OVER THE COURSE of two seasons of the TV sitcom Mixed-ish, a spin-off of ABC’s eight-season hit Black-ish, biracial protagonist Rainbow Johnson tries to adapt to regular life after a childhood spent in an idyllic race-blind hippie commune. In episode after episode, innocent Rainbow encounters confusing, contradictory examples of how race operates in the mainstream world of the 1980s. In one, she straightens her hair for school photos, betraying her mother’s sense of Black pride but earning temporary popularity among the other students. The episode begins with a cozy voice-over that places the subsequent events in historical context—“Today the natural hair movement is a celebration that allows women of color to wear their kinky tendrils loudly and proudly . . . but we had to fight to get here, and our hair used to be the tip of the spear.” The message is laid out clearly: one person can’t really resolve all the tensions their racial identity evokes in the world around them, and yet, at the level of laugh track and grand narrative sweep, they kind of can—simply by being themselves! With just the right amount of friction to build character, and the feel-good moments that make it all OK, a vision of race can be achieved that is both colorful and free of harm.

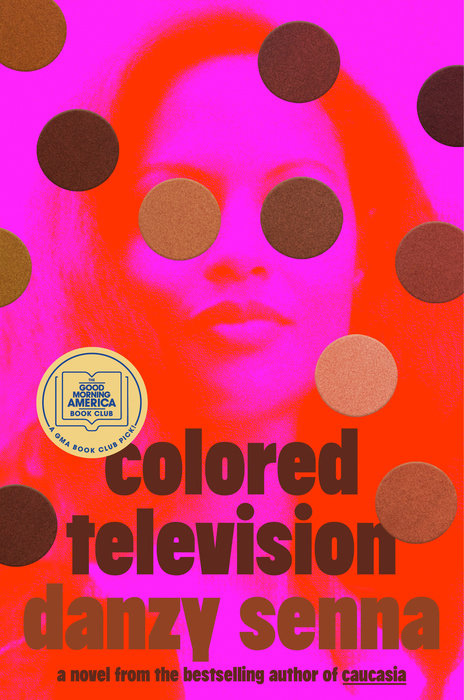

Danzy Senna’s Colored Television, her fourth novel in a career spent cataloguing, decade by decade, the latent possibilities and impasses of mixed-race identity, takes this TV fantasy of breezy reconciliation as its protagonist’s fraught goal. Jane Gibson, a novelist teaching creative writing in Los Angeles, is mired in a cycle of tragic apartments and bougie housesitting gigs that have kept her and her husband Lenny, a struggling abstract painter, in a state of continual upheaval as they try to raise their two kids on adjunct and just-above-adjunct salaries. The chintzy utopia of Hollywood narrative promises relief from her family’s financial woes, as well as from the 450-page “mulatto War and Peace” that is her second novel—a book spanning hundreds of years of Black history and several different narrative perspectives, a book that pays homage to the history of racial passing in Hollywood and the white-passing mixed-race Melungeon community of nineteenth-century Appalachia, a book so ambitious that it has smothered Jane’s own ambition under its considerable weight.

When Jane’s novel is rejected by her editor and sidelined by her literary agent, she decides instead to pitch Hollywood types on an idea for a TV series that her wildly successful biracial friend Brett came up with. Brett also happens to be the owner of the house in which she and her family live their temporarily luxurious life. His concept for a show starring two leads who just happen to be halfies imagines race as something that would pop up every so often as a crowd-pleasing cameo.

He’d said he wanted the fact of them being biracial to be not the subject of the show, exactly, but just something they happened to be—when race came up at all, it would be more of an impetus for humor than something tortured and heavy. In other words, it would be a comedy, not a tragedy, something so punchy and funny that people wouldn’t remember all those old-timey tragedies of yore—the Douglas Sirk of it all—and would only see the future of mulattos, the whole sunshiny vista that lay ahead.

Jane’s pitch—vague as it is, and derivative of a set of tropes so well worn she can’t really be said to be stealing it—attracts the attention of hotshot producer Hampton Ford, who has recently struck a development deal with a television outlet to create “diverse” content that is also highbrow (“that’s so prestige” is a phrase that gets uttered many times over by Hampton and his assistants in their brainstorming sessions). What follows is a plot common to many movies and books about writers who’ve ventured into Hollywood lured by the promise of easy winnings: endless meetings and notes on the promise of success to come, and then, finally, a twisty bit of intellectual property theft that crushes Jane’s dreams while simultaneously offering crucial affirmation of her instinct for story.

Senna’s protagonists are often driven by the longing to choose a side: the plots that ensnare them are generated by the difficulties of making it, securely, from one side to the other. Birdie Lee, the heroine of Senna’s 1998 debut, Caucasia, wants to escape her white mother and the false identities they’ve been living under in small-town New Hampshire, to be accepted as Black despite her passing appearance. In 2017’s New People, multiracial Maria’s romantic obsession with a Black poet she hardly knows wreaks havoc on her trendy Brooklyn lifestyle and her relationship with a similarly multiracial man. Jane, too, wants to choose a side—but after securing the photogenic dream family she once saw in a Hanna Andersson catalogue (rugged Black husband, two cute brown kids), her truest longing is for an upper-class LA lifestyle far from financial precarity, the kind of life those around her seem to be living regardless of their race. But no matter how much Jane wishes to identify as bourgeois, class is one type of identity that cares little for how you identify or declare yourself: your net worth has the final say.

With this sly sleight of hand, Senna deftly scrambles hierarchies of race, class, and culture, leading Jane through an absurdist take on the culture machine, where the dynamics of industry approval are as labyrinthine as the cultural construction of race. Hampton privately bemoans the dilution of Black experience as his inexplicably white-presenting daughter mingles with the mixed children of Kardashians at a birthday party, but he nevertheless works to create content for biracial viewers because it is, in his words, “the fastest-growing demographic in the country.” Jane’s highbrow novel about niche multigenerational experience does not have sufficient mass appeal to interest the publishing industry, and her more commercial pitch for a quasi-utopian family comedy where all conflict is comedic is not sufficiently highbrow for a creator of lowbrow content who hopes to make it firmly into the middlebrow—nor is it in his words “sufficiently biracial.” “I can make it more biracial,” Jane offers in desperation, as Hampton shoots down yet another episode premise. This is a culturally extractive industry, and Jane is expected to help the system mine her demographic, fracking the self for little bits of essential experience that can be processed into a general cultural narrative.

Novels about Hollywood often lampoon the industry while judging the literary writer in a softer, gentler light—writers are fools, but who wouldn’t be corrupted by the promise of so much money and glamour? But Senna does not excuse literary fiction from the ambivalence she extends toward the idea of authentic storytelling as a whole. Which work, Senna asks, was the sellout: the broad, cinematic doorstop of a novel whose multigenerational structure was supposed to help Jane secure the acclaim she needs to pass her tenure review and escape her precarious circumstances? Or the more degraded and audience-pleasing sitcom version, which contains within it a more honest representation of her desires, wishing as she does to be simple, incidental, and aspirational? “They had taken too many of their cues from poets—allowed themselves to become dreary solipsists driven by the prospect of awards,” Jane thinks to herself. “They’d become too swept up in the whole Marion Ettlinger of it all, thinking their writing needed to be as leaden and stone-faced as their author photos.” In the end, it’s the prestige material, the story that reinscribes a certain tragic version of the racial in-between, that proves to be more marketable once it is properly cleansed of nuance and given a sentimental arc. Whether a Twinkie is factory made and wrapped in plastic or crafted artisanally from scratch by a social media tradwife, it still feeds a common craving for the comfort of sugar.

But even if the novel has lost something of its sanctity in Colored Television, it still captures more of the complexities and contradictions of identity. From within Senna’s novel, Jane recalls a scene from her dead-end epic, one focused on the isolated Melungeon community whose light-skinned inhabitants venture into town only to buy necessities, living under the cover story that they are of Portuguese descent in order to escape scrutiny. One night, one of the children calls to his mother, homesick and crying that he wants to go home. “The boy cried in great heaving wails and began to call out for Portugal, a country where he’d never been. The mother stroked the boy’s back and told him to hush, but the boy only cried harder until finally she told him that she missed Portugal too, and that someday, someday, they’d go back.” It is here in this made-up moment, a fiction nestled inside a fiction nestled inside the larger fiction of race as essence rather than the shifty, market-driven thing that it is, that we find the book’s most urgent argument for the necessity of storytelling. A fiction can provide a home that can be cried for, satisfying a need to mourn that is more concrete than the loss itself. It may be a false home—but that doesn’t mean the tears can’t be real.

Alexandra Kleeman is the author of Something New Under the Sun (Hogarth, 2021).