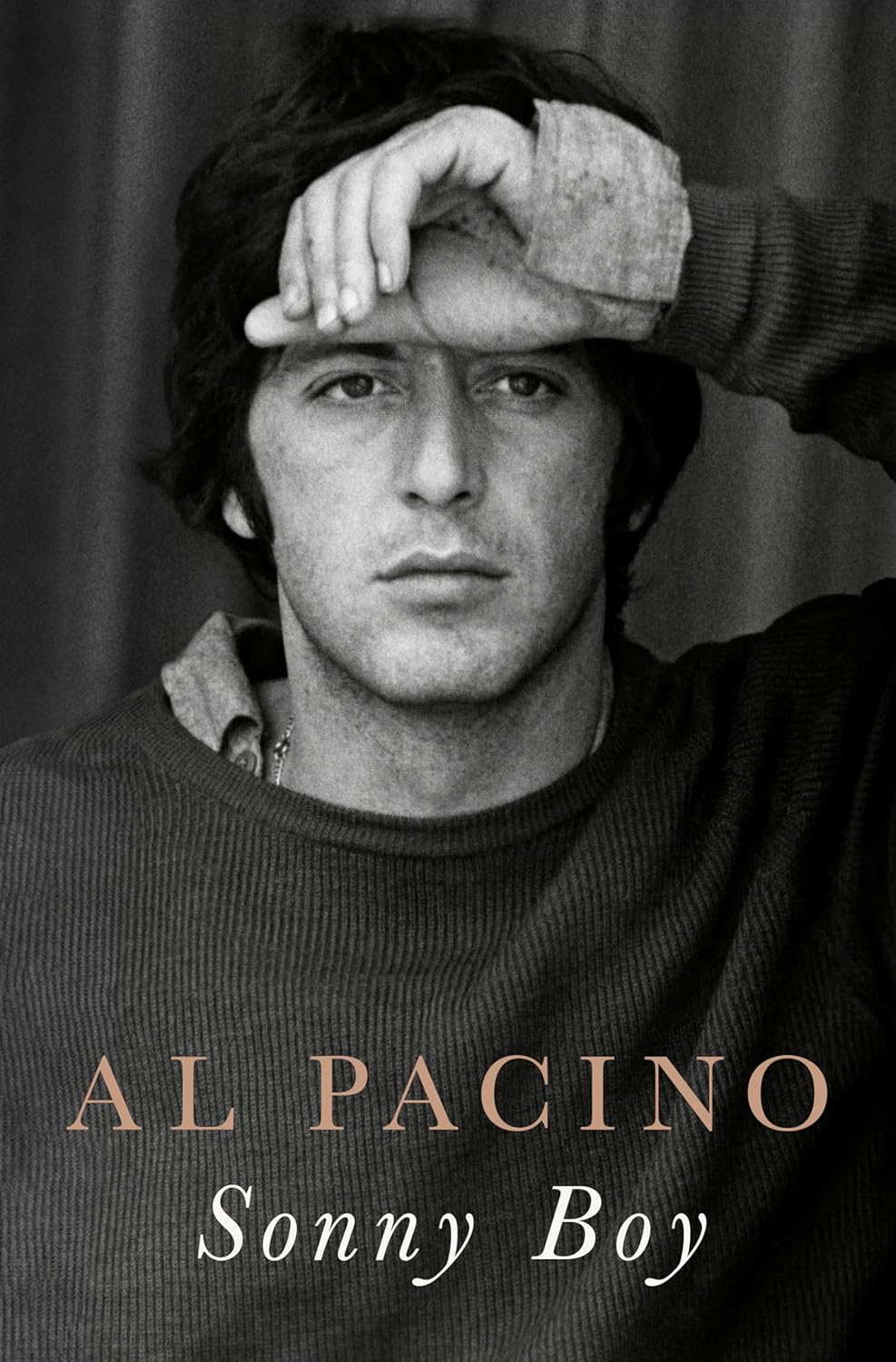

IT HAS BEEN SAID that in his greatest roles Al Pacino plays characters who through temperament and actions—whether noble or nefarious—wind up utterly alone. Cut off, even, from some vital part of themselves, the mercy or cynicism that might have restored balance to their lives. But what Al Pacino character craves balance? His Frank Serpico is a freewheeling New York City plainclothes officer in bell-bottoms and a bucket hat whose dream of being a cop is directly contradicted by the reality of being a cop; his Michael Corleone, diabolically bent on providing for his family, amasses nothing but power for himself. These characters have unconventional, sometimes inexplicable instincts, and are made painfully aware of this fact, but Pacino’s performances are never resigned or withdrawn. On-screen he is like a full-grown man digging furiously in a child’s sandbox for a rock to throw at anything. Each word is given its own volume and pitch—yielding at times those signature Pacino detonations that deliver a jolt of adrenaline and significance at once. Meanwhile his gaze moves fluidly between seduction and alienation. One feels in those eyes the shock of each successive moment on earth; though consumed with existential isolation, they still spy in the middle distance something that fascinates or haunts them. There is the action of the commercial film—carefully blocked, calculated, compromised on—and then there is the action of those eyes, which don’t quite seem to know what they’re looking at.

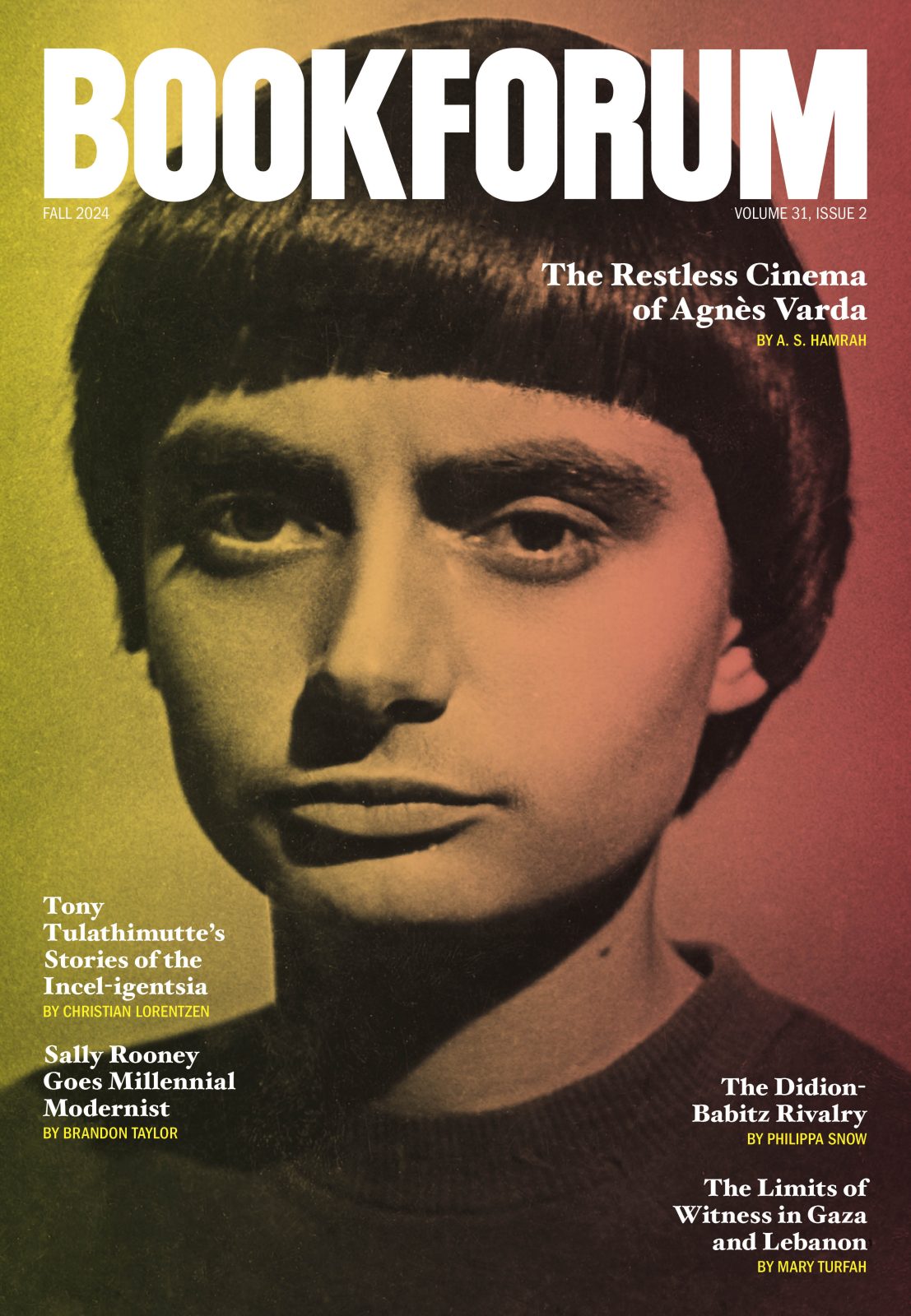

This is a dramatic sensibility born of the stage. “I saw the future for myself when I did repertory theater,” the eighty-four-year-old actor writes in his new memoir, Sonny Boy. “These were plays that could change my life; these playwrights were prophets.” Pacino ascended out of primordial theater stock and lacks the practical indifference of the actor trained on camera. He spent his twenties hanging around Greenwich Village, taking acting classes with Charlie Laughton and then Lee Strasberg, and working odd jobs all over the city. Avant-garde café theater shows led to roles in productions like The Indian Wants the Bronx and Does a Tiger Wear a Necktie?, which won him an Obie and a Tony, respectively. He often stayed with friends or had roommates during this time, but finding moments alone had never been a problem. “I would walk the streets of Manhattan, bellowing out [Shakespeare] monologues as I rambled,” Pacino writes. “I’d do it by the factories, at the edges of town, where no one was around.”This early drive to fling language from whatever platform he was given or took grew over the years into a desire to inhabit language fully and transmit its secrets.

Pacino was raised across the pond from his beloved Elizabethan bard, in the South Bronx, by a supportive family that was usually just scraping by. His parents split before he turned two, and his father wasn’t much in the picture after that. His grandfather Vincenzo was a plasterer who, coincidentally, hailed from the Sicilian town of Corleone. His grandmother Kate would regale Pacino with homespun tales in which the boy always featured as protagonist. Pacino’s memories of his mother, who died when he was twenty-two, center on frequent outings to the movies. After seeing The Lost Weekend with her he started taking requests from relatives to imitate Ray Milland’s character, a writer whose alcoholism leads him to the brink of insanity; five-year-old Pacino would “scramble through an imaginary kitchen with a kind of life-or-death intensity,” searching for imaginary hidden booze. “Even at five years old, I would think, what are they laughing at? This man is fighting for his life.”

Pacino’s grown-up passion is for Shakespeare’s Richard III, the bloody tyrant who faces down his demons alone on the battlefield and in dreams (“There is no creature loves me, / And if I die no soul will pity me. / And wherefore should they, since that I myself / Find in myself no pity to myself?”). The role of King Richard accords with Pacino’s misfit pantheon, but his obsession is really with the play as a whole. So much so that he spent four years making a wonderfully nimble film about the play called Looking for Richard (1996). In Sonny Boy, Pacino writes that Michael Mann let him use some of the crew from Heat to shoot part of it. Pacino wears many hats in his film: actor, director, location scout, and educator. (Not to mention a backward baseball cap that says “Scent of a Woman” on it.) At table reads, he debates the finer points of his character, but he also has much to say about Buckingham, Lady Anne, and the rest. He conducts interviews with actors, academics, and random New York City pedestrians (“This guy is rich, he’s a king, and he needs a horse”). The energy Pacino has for Shakespeare’s play, unleashed in this barely two-hour film, is boundless. One feels he would like to play every part, commune with each of Shakespeare’s words.

Early on in the memoir Pacino muses, “right now as I write this, I’m ratting on myself.” But this is not his book’s actual effect: there is no revelatory gossip, and it’s difficult to spot anecdotes that haven’t been reported elsewhere. The details tend to be fairly anodyne. One section begins: “Of course, there’s the general belief that I’m a cocaine addict or was one. It may surprise you to know I’ve never touched the stuff.” There are honest assessments of disappointing film choices that are so succinct as to be indistinguishable from languid Letterboxd commentary. “I did 88 Minutes, which was a disaster,” Pacino writes. “And then I did Righteous Kill with Bob De Niro, which was not good.” There is little in the memoir about his romantic life and less about his four kids, which is what one would expect from the notoriously press-shy actor. He continues to choose dignity and courts no controversy. There were many grievous setbacks in Pacino’s early life, beyond the deaths in his family. By the early 1970s, the actor had lost his three closest childhood friends to drug overdoses.

Occasionally Pacino is candid, and tender, about these tragedies, but his is never the story of talent triumphing over adversity to scale the heights of stardom. It is the story of an actor with almost no common sense moving inexorably toward a dream. The moments in his book that feel like Pacino is actually fessing up to something are those that refer to his infatuation with the theater. On the joys of performing a Strindberg play off-off-Broadway in his twenties, Pacino is mystical, ardent: “A door was opening, not to a career, not to success or fortune, but to the living spirit of energy.” Without really understanding the spirit, he trusts it, even devotes himself to it. He lets the spirit come to him. “I’ll never learn,” he writes, “and that’s my problem. Or my gift. I don’t learn things.” Better not to know, however much one prepares for a role, to remain open to the mishaps and breakthroughs that strike, like visions, in the heat of performance. Pacino reaches for his William Blake: “If the fool would persist in his folly he would one day be wise. That’s what moves me.”

The creative intuition that served Pacino well in his acting career did his bottom line no favors. He was wildly generous with friends, had a crooked accountant, and went through periods of financial insolvency. When it came time to decide whether to star in The Godfather III, Pacino did not hesitate to accede, on account of being flat broke. Of a family vacation to Europe in 2011, he writes, “I knew I spent a lot of money because I brought my kids, their nannies, and a couple of other people from LA to London and Denmark and back to LA on a gorgeous Gulfstream 550.” He may have lost a small fortune, but the logical progression of this sentence is just so winning. Fame and fortune are useful for flying your kids to Legoland and booking epic roles, but they don’t hold much interest for Pacino. All that superficiality and fuss can get in the way of life. He quotes Iago, from Othello: “Reputation is an idle and most false imposition, oft got without merit and lost without deserving. You have lost no reputation at all, unless you repute yourself such a loser.”

But back to that dream Pacino persists in stumbling toward. “The thing about acting is, you don’t really do it and yet it’s real,” he writes. “That’s the phenomenon. That’s the paradox.” Well, those lines didn’t totally land, let’s go again. Acting, if you’re Al Pacino, is about trying things out, finding new ways to say the old words, seeing something surprising in them and then projecting that discovery with your body, your voice. Ensuring that words are never divorced from their meanings and always remain the incorruptible source of inspiration. The most indelible illusions come from everyday stuff like having too much energy, making happy mistakes, and repeating one’s lines until they’re second nature. You get to carry Shakespeare, O’Neill, and Chekhov around in your head—that’s fun. You can conduct imaginary conversations with your long-dead idols; in Sonny Boy, Pacino recounts how he and Brecht, both “slightly high” and perched on a “love swing,” decide that one of life’s greatest problems is that it lasts too long.

Evidently, one has many experiences as an actor that are incommunicable, or at least not directly communicated. But this is not so isolating as it may seem. Pacino has come close to articulating the waking dream that is live performance—just not here, with his blunt attempts and mania for quoting his heroes. It was with an off-the-cuff anecdote he told during a 1979 interview with Playboy magazine:

The time I was doing [The Basic Training of] Pavlo Hummel in Boston, I made [a] connection with a pair of eyes in the audience and I thought, This is incredible, these eyes are penetrating me. I went through the whole performance just relating to those eyes, giving the whole thing to those eyes. I couldn’t wait at curtain to see who it was. When curtain call finally came, I looked in the direction of those eyes and it was a seeing eye dog. Belonged to a blind girl. I couldn’t get over it—the compassion and intensity and the understanding in those eyes . . . and it was a dog. What a profession!

Hannah Gold is a writer in New York.