RIOTS IN PARIS GRAB THE HEADLINES, but the real radicalism in France happens in the countryside. Take the zone à défendre, or ZAD, in Notre-Dame-des-Landes. What began in 2012 as a farmer’s protest against the construction of an airport turned into a successful squatter campaign that drew allies from environmental and anarchist groups across the country. Over the course of six years of living and protesting together, the zadistes built an autonomous village in Notre-Dame-des-Landes that included food-production and -preparation facilities, waste disposal and washing areas, a library and a radio station, a brewery and a bar. In her recent collection of essays and interviews The Politics and Poetics of Everyday Life, Kristin Ross, who specializes in the history and sociology of the “commune-form” going back to the Paris Commune of 1871, described the ZAD as a “political experiment in living.” According to Ross, the aim of twenty-first-century communes is to create “pragmatic alternatives” to neoliberalism and the nation-state “in the here and now,” not in urban space but “in the interstices of capitalist logic, the zones it forgot.”

Or take the more notorious case of the Tarnac Nine, who set up a similar commune in Limousin a few years earlier. Along with communal living, the group is believed to have engaged in the disruption of a TGV train network and other forms of industrial sabotage. The group is also thought to have written, under the collective pseudonym the Invisible Committee, a manifesto called The Coming Insurrection. A staple of leftist bookshelves following the 2008 financial crash, The Coming Insurrection—which concludes with the slogan “All power to the communes!”—gained a wider audience in the United States when the now-forgotten conservative hyperventilator Glenn Beck called it “quite possibly the most evil thing I have ever read” on his Fox News show. The Tarnac Nine dispersed following the arrest and trial of its members, who were acquitted of all the main charges, but politically motivated attacks on the TGV network continue to this day, with the most recent occurring hours before the opening ceremonies of the 2024 Olympics.

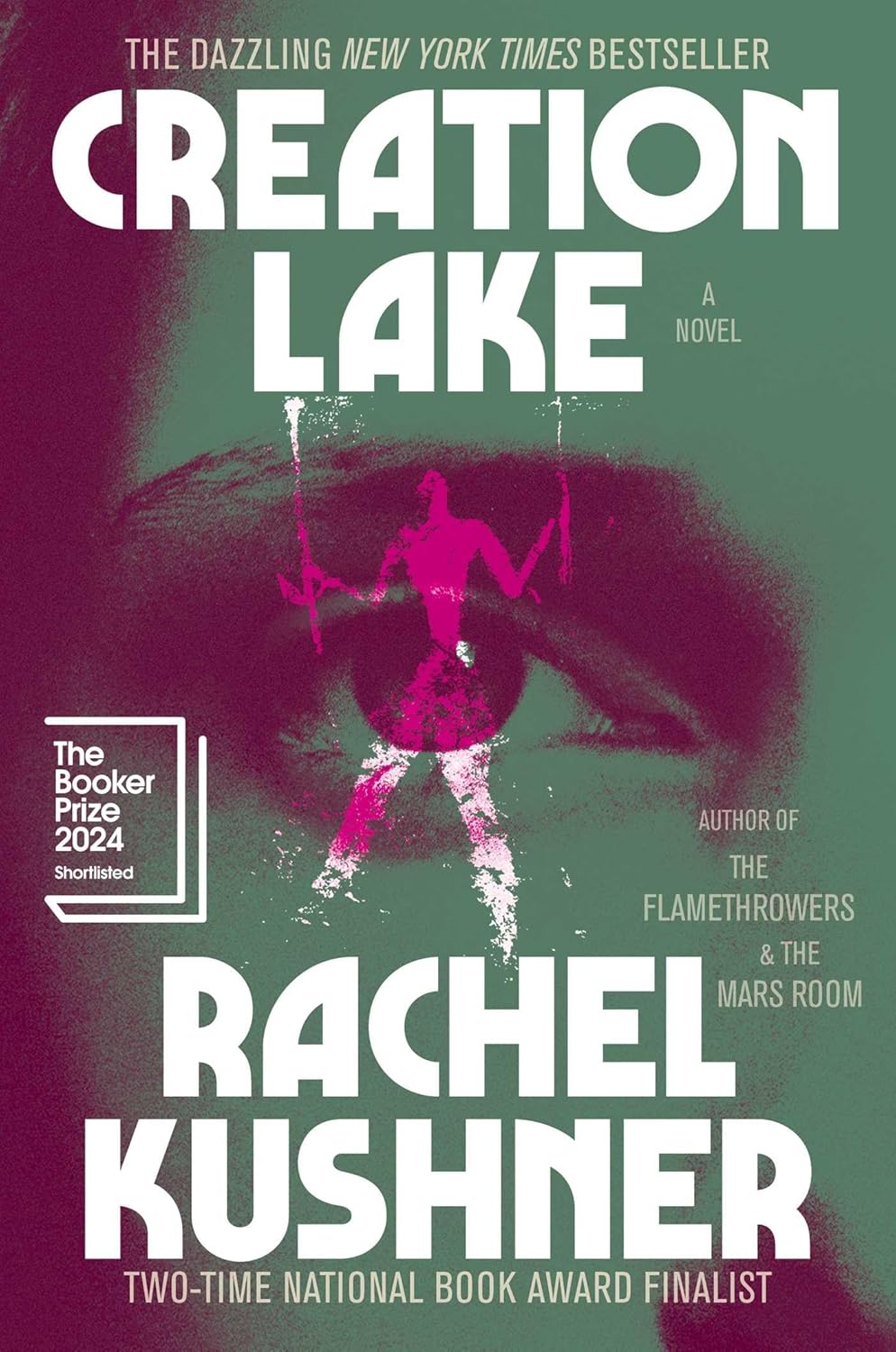

Groups like these form the inspiration for Le Moulin, the agrarian anarchist commune at the center of Rachel Kushner’s Booker-shortlisted and National Book Award–longlisted fourth novel, Creation Lake, set during the summer of 2013, the year no ear could escape the worm of Daft Punk and Pharrell Williams’s chart-topping single “Get Lucky,” and the world learned that no metadata could escape the eyes of the National Security Agency’s PRISM program. Kushner has shown a consistent interest in the politics of parallel societies, from the expat community living in Havana on the eve of the revolution in Telex from Cuba, to the downtown New York art scene and the Italian motorcycle factory of The Flamethrowers, to the women’s prison in The Mars Room. With Le Moulin, whose forty-five inhabitants tend eleven hectares of land outside the fictional village of Vantôme in the Guyenne region of southwestern France, she turns her full attention, for the first time, to the interpersonal dynamics of an explicitly political intentional community.

Having recently destroyed a fleet of tractors, Le Moulin is suspected of planning further sabotage to halt the building of a megabasin that would transfer water from local farmers to corporate agricultural concerns and destroy Guyenne’s unique network of caves. Our window onto their activities is a thirty-four-year-old American, alias Sadie Smith, who has forgone graduate study in rhetoric at UC Berkeley to pursue a more exciting and lucrative career as an agent provocateur for the FBI. Following a botched job in Oakland, where a court rules that her attempt to get two environmental activists to commit ecoterrorism constitutes entrapment, she takes her foreign-language skills, expertise on left-wing social movements, and understanding of “how those movements can be destroyed, either from outside or inside,” to clients in the European private sector.

Her mission, revealed in stages over the course of Creation Lake, is to provoke a police raid of the commune by encouraging the Moulinards to assassinate the far-right politician Paul Platon, a deputy minister in the Ministry of Rural Coherence. This serves two purposes: to eliminate the commune and at the same time Platon, who has irritated her corporate employer (and maybe also French intelligence). Sadie’s first move is to seduce Lucien Dubois, an effete, upper-class filmmaker, whom she meets in a Paris bar “playing pinball in a fedora like he thought he was in a French new wave film from 1963.” Then she gets Lucien to introduce her to his childhood friend Pascal Balmy, a veteran of the anti-globalization protests in Genoa, a suspect in the 2008 bombing of an army recruitment center in Times Square, and Le Moulin’s de facto leader. While Lucien is on set in Marseilles, filming an adaptation of what sounds like a novel by Jean-Patrick Manchette, Sadie infiltrates the group by offering to translate their Invisible Committee–esque manifesto, Zones of Incivility, into English.

To paraphrase Rick Blaine’s description of Captain Renaud in Casablanca, Sadie is a typical Kushner character, only more so. Like Reno in The Flamethrowers, she knows her way around mechanical devices and combustion engines; a motorcycle appears on the first page of Creation Lake as if it were the gun on the wall in Chekhov’s famous maxim. Like the intriguer and burlesque dancer Rachel K in Telex from Cuba and the street-smart stripper Romy Hall in The Mars Room, Sadie is unsentimental and transactional about romance and sex, which is sometimes an unpleasurable drawback (as when she has to go to bed with Lucien to keep her cover) and sometimes a fun perk (as when she gets to bang René, one of the Moulinards) of her line of work. She is also an inveterate explainer of the way things, people, and places work, the product of a writerly imagination that likes to leave as little of her meticulous research—whether it is into the United Fruit Company, Brazilian rubber manufacture, prison moonshine production, or pseudoscientific Japanese blood-type personality theory—on the cutting-room floor as possible.

In Creation Lake, Kushner reduces the multiple narrative perspectives of her previous novels to a single first-person narrator. Espionage is an ideal profession for such a narrator to have. Believably partial (in accordance with standpoint epistemology) and believably omniscient (in accordance with surveillance capitalism), the spy is a worthy successor to that defunct three-letter agency, God. But with hard-boiled Sadie, Kushner dials up the cynicism to eleven. She makes Sadie so ostentatiously unlikable, it is as though she were less interested in creating a believable character than wading editorially into the debate that surrounded Nora Elridge, the protagonist of Claire Messud’s The Woman Upstairs, published in 2013, the same year as the events recorded in Creation Lake.

Sadie is indiscriminate in the objects of her contempt and condescension. The scare-quoting female grad students of Berkeley, whose fingers she imagines slicing off, and beta male Lucien arguably deserve it; the French language, landscape, and cuisine do not. (Balzac, Flaubert, and Zola are, thankfully, spared.) The list of things Sadie pointedly claims she “do[es] not care” about is quite long. It includes food, art-house cinema, swindling cabdrivers, the Guyenne region, what people do, other people’s things, her rental car, Paul Platon, and Lucien’s affair with his location scout. Her “expensive” boob job is brought up often enough that the detail begs to be read as a symbol of the fundamental fakeness and hollowness of her character. Sadie may fancy herself to be an antihero, but really she is a midlevel girlboss, who enjoys a bottle of white wine, a piece of gossip, and a good hard fuck as much as the next person, but whose truest pleasure is ruining people’s lives for money.

There are, of course, literary pleasures to be had in a sociopathic protagonist. However, unlike the more ingenuous and self-doubting anthropology grad student who travels to Botswana to join Nelson Denoon’s matriarchal commune in Norman Rush’s Mating, Sadie’s cynicism inoculates the reader of Creation Lake against running the risk of falling under Pascal’s spell, confusing the society the Moulinards have built with utopia, or considering its members to be a genuine threat to the national security of France, let alone capitalism. As with most intentional communities, there is a wide gap between theory and praxis at Le Moulin. In the role of charismatic leader, Pascal plays to type; he expels his critics, puts his trust in the wrong people (such as Sadie), and has two children with a fellow Moulinard, who returns with them to Paris. The gendered division of labor persists: women do most of the work in the “communal” crèche and kitchen. As does the division between intellectual and manual labor: the well-educated Alexandre and Jérôme spend more time in the library engaged in theoretical discussion and literary work than in the woodshop with René, a former factory worker from Alsace, and Burdmoore, whom readers of The Flamethrowers may remember from his deadly hijinks with East Village anarchist collective the Motherfuckers. “Refined and Parisian,” Alexandre turns up his nose at the lower-class white Catholic farmers of Guyenne, whom he thinks of as uncultured bigots. An experiment in child-directed education is brought to an end when an eleven-year-old fathers a child with his teacher.

Sadie rolls her eyes at the Moulinards for quoting Fredric Jameson’s maxim that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, but surely it is the task of a novelist who has taken an anti-capitalist movement as her subject to try, if only for the sake of dramatic tension. After all, if the narrator does not find Le Moulin worthy of caring about, why should the reader? Because the destruction of what Sadie dismissively calls “their little commune” is a fait accompli, Kushner is forced to downgrade the stakes of Sadie’s mission from impinging on “the future of France” to something more familiar and therefore less satisfying: the swatting away of a few dozen pesky idealists who threaten to momentarily interfere with the profit margins of their betters.

If anything, what distinguishes Le Moulin from other leftist movements, real and fictional, are the outlandish theories of its guiding intellectual, Bruno Lacombe, the most novel and therefore the most interesting part of Creation Lake. The son of a French Communist father and an Odessa-born Jewish mother, who were members of the Resistance and perished in the Holocaust, Bruno is sent to safety in the South of France, where he spends a feral childhood in the company of a roving band of boys orphaned by the Nazi occupation. A hoodlum and petty criminal, adolescent Bruno makes his way to Paris during the heyday of café existentialism. There he meets Guy Debord, the founder of the Situationist International and the future author of The Society of the Spectacle, who takes him under his wing. Following the failure of May ’68, both decamp to the countryside in disappointment. Debord drinks himself to death as he did in real life; Bruno teaches at a reform school, writes his major work Leaving the World Behind, marries and has three children, and buys a small plot of land not far from the decaying manor of the Dubois family, which Sadie will later make her base of operations. Following the tragic death of his youngest daughter in a tractor accident, he retreats into the cave network he discovers beneath his house. From there he sends emails explaining his political, ethical, and anthropological views to his Debord-obsessed acolyte Pascal, the other members of Le Moulin, and, unbeknownst to him, the American spy who has hacked his account, and transmits his emails, in her translation, to the reader.

“The trick of riding backward,” Sadie remarks during a TGV ride to Marseilles with a queasy Lucien, “is to understand that this orientation of travel is time-honored and classical.” One often noted feature of post-’68 leftism is the abandonment of grand narratives of progress, rooted in a secularized theology shared by enlightenment liberalism and Marxism alike, in favor of a more pessimistic outlook toward the future. Many leftists today could be described as restorationists who “enter the future backward” like Sadie’s train and Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History. This account of history is no less theological, since it includes a “Fall” into conditions of domination, immiseration, exploitation, and despoliation. For some, the Fall is as recent as the collapse of the Soviet Union or the neoliberal revolt against postwar social democracy. Others point to an earlier moment: the opening of a global market through imperial conquest, the development of the factory system, the enclosure of common land into private property, the invention of currency, or even the founding of sedentary society itself, which introduced such ills as the patriarchal family and the state. In each case, the goal is to restore the political conditions of the prelapsarian past.

No mere “anti-civver” or “primitivist” critic of the state, capitalism, and technology, Bruno locates the Fall still further back, in prehistory, when the noble Neanderthal was violently displaced and superseded by the cunning, tool-making, fraudulent Homo sapiens. Contrary to scientific consensus, the “Thals,” as he affectionately calls them, did not go extinct, as one can see from the persecuted Cagot who lived in Guyenne during the early modern period and more contemporary phenomena such as the Yeti or Bigfoot “myth.” Bruno argues that every living human being is really an Indigenous Thal whose genome is under occupation by Homo sapiens DNA. Like a psychoanalyst, Bruno hopes to help people recover awareness of their repressed Thal “essence” locked away in 2 to 8 percent of their genome and to teach them how to recover such skills as cave-dwelling and hand-fishing.

By the time Sadie arrives on the scene, the Moulinards have lost patience with Bruno. “At first we all got kind of sucked in,” Jérôme admits. “But when you pull away, it starts to seem like madness.” Bruno’s theories are crankish and easy to poke holes in. For one thing, he communicates them using a modern communications technology. For another, if Neanderthals were an objectively superior species, they would not have been supplanted by Homo sapiens. And, anyway, what use could a person have for the view that the thing that is standing in the way of improving social and economic conditions is the genetic makeup of his species?

Read symptomatically, however, they capture something important, not about the politics of Bruno’s country, but of Sadie’s. Until recently, you could describe mainstream American politics, as George Scialabba has, as a conflict over modernity. Progressives have argued that the aim of politics, following Martin Luther King Jr., is to bend the moral arc of history toward justice; conservatives, following William F. Buckley Jr., have argued that its aim is instead to “stand athwart history, yelling stop.” In the eleven years between the events of Creation Lake and the novel’s publication, conservatives appear to have won the argument. With a future foreshortened by expectations of imminent climate doom, and a widespread pessimism about the possibility of the democratic reform of advanced industrial capitalist states—to say nothing of their revolutionary overthrow—ideological conflicts have come to take the form of disagreements about precisely at which moment history ought to stop. And this is no less true for ideologies outside the narrow spectrum of opinion permitted in the United States by what the French like to call l’extrême centre composed of both progressives and conservatives—from online tankies and trads to degrowth communists and neoreactionary monarchists—as it is for the current Democratic nominee for president, whose “we are not going back” slogan, reminiscent of the vapid rhetoric of the first Obama administration, is not quite equivalent to “we are going forward.” By reframing the debate about political orientation toward history not in terms of the value of modernity or even of civilization, but in terms of the species itself, what Bruno inadvertently provides is a reductio ad absurdum of restorationist theologies of the left, right, and center.

Surprisingly, despite some initial misgivings, the one person who comes to take Bruno’s ideas seriously is Sadie. Perhaps that’s because they chime with one of her own pet theories, which Kushner, in a recent interview with The Drift, endorses. “There is no politics inside of people,” Sadie believes. Rather, the “deeper motivation” of their “rhetoric”—their values, their opinions about political issues, their theories about how society works and should be organized—is to “shore up their own identity” and “protect their ego.” When you strip away their political views, she says, every person has a “four a.m. self,” a core “substance that is pure, stubborn, and consistent,” not unlike the Thal essence that Bruno believes lies in every person. Sadie calls this essence their “salt.”

There is, pardon the pun, a grain of truth in this claim. We tell ourselves stories in order to live, after all. If that seems self-evident in the case of a narrative genre like the novel, it is no less the case for a discursive genre like theory. Bruno’s theories, for example, are elaborate but transparent attempts to rationalize his personal sorrows: after the failure of May ’68, he rejects the urban in favor of the rural; after his daughter’s death in the tractor accident, he rejects agriculture; and so on. But skepticism about the sincerity of people’s political motives tends to be fired in only one direction: at critics of the social order by those who uphold it. The reason for this is that those who would like to change the social order must explicitly articulate their criticisms of it, which then read as political or ideological, whereas those who uphold the status quo are allowed to presume that their views are natural or simply go without saying. In fact, the real mystery is the deeper motives of the people who identify with a social order that oppresses them and exploits them, and controls them so completely that they are unable to see that their compliance with it is very much a political activity, indeed the most widespread form of politics there is.

So what of Sadie—she of the fake name, the fake place of birth, the fake jobs, the fake relationships, the fake breasts? What is her four a.m. self, her salt? Is it that her fear of personal commitment—she always wants “the option of doubling back, reversing course, changing plan”—extends to political and ethical commitments as well? Has she really been persuaded by Bruno, or do the things they have in common—she has the same blood type as the German soldier in one of Bruno’s stories, both are practiced thieves, and she is the exact contemporary of his dead daughter—suggest that all along she has just been in search of a surrogate father? Anyway, isn’t the view that political convictions are merely screens for egotistical drives just the sort of thing a corporate spy—one, moreover, who is the first-person narrator of a novel—would say?

In the same Drift interview, Kushner remarks: “The novel as a form is not an occasion for taking a political position.” This is also true but only trivially so. Because of the gap between the author and the narrator, the novel form is fundamentally ironic, and does not, unlike a treatise or a manifesto, “take” a “position” on anything, even if certain characters in it do. From this, however, it cannot be inferred that the particular formal choices an author makes about literary genre, narrative perspective, character, plot, and so on, do not have, at a very minimum, latent political content. Sometimes the more complexly ironic a novel is, the more usefully it expresses the ruling ideologies and political contradictions of its era, which is why no less an authority than Friedrich Engels, in one of his few statements about Marxist aesthetics, counterintuitively claimed that, for the left, “one Balzac is worth a thousand Zolas.”

We have just seen, in the case of Creation Lake, how Kushner’s choice of narrative perspective and character have the effect of disaggregating a collective into its component individuals and reducing political convictions to personal interests. We should add that these are political outcomes baked in to the literary form of their representation, not into reality itself. The charge that Sadie levels at Lucien and that Bruno levels at Pascal—that their respective attachments to ’60s- and ’70s-era figures like Godard and Debord are forms of nostalgia and romanticism—could also be leveled at Creation Lake, which reads like a literary-fiction adaptation of the aforementioned Jean-Patrick Manchette, whose Debord-influenced crime thrillers about female assassins, anarchist collectives, undercover cops, and political demonstrators were written half a century ago, in the early years of the neoliberal counterrevolution. In other words, Creation Lake may describe a period of political restorationism, but is itself an instance of aesthetic restorationism. As such, it not only formally mirrors the political impasses of its own time, it reproduces them. It may be easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, but it is no less difficult, it seems, to imagine a new form for the novel. Perhaps these two difficulties are not unrelated.

The climactic confrontation between the Moulinards and Deputy Minister Platon is set to take place at a local agricultural fair. It will prove to be less tragedy than farce. Platon is traveling light, with his disloyal Serbian bodyguard, and a surprise guest, the French novelist Michel Thomas, a pen portrait of Michel Houellebecq. (Thomas is there to do research for an “agricultural novel”—presumably a reference to Seratonin, Houellebecq’s book about the gilets jaunes, that other, hardly left-wing protest movement to emerge from the French countryside in recent years. As these things go, this is a far funnier literary in-joke than naming a minor character after Don DeLillo Mao II, or, indeed, the main character after the author of, most recently, The Fraud.) Meanwhile the walls have started to close in around Sadie. Her past involvement with the FBI has become a matter of public record, her affair with René has been discovered, and she is drinking heavily.

Sensing that the Moulinards are heading toward catastrophe, Bruno sends one last email from his cave, warning them that violence against property is acceptable, but violence against people is not. He announces that he has discovered a “flaw in his thinking”: his Thal theory suffers from “reverse teleology” and there is no reason to presume that the past was necessarily better than the future might be. He encourages the Moulinards to stop what they are doing and contemplate the grandeur of the night sky. On the eve of the fair, Sadie is the only one who follows his advice. Beer in hand, she steps outside the Dubois manor, looks at the Big Dipper, and has the epiphany that ensures that if she can pull it off, betraying the Moulinards will be her final job. In the end, the real theorist of Creation Lake turns out not to be Bruno Lacombe, but Pharrell Williams: We’ve come too far / to give up who we are / so let’s raise the bar / and our cups to the stars. Sadie is up all night to get lucky. And, reader, she does.

Ryan Ruby is the author of Context Collapse: A Poem Containing a History of Poetry, forthcoming in November from Seven Stories Press.