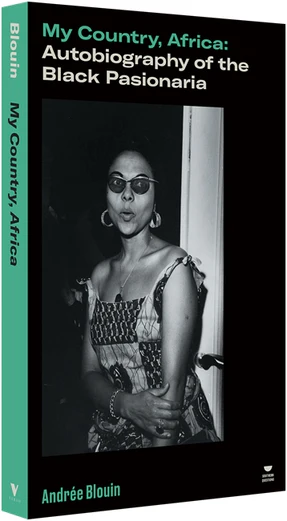

HISTORICAL FIGURES re-emerge into public attention according to a quasi-astrological logic. Before she fell into relative obscurity, Andrée Blouin was a luminary of the African decolonization movement of the 1950s and ’60s—beautiful, glamorous, and gifted with an acute understanding of power. She was in the right places at the right times: she first became politically active in the independence campaign led by Ahmed Sékou Touré in Guinea, produced agitprop at the behest of Kwame Nkrumah, crisscrossed Congo with Antoine Gizenga proselytizing for unity, built a base for a cadre of Angolan freedom fighters, organized an African women’s movement, and rose to international prominence as Patrice Lumumba’s chief of protocol in Congo. After Lumumba’s assassination in 1961, Blouin found refuge in freshly independent Algeria, then a hub for anti-colonial revolutionaries, many of whom passed through Blouin’s apartment. Liberation was, for Blouin, a pragmatic and social affair, not yet dominated by the speculative or apocalyptic tone the word carries now. But, to borrow her friend Nkrumah’s phrase, “the end of empire was accompanied by a flourishing of other means of subjugation,” and political militancy sank in the mire of economic brutalities—structural adjustment, international usury, comprador governance. The clock of the world ticked away from Blouin, too. She died disappointed and forgotten, in Paris, in 1986.

This reissue of her 1983 memoir, My Country, Africa, is part of Verso’s Southern Questions series, edited by Adom Getachew and Thomas Meaney. The book was one of the source materials for Johan Grimonprez’s 2024 movie Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat, and a South African literary prize was recently named after Blouin. It is unquestionably timely, its punctuality linked to renewed international focus on the genocidal pillage of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the revitalization of the anti-colonial paradigm by the Palestinian resistance. As the ruling class continues to intensify the “capitalist triage of humanity” (Mike Davis) condemning the Global South to permanent devastation, the ambitions of Blouin’s political milieu—Pan-Africanism, Bandung, universal humanism, moral triumph—seem to offer a ghostly off-ramp, a turn not taken but perhaps still out there somewhere in the irrealis. Lumumba’s assassination dealt a terrible blow to the struggle for African liberation. But his martyrdom has also preserved his political promise, the sense that things could have been otherwise, that another world’s arrival once seemed imminent. Then as now, resistance is maligned and obscured by those whose power it seeks to overturn, but here is Blouin, speaking across decades with absolute clarity: “Everything is a matter of perspective, and above all what is important is the right to defend oneself. That is the basis of all other rights.”

“I know that you can die twice,” writes Blouin’s daughter Eve in an epilogue to this new edition of the book that corrects the previous edition’s “undue emphasis on racial identity” and anti-Soviet bias. (Translator Jean MacKellar, who edited the first edition, was a friend of Andrée Blouin’s and the author of a handful of unprepossessing books, including a feminist disquisition on rape that breezily asserts that 90 percent of rapes are committed by black men, and a romantic novel set in Hawaii.) “My mother’s death was greeted with dreary indifference. . . . To be forgotten is a second death.” Andrée Blouin could not have known how many times she would die, but she tells us that she was born twice, like a convert, first physically and then politically. The first time was in 1921, in the French colony of Oubangi-Chari (now the Central African Republic), to a fourteen-year-old African mother and a forty-year-old French father. She was born again in 1958, a “mysterious conversion” prompted by a photograph of Ahmed Sékou Touré in a small store in Siguiri, Guinea: “A spirit, a light, a recognition—I hardly know what to call it—came over me. . . . I felt sure I heard words spoken. ‘Why are you on the other side, in this struggle? Why are you against us?’”

The two sides are the African independence movement and European colonial power. Between them there is no compromise, no intermediate position. If the existence of children born from mixed relationships, like Blouin, seems to promise not just a biological but also a political synthesis, this is more often revealed as an illusory, penumbral effect of the colony. For Blouin, the mixed-race population of the orphanage in which she is incarcerated as a three-year-old is irrefutable evidence that something other than economic convenience and civilizing largesse attracts Europeans to Africans, “proof that the racism on which colonialism was built had failed,” but this racism is all the more vicious for its supposed failure in the realm of sexual desire. “It was while I was still in the orphanage-prison that I first identified with the struggle for freedom of my black countrymen. Like them I was beaten with the chicotte, a whip made of ox sinews. Like them I was the victim of injustices of which I hardly knew the name but against which my blood never ceased to rebel.”

Although Blouin devotes a substantial part of her book to her childhood, her first birth is a chance event that the colony can only give the scant meaning of a scandal or a sin. The shared material experience of oppression—a solidarity of fact—is the noncontingent premise of her second birth. Another piece of happenstance, her second husband’s technical job at a mining company in Guinea, means that her awakening into political consciousness comes in the midst of the popular campaign that secured Guinea’s historic vote for independence and gave Touré the presidency. Blouin throws herself into the work leading up to the September 1958 referendum, even leaving her sick baby at home to go deliver a speech at a campaign event. “This, for me, was a real sacrifice. It measured my feelings for a free Africa, even more than the dangers to our persons that we courted.”

The sacrifice is especially significant because Blouin traces her politicization to an event less mystical and far sadder than her transformation by Touré’s portrait, the death of her two-year-old son René from malaria. “Only Europeans had the privilege of obtaining shots of concentrated quinine. . . . The African children who were stricken with malaria often died because they could not have the medicine.” Blouin’s eerily spare narration of René’s death culminates in a rejection of fate: “I refused to allow, refused to understand, refused to accept the death of my son.” Politics stands on the side of this refusal. Her campaign in the aftermath of her son’s death to change the quinine law is her first explicitly political work, though it follows the pattern of her early struggles against authority in the orphanage, a microcosm of the colony where “the nuns . . . knew I was dangerous.” At eight years old, she witnesses a “forbidden spectacle,” a forced march of political prisoners past the orphanage. “In spite of the fact that they were being whipped, the prisoners continued to shout their demands. . . . I had never seen such courage before. It stirred me with a passion to be equally strong.” These moments of witness give a basis for her later commitments, but they cannot in themselves transform her destiny from “strange detritus” of the colony to active agent of her own life. For that, she needed the portrait of a leader, as the concentrated expression of a collectivity, a political movement.

“Fate gave me fourteen years in an orphanage for girls of mixed parentage, from which all my subsequent experiences seemed to derive,” writes Blouin of her turn to politics. “My fate was swerving in a new direction now.” Yet the first fate retains its hold over her, an uninterpretable origin like the navel of a dream. At nineteen years old, Blouin travels by boat down the Congo River. The trip, an escape from a drab life as a seamstress in a Brazzaville slum, nevertheless expresses her privilege as a métisse: she is allowed to occupy a whites-only cabin because she is a friend of the captain, and falls in love for the first time with a handsome Belgian aristocrat working in systematized colonial plunder. Yet she is “marked” by another penetrating moment of injustice. The black passengers travel in the boat’s open hull with “no protection against either sun or rain” and are forced to carry heavy loads of wood to fuel the boat. When one of them is bitten by a snake, the teenage Blouin is “almost ashamed of my cabin, of my privileged existence, while my black brothers were outside, exposed to the dangers of the jungle. . . . I was shocked by this event.” Did the words she wrote as Lumumba’s speechwriter bear the trace of her experiences, as illuminated by this book? She quotes the speech he delivered to mark the independence proclamation of June 30, 1960, without revealing that—according to her daughter’s epilogue—she wrote it herself. Among the injustices he enumerates, “Who will ever forget . . . that blacks travelled in the holds of the barges, beneath the feet of the whites in their luxury cabins.”

Blouin witnessed Lumumba’s extraordinary life at first hand, as comrade and confidante, advising on strategy and hosting visiting diplomats in her role as chief of protocol. She sketches with quick, definite strokes his unswerving optimism bordering on the innocence of a holy idiot: “Poor Patrice! It is true that those who are of the best faith are often the most cruelly deceived.” His talent for hope was inextricable from his capacity to channel inchoate popular desire for freedom into a movement, but it was also his undoing. “His goodness will ruin us,” says his deputy Antoine Gizenga—admittedly not a problem that any Congolese leader has had since then. Blouin’s portrait of Lumumba is, as Getachew and Meaney’s introduction puts it, “full of imaginative sympathy but also a cool-headed assessment of his room for political maneuver.” Hers is also the judgment of a whole milieu, bearing a strong resemblance to Frantz Fanon’s anonymously published article on Lumumba in the revolutionary Algerian newspaper El Moudjahid, which Blouin later also wrote for. “He had an exaggerated confidence in the people,” writes Fanon. “The people, for him, not only could not deceive themselves but could not be deceived.” Fanon and Blouin spent time together in Ghana in 1960, the year before both Fanon and Lumumba died, one of cancer and one of capital.

To invoke Fanon here is only to emphasize that Blouin’s book is a memoir, not a manifesto. Her political writing—the ghostwritten speeches, “the first leaflets for a free Angola,” “broadcasts called The African Moral Rearmament to teach the Congolese people the need for unity”—is so far uncollected. In this book, beyond her deep feeling for the injustices of colonization, Blouin confines her political beliefs to desultory commentary. Understanding her intellectual relationship to the wider anti-colonial movement requires some reading between the lines. In the final chapter, she provocatively suggests that Africa’s “susceptibility to cynicism and corruption comes from the fact that African independence was not won in the crucible of war.” Though the thought is all her own, there is a resonance with Fanon’s emphasis in The Wretched of the Earth on “the important part played by the [Algerian] war in leading [the Algerian people] toward consciousness of themselves,” and his warning in the pages of El Moudjahid that “the greater danger that threatens Africa is the absence of ideology.” He died before the IMF stranglehold began to close around Africa’s throat, while Blouin lived to see her movement’s ruin.

Blouin’s political commitments are also, in a way, absent of ideology; at heart, they are personal and emotional. She conflates her love of Africa with her love of her mother Josephine, whose life—dubiously partnered to a wealthy white man, possessed by trivial petty bourgeois aspirations, eventually paralyzed by Mobutu’s soldiers—serves as a kind of political allegory. Although Josephine “detested all my efforts to improve the lot of my people,” for Blouin her work “is inseparable from my feelings for Josephine, and for Africa. My little mother with her marvellous smile, and the heart of a child. My marvellous Africa, where the sun warms all and laughter is king.” This doesn’t beat the charge of exoticism, but it is deeply heartfelt, with the fierce loyalty of a child longing for her absent mother. In Congo, Blouin founded a women’s movement that aimed to liberate village women like her mother, its aims a mix of radical political education and patrician moral improvement. “Most of [the women], by the time they were twelve, had already had relations with a man. I am ashamed to speak of such things,” she winces. Her mother was thirteen when she married her father.

The “contradictions” of Blouin’s parentage are unresolvable, but her love for her mother compels her to see her story in the best possible light. “How did it happen that this forty-year-old man from an exceptionally bourgeois and traditional background should find himself captivated by a thirteen-year-old girl of a remote and primitive village?” Anyone not conceived as a result of this relationship would not feel as much compelled to drape its sharp edges in tulle. Her attempts at a balanced description of their love have a sweetness approaching nausea (perhaps MacKellar’s influence) and read more painfully than open criticism. “Josephine was a child when he found her, a child designed to love and please. Her heart-shaped face radiated the beauty of Africa . . . one must concede the usefulness of this relationship for him . . . he did not feel alone because he had this delicious girl for company.” But morality has notoriously little purchase on experience, and Blouin is telling the truth when she emphasizes that this pedophiliac liaison “developed into an affection that . . . was to last my father’s lifetime,” and provided the meaning of her mother’s life.

However hard she tries to honor her mother’s love for her father, Blouin knows that her parents’ relationship expresses, rather than contravenes, the European pillage of Africa. In a conversation shortly before her father’s death, she finally expresses her anger toward him, the hatred—“more than a little”—that has motivated her efforts to love him. And yet she sees in his patriotism to France a reflection of her commitment to African liberation. In the moment of historical inversion as “Nazism transformed the whole of Europe into a veritable colony” (Fanon), her colonial father’s patriotic anti-fascism was “an exalted repudiation of all that his life had been until then.” His significance to her is as opaque as her mother’s is radiant. Like her mother, she marries white colonials. Unlike her mother, she does not experience it as a victory. “All my life I had been trapped by racism. Why should my heart now turn toward that which had so often made me suffer?” The mixed girls in Blouin’s childhood orphanage are “brown-skinned, well-oiled robots, docile, disciplined, totally submissive.” Like a colonial version of Godard’s Alphaville, Blouin at times seems to narrate her life as the story of how one robot overcomes her programming through love. “Only when I had been married—ironically, twice to white men—did I find the equilibrium and courage to become active in the cause of my people.” The paradox belongs to the first birth and can’t be unpacked. “Perhaps I will never be fully able to integrate the meaning of [my father] in my life.”

What can’t be integrated remains visible. For all of childhood’s powerlessness, its mystery, the implacability of its injuries is the pattern of resistance. “You cannot tell a child to forget all it has suffered in an unhappy childhood by saying, ‘You are big now, that is past. Let us be friends.’ One does not forget. We who have been colonized can never forget.”

Hannah Black is the author of two small books, Dark Pool Party (Dominica/Arcadia Missa, 2016) and Tuesday or September or the End (Capricious, 2022). As an artist, she is represented by Arcadia Missa in London and Isabella Bortolozzi in Berlin. She currently lives in France.