its leaders were likewise indebted to the previous decade’s aesthetic experiments. What was Robin Morgan’s infamous protest of the 1968 Miss America pageant if not a feminist Happening? What was the toilet Kate Millett brought to a 1967 demo against hiring discrimination if not a Fluxus sculpture? Despite these clear lines of affinity, Johnston never felt at home in movement spaces. Because the mainstream press tarred all women’s liberationists as man-hating lesbians, many straight feminists anxiously distanced themselves from queer women well into the ’70s. Johnston knew that some of her nominal sisters considered her a liability.

In this light, Johnston’s stunts have a sharper edge: rather than tone herself down, she would bring the straight world’s discomfort to the surface. The East Hampton fundraiser at which she took her unauthorized swim was hosted by art collectors Robert and Ethel Scull and presided over by Betty Friedan, who had decried lesbians as a “lavender menace” months before. When Johnston jumped in the pool, she made the scene that Friedan feared. In her column “Bash in the Sculls,” Johnston describes being besieged by journalists who wanted to know why she did it, to whom she explains—sort of, “I think one should be serious in one’s purposes but not necessarily solemn. . . . It was a Conceptual Swim.”

Johnston’s courage made her something of a folk hero, but she wasn’t the most reliable ambassador for lesbian politics. Her more theoretical writings improvise deftly with the activist vocab of the time but don’t aim for discipline or consistency. She hits familiar radical-feminist notes about women’s sexuality being bedrock to all forms of power and about the polymorphous pleasures awaiting us after the revolution. She also echoes other white feminists’ racism and transphobia, calling “transsexualism” a “monstrosity” and instrumentalizing Blackness in anxious but offhand ways. (Unlike a lesbian, who must announce her identity, “A black person these days has a certain advantage in being clearly black.”) Ideas bubble up and sink again in the columns’ stream of language. The unifying force is personality, as well as the stamina required to make one bold, curious gesture after another.

JOHNSTON’S CHARACTERISTIC RESTLESSNESS led her away from the movement almost as quickly as she’d joined it. Her writerly ambitions changed form once more; after her 1973 book Lesbian Nation,Johnston aimed “to write the third unreadable book of the century—following ‘Finnegans Wake’ and ‘The Making of Americans.’” (She instead published a series of autobiographies and a study of Jasper Johns.) In a 1993 essay, which concludes the new Reader, she confesses that “politics definitely cramped my style,” and the breathless voice of her Voice columns came to feel ill-suited to her deepening interest in family history. Like so many of her activist peers, she found revolutionary optimism impossible to sustain amid waves of backlash. Already by 1975 she felt that feminists “had to jump ship and swim for their lives, or go down in a whoosh and bubbles of martyrdom. It was not hard for me to choose.”

In 2004, Johnston joined co-panelists Greer and Jacqueline Ceballos, former president of the New York chapter of the National Organization for Women, at a “reunion” of the 1971 debate documented in Town Bloody Hall. The moderator Marlene Sanders asked Johnston if her stunt had been a way of “putting down the whole thing,” to which she conceded, “Yeah, probably.” Johnston disclosed that her ambitions had been far greater: “My idea had been to take everyone with me and destroy the event altogether”—The Disintegration of a Feminist—but no one joined her. When the dust of her notoriety settled, she had no choice but to “start again.”

At the end of the reunion, Pennebaker gave Johnston a big hug. As if to reassure her, he said, “You were definitely the queen of the ball.”

Sam Huber is a senior editor at the Yale Review and is writing a biography of Kate Millett.