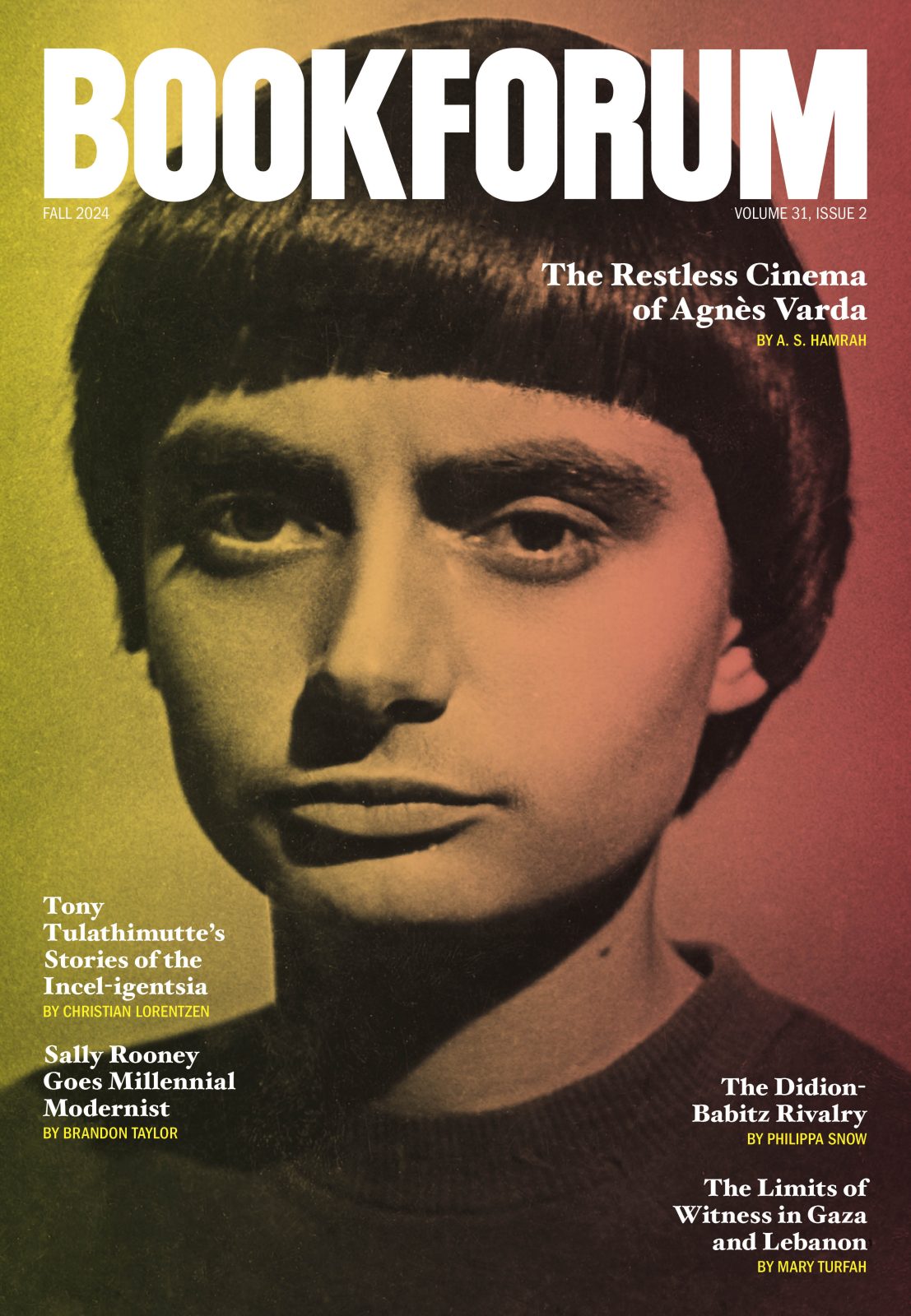

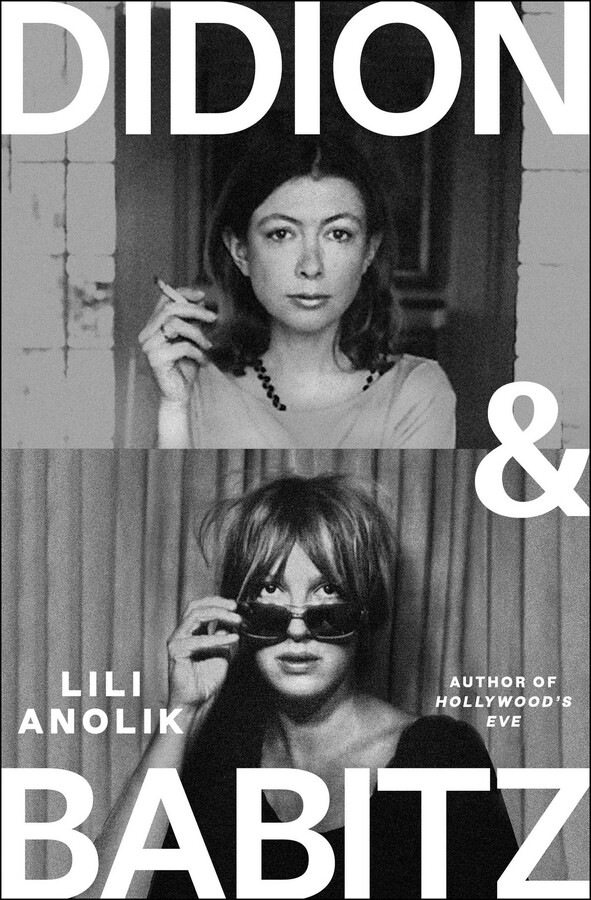

PICTURE, IF YOU WILL, Joan Didion sitting on the floor of a Los Angeles recording studio in 1968, gazing up at Jim Morrison of the Doors, a band she went on to describe as “apocalyptic missionaries of sex.” If our patron saint of Californian disenchantment ever appeared starstruck, even girlish, it was surely here, in the presence of the Lizard King. (“An attempt to cast a spell,” she once called her use of repetition as a literary device. That the phrase “black vinyl pants” occurs three times in her vignette about the Doors tells us all we need to know.) Also in the studio that day were, Didion writes, “a couple of girls,” and of those “couple of girls,” one was the writer and adventuress Eve Babitz, an ex-lover of Morrison’s who was not quite as enamored of his cod-shamanic shtick. The Doors “had lyrics you could understand about stuff [kids] learned in Psychology 101,” Babitz wrote in 1991 in Esquire, an eye roll detectable in print. Didion claimed to like the Doors because “their music insists that love is sex and sex is death and therein lies salvation.” Babitz did not think that love was sex or sex was death, only that sex was sex, and having peeled off those black vinyl pants for herself, she’d seen too much of the man to buy the myth. Imagine calling your most self-serious ex an “apocalyptic missionary of sex” with a straight face. As Didion herself would say: does not apply.

“It was Eve, by the way, who set up the meeting” between Didion and Morrison, Lili Anolik reveals in Didion and Babitz. Anolik is a podcaster and contributing editor at Vanity Fair who is best known for reintroducing Babitz to the culture in a 2014 essay for that publication, after tracking her down as an elderly recluse and bonding with her in the last years of her life. She describes her relationship with Babitz—which yielded her first book, the freewheeling 2019 biography Hollywood’s Eve—as “unbalanced,” even “fetishistic.” Didion and Babitz is inspired by Anolik’s discovery of an unsent letter to Didion in Babitz’s archive at the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in Los Angeles County (the Huntington acquired Babitz’s archive in 2022) . The letter’s tone, alternately pleading and furious, is one that Anolik immediately recognizes as that of “a lovers’ quarrel.” The two women had a history: Didion first got Babitz published by sending a copy of her story “The Sheik” to Rolling Stone in 1972; in exchange, Babitz added Didion and her husband, John Gregory Dunne, to the long list of dedicatees in Eve’s Hollywood in 1974. Now and then, they socialized, and they seemed to be, in modern parlance, casual “frenemies.” This letter, a magnificent document that is among the best things Babitz ever wrote, suggests a more intense connection, and its passion reignites Anolik’s interest in her former friend and subject.

It is easy to see why: Babitz, full of piss and vinegar, berates “sharp, accurate journalist” Didion for her inability to talk about “art. Vulgar, ill-bred, drooling, uninvited Art.” It is a full-throated statement of intent from a big-brained babe who, however louche she seemed when she wrote for her public, saw herself as a committed Woman Artist. “It was back. My love for Eve’s astonishing, reckless, wholly original personality and talent,” Anolik says, overwhelmed and ecstatic. As in Hollywood’s Eve, Anolik’s voice in Didon and Babitz is fizzy, conversational, sometimes faintly loopy, as if you are being given a piece of gossip by a person who is certain it will blow your mind. She is also a self-confessed square, and this squareness gives her interest in her subjects—Babitz in particular—some of its squirrelly charge. Her aim here is to position these women as each other’s inverted mirror images: fastidious, frigorific, bony Joan, and heedless, hot, voluptuous Eve. “Each was the closest the other had,” she proposes, “to a soul mate.”

Ultimately, both were skilled documentarians of life in 1960s and ’70s Los Angeles, even if the lives in question happened to be fueled by different substances. Then again, perhaps not: “The drugs [Joan] was on,” Babitz tells Anolik, “I was on. She looks like she’d take downers, but really she’s a Hells Angel girl, white trash.” (Eve is talking, clarifies Anolik, about speed, although if the reader is not a self-identifying square, they might already have guessed.) Didion and Babitz is full of these minor, unexpected crossovers between its subjects, and one of them is that scene in the studio with the Doors, which Anolik sees as a key to understanding their respective sensibilities. In The White Album, Didion fixates on a gesture of Morrison’s: the lowering of a lit match to his fly. Babitz tells Anolik that, in fact, he was flicking the flame in Joan’s direction: “He was flirting.” Deeply engrossed in the theater of it all, Didion ends up missing out on the real action. Contrast this with Babitz, whose writing is characterized less by the acuity of her observations than by the gloriously shameless heat of her desire—for food, for life, and for fuckable men. “Joan took Morrison,” Anolik says, “at his persona.” Eve merely took him out for a spin.

This three-way psychodrama in the studio is compelling precisely because it is, in effect, a snapshot of three individuals with big, singular personae facing off against each other. The question of what we gain or lose by taking icons at face value is a crucial one throughout Didion and Babitz—not for nothing did Norman Mailer, in 1965, describe Didion as “a perfect advertisement for herself,” and Babitz’s bimbo-genius act may have seemed artless, but as that letter proves, it was just that: an act. In her introduction, Anolik reveals that she is nervous about dissecting Didion, before asking a favor of the reader: “Don’t be a baby.” It’s a bet-hedging move that anticipates a flurry of indignant Goodreads reviews, and given Didion’s popularity with people who wear pictures of authors on their tote bags, Anolik is right to be concerned. On the other hand, I must admit that historically, I’ve been something of a baby myself when it comes to Anolik’s writing about Babitz, whom she tends to portray with a mixture of dizzy adoration and brutal honesty. In Hollywood’s Eve, she calls the older Babitz “a ruin and a gorgon,” and both books apply a flurry of stomach-churning adjectives to Babitz’s trash-filled apartment. Stripping a woman like Babitz of her glamour feels to me like a betrayal, and reading about her smelling of “decay” is like seeing her the wrong kind of naked (as opposed to the right kind—that is, when she’s playing a game of chess against Marcel Duchamp).

I prefer to see Babitz the way Didion saw Jim Morrison, with her persona intact: as an ecstatic “missionar[y] of sex.” Charisma is, however, an enchantment that is best maintained at a distance, and Anolik has been close enough to Babitz to peel off her vinyl pants, if only figuratively speaking. About two-thirds of Didion and Babitz is, well, and Babitz. Less fleshed out by far is the material about Didion, whom the author did not know, and admires somewhat less. In addition to this bias, says Anolik, Didion in general is “opaque enough, elusive enough, withheld enough, far-fetched enough, that she’s almost a ghost.” The image of Didion that emerges here is the one you might expect: that of a woman whose appearance of shyness was half real, half strategic, and whose work—which she composed carefully, rhythmically, like an orchestral arrangement—was the most important thing in her life. When Anolik bemoans the fact that people “get a little soft in the head” and “go teary-eyed at the thought of [Didion’s] wifehood, her motherhood, her widowhood, her bereft-motherhood,” I had to wonder: who, exactly? In my experience, Didion is usually loved for her chill, almost evil-seeming precision—not for her domesticity. (Perhaps it is those tote-bag carriers again.) Truthfully, I could have done without the book’s attempts to out Dunne as gay, but more for reasons of taste than because of my need to believe in the sanctity of the famed Didion-Dunne marriage, which like all marriages presumably had its own private set of rules.

The other big revelation in Didion and Babitz is the identity of Didion’s first love, a writer named Noel Parmentel Jr., who was immortalized as three separate characters in her novels, and who tells Anolik he “invented Joan Didion.” Certainly, there is no doubt that his promotion of Didion’s work in literary circles helped her move out of Vogue and into “serious” publications. Still, as with preferring to remember Babitz in her pomp, I prefer to think of Didion as the inventor of Joan Didion. Either way, there is that idea again—that of an icon being something constructed. “Joan and Eve are the two halves of American womanhood,” Anolik concludes. “The id and the superego, light and dark, sex and death.” No woman, of course, actually embodies only one of these extremes, unless she happens to be doing so deliberately to make herself into a work of art, “ill-bred” or otherwise. By the end of the book, one feels a shift in the author’s image of Babitz, even as Didion remains out of reach. If Hollywood’s Eve saw her as a “lewd angel,” here Anolik is ready to see Eve as a real “Bride of Art,” just as canny and as calculated as her “secret twin.” Being around Babitz in real life seemed to negate some of her magic for Anolik; in Didion and Babitz, the author’s realization that she might have known “the wrong Eve” all along recasts the spell. There is a third way to react to a persona: to appreciate it for the work its maintenance requires. Doing so is a form of respect, perhaps even an expression of love. What is it they say on social media? “A crush is just a lack of information.”

Philippa Snow is a critic and essayist who lives in England. Her last book, Trophy Lives, was published by Mack in 2024.