Stamps, photographed by Heiji Shin at the Fales Library and Special Collections at New York University, New York, 2023.

ON JANUARY 31, 1975, a twenty-year-old man approached the main entrance of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, took off his jacket and shirt, threaded a steel chain through the door handles, then looped it around his wrists and locked it. On his back, stenciled in black, were the words:

when i state that i am an anarchist, i must also state that i am not an anarchist,

to be in keeping with the ( – – – – ) idea of anarchism

long live anarchism

There to see the Biennial, visitors were flummoxed—they didn’t know what was happening or how to get in or out of the museum. Crowds grew thicker on both sides of the door. The man remained composed, even conversing with some of the patrons, until security guards descended with a folding screen to hide him from view. After forty minutes or so, the man quietly produced a key from his pocket, freed himself, put his clothes back on, and walked away.

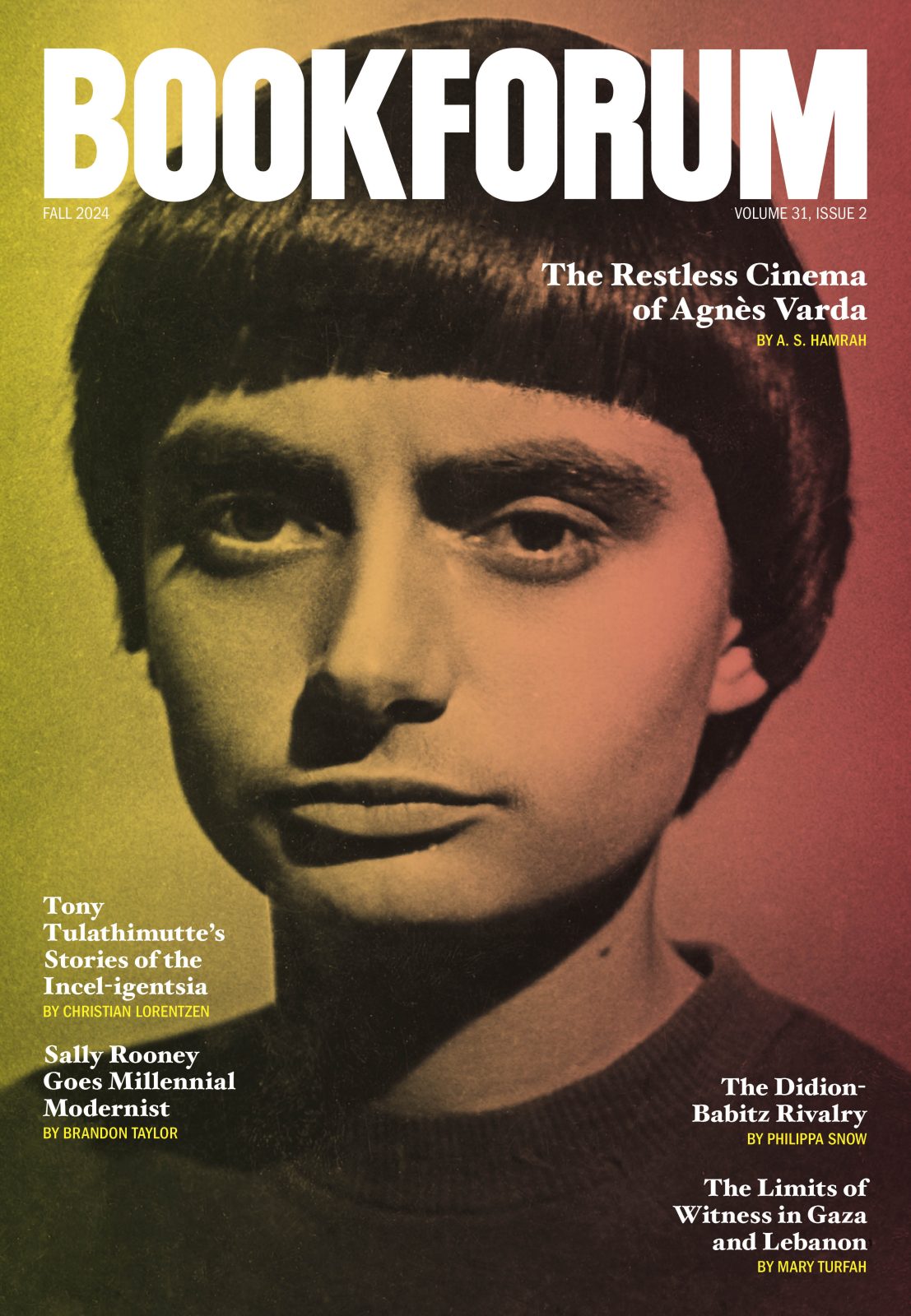

Christopher D’Arcangelo is the highly anticipated monograph of the artist whose work has largely been the stuff of legend, circulating via word of mouth and the occasional exhibition. Though D’Arcangelo is considered an essential figure in the emergence of Institutional Critique—which dissects the structures, systems, and contexts in which artworks are presented and supported (or not)—his absence from the record isn’t wholly surprising. The seven “unauthorized performances” for which he is probably best known, conducted at the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Louvre, and others, left no traces. All that remains are the materials now preserved in the artist’s archive: photographs as well as film and video footage shot by Cathy Weiner, D’Arcangelo’s partner; diaristic accounts of the performances written by the artist himself; correspondence, arrest records, notes, sketches, proposals, objects, and more. Any live event is a kind of disappearing act—now you see it, now you don’t—which perfectly suited his inquiries into the visibility and invisibility of artists, art, looking, and labor.

D’Arcangelo was very clear that these documents were not to be confused with, nor stand in for, his work, but rather to serve as proof that the art existed. Deftly edited by Yana Foqué and Isabelle Sully, this entrancing volume presents selections from his archives, surveying D’Arcangelo’s brief time as a working artist while allowing something of his voice and temperament to come through. (The artist took his own life in 1979 at the age of twenty-four.) Contributions by his former employer, artist Daniel Buren; his friend Louise Lawler; collaborator Peter Nadin; and texts by Jay Sanders (Artists Space), Nicholas Martin (the Fales Library, home of D’Arcangelo’s archives), and others help make his once-mythical life far more vivid. The book also clarifies how devoted he was to dissolving art’s demoralizing hierarchies. He conceived his (unrealized) Open Museum to welcome the art and actions of anyone who wished to share or show their work, a gesture both monumental and humble. As he wrote, “We all do things in our own little way.”