The artist Paul Thek sits with his face half cast in shadow, a look of curious expectation in his eyes. It is one of Peter Hujar’s relatively rare upright portraits: in many of the photographs in Portraits in Life and Death, his 1976 book recently reissued by Liveright, the subjects are reclining, sometimes tucked in or seemingly asleep. Hujar’s models are a who’s who of artists and intellectuals from New York’s early-1970s avant-garde, from William S. Burroughs to John Ashbery to Divine. Some seem melancholic and distracted, their eyes half closed or straying from Hujar’s lens. Others are alert, almost breathingly present, holding the viewer’s eye. What is most striking about all of them is their lack of artifice or self-consciousness, a quality of frank guilelessness that disarms. No one has their disguises on: several famous queens—Charles Ludlam, Larry Ree—appear out of drag. The poet Anne Waldman lies languid, with the broad sleeves of her robe puddling at her elbows atop a checkered quilt. The writer and curator Vince Aletti, one of Hujar’s closest friends, sits half turned toward the camera, his arms folded with one hand clutching his upper arm, skinny in that particular ’70s way, and gazes at us with the big, sorrowful eyes of a bloodhound. Meanwhile, Fran Lebowitz, chubby cheeked with youth, perches on the edge of a table, leaning forward with a wry stare, not yet fully in possession of what would become her signature deadpan.

Hujar, who died of aids in 1987, eleven years after Portraits was published, photographed exclusively in black and white, and he achieved an almost uncanny intimacy with his subjects. The way their eyes meet the camera with frankness and affection, placing the viewer in the photographer’s place, almost makes you want to apologize and leave, like you’ve walked in on something you weren’t meant to see. Along with their sadness, several of the subjects wear gazes of calm sensuality that remind you what Hujar looked like: he had the face of a king, strong in the cheekbones and chin, and so when his subjects were being photographed, they were in the presence of a man they must have found strikingly beautiful. All affectations are dropped—reclining in a ribbed turtleneck, even Susan Sontag looks relaxed. With the inevitable exception of John Waters, nobody smiles.

Among the subjects, Thek—Hujar’s frequent collaborator and sometimes boyfriend—is uniquely engaged. His gaze meets the viewer’s. What is most noticeable is Thek’s mouth—hinged open, ringed by stubble. When I first saw this portrait, I didn’t know why I couldn’t look away. It took me some time to see that Hujar had captured Thek speaking, that his mouth was breathing out a word. Gazing at him in the slanted light of Hujar’s studio, I wanted to hear what he had to say.

Portraits in Life and Death was the only book that Hujar published in his lifetime, and it was not a great commercial success. At the height of his career, he was often compared to Robert Mapplethorpe, and not favorably. It’s easy to see why Hujar reminded viewers of Mapplethorpe: the men knew each other, and they had some of the same style and subjects in their work—arresting black-and-white images of the gay downtown demimonde. But Hujar had a radically different emotional posture. While Mapplethorpe’s photos are almost giddily provocative—campy, winking, triumphantly obscene—Hujar’s have a disquieting and mournful quality. This is part of why Hujar’s work was considered difficult at the time, even among people who admired him. In his deft introduction, Benjamin Moser quotes Mapplethorpe discussing Hujar’s photos. “Everybody understands he’s a great photographer,” Mapplethorpe said. “But when I put something on the wall, I don’t want to look at it and cringe.” Mapplethorpe saw their shared New York art world as ushering in a new age and looked eagerly toward the strangeness and revolt of an optimistic future. But Hujar looked at that same world and saw it as fragile, temporary, endangered. In the book’s final quarter, when the portraits shift from intimate images of his living friends in New York to shots of mummified corpses in the Palermo catacombs, the progression is not as jarring as you might expect. Maybe Hujar thought of himself as creating before-and-after shots of the inevitable: his loving attention is constant, whether his subjects are dead or alive.

Coming after the repressive ’50s, and after the defeat of the ’60s New Left, the audience who received the book in 1976 probably thought of themselves as survivors. Still, Hujar grieved for them, as if they were already part of the past. Portraits in Life and Death has since become iconic, achieving a status in the years since Hujar’s death that would have staggered him while he was alive. Perhaps it is because the New York that Hujar knew has been so thoroughly destroyed—by time, by aids, by gentrification—that his tone of wistful lament now mirrors our own. He lived in the East Village among writers, artists, and intellectuals, all living and working in close proximity, in an era when cheap rent meant that artists could get by on very little money, leaving them more time to work. It was a time before the artistic and intellectual worlds totally took on their now-permanent posture of frank careerism, and before they had to. People could spend time making things that excited and challenged them and still manage to live in New York.

Hujar, too, has become metabolized in the twenty-first-century imagination as an icon of a mythic time, an impression that is perhaps more starkly made by the tenderness of his portraits. The East Village arts scene of the ’70s generated the kind of formative work that younger generations built identities and worldviews around; the subsequent aids crisis meant that many of the artists who made that work died young—among the subjects in Portraits, both Thek and Charles Ludlam died of aids. Some of Hujar’s other famous subjects, like the artist David Wojnarowicz and the Warhol Superstar Candy Darling, would die at thirty-seven and twenty-nine, respectively. Their untimely ends have the effect of preserving these figures for us as they were—brilliant, tragic, and gone before they ever got a chance to disappoint us. For all the peculiar specificity of his vision, any encounter with Hujar’s work now bears the weight of this history: several decades on, we see not only the virtuosity and potential of Hujar’s world, but also the tragedy that was coming. “Photography also converts the whole world into a cemetery,” wrote Susan Sontag in her introduction to Portraits’ first edition, written from her hospital bed just hours before the first of her surgeries for cancer. “Photographers, connoisseurs of beauty, are also—wittingly or unwittingly—the recording angels of death.” When Portraits was published, the first reported aids case was still five years away, and Donald Trump was just a sleazy, nightclubbing landlord. Would Hujar’s subjects have looked different if they’d understood themselves to be teetering on the edge of a catastrophe? The faces in his portraits bear a range of emotions—they look inquisitive, or mischievous, or very tired. To me, looking at them from across a long historical distance, they also look a little naive.

Perhaps it’s fitting, then, if cruel, that Hujar’s artistic reputation only took off after his death. His great gift, after all, was his prescience. You don’t know what you have until it’s gone.

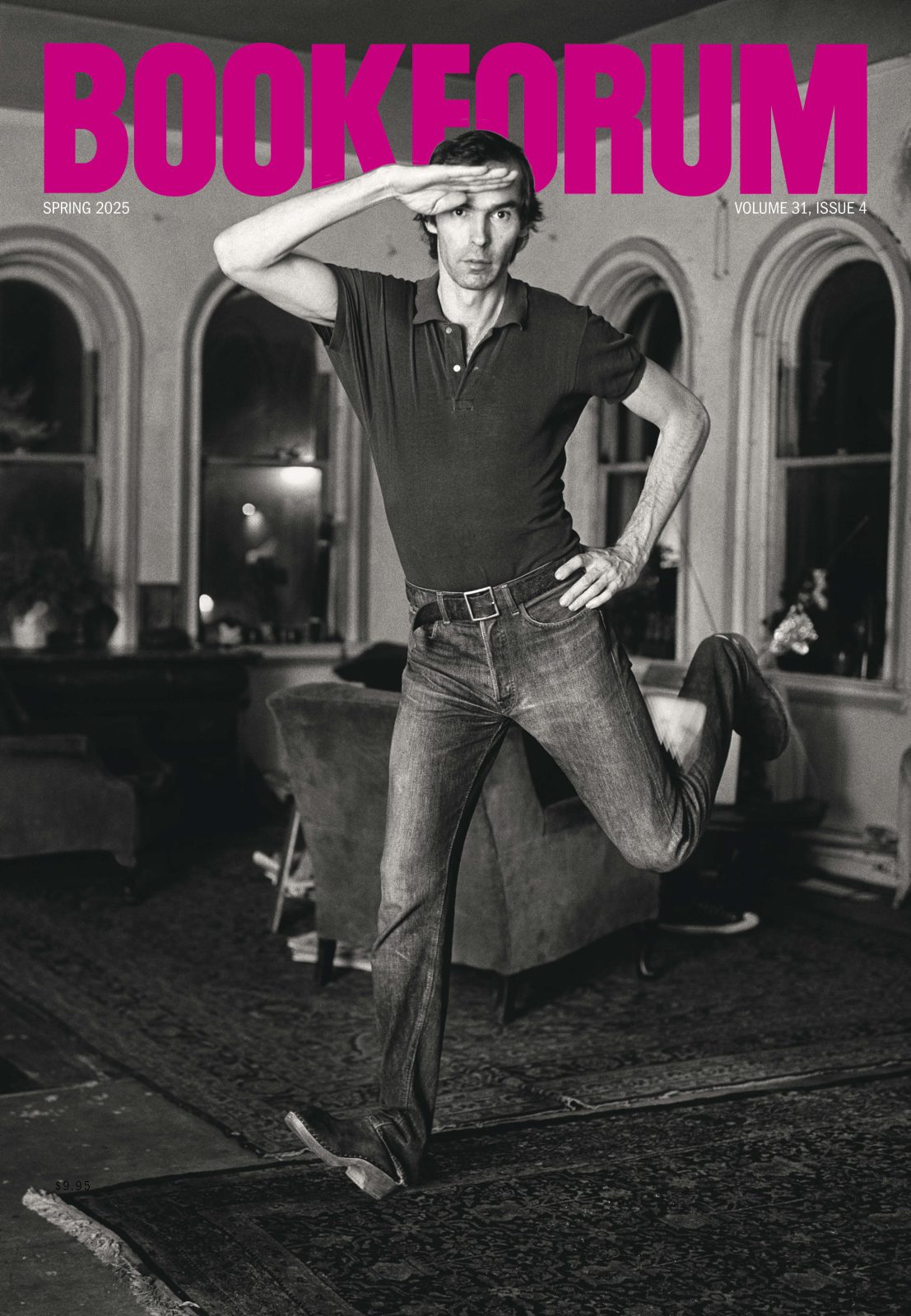

For all the romanticism that’s now projected onto it, Hujar’s New York could be a dangerous and unlovely place. In a Hujar self-portrait that accompanies Moser’s foreword, the photographer leaps in the air in what appears to be the living room of his loft, a few overstuffed chairs and a rug in the background behind his thin frame. Hujar’s posture is playful: he has one foot kicked aloft, one hand rigid across his forehead in a mock military salute. Behind him, the apartment is an undeniable shithole. “The floor is scuffed, the radiator covered in thick grime,” Moser writes. “Someone seems to have started, with impatient streaks, to paint one of the walls.”

Playing amid the ruins with irreverence, empathy, and defiance—rather than despair—as the posture of the oppressed: this is what feels so urgent and instructive about Hujar’s example. The joy and creativity produced by gay underground artists of that pre-aids era was meaningful because it was wrested from conditions of deprivation and pain.

That pain could be acute. The lives of Hujar and his friends contained not only impish defiance but also addiction, deprivation, ostracism, and physical violence. Hujar, in particular, wrestled with his own private demons. After a wounding childhood—in which he was alternately abandoned, neglected, and abused—Hujar left home as a teenager and made his way to the School of Industrial Arts (now the High School of Art and Design), where a teacher recognized his talent and encouraged him to intern at commercial photography studios. Hujar never much liked being a fashion photographer: the form celebrated surfaces, and did not allow for his style of disarmed honesty. Unlike some of his friends—who disdained and rejected the professional art world—Hujar thought of his own artistic marginality as a failure, one that pained him. He wanted to publish another book after Portraits but was never able to. As with many people’s professional disappointments, this may have been partially Hujar’s own doing. “His prickliness alienated many who may have nudged along his career,” Moser writes. Friends remember his angry moods, which could turn violent: he once broke a chair in an argument. Self-doubt didn’t help. Hujar never quite seemed to believe in his own worth, or in other people’s esteem. “He never believed that people actually valued his work,” writes Cynthia Carr in Fire in the Belly, her biography of Hujar’s onetime boyfriend, close friend, and protégé David Wojnarowicz, whom Hujar met in 1981. “Even when they told him they did.” They valued Hujar as a person, too. For the most part, his charm outshone his brusqueness. “Hujar was so handsome, charismatic, seductive, and engaging,” Carr writes, that when friends like Aletti introduced people to him, they’d frequently get a call the next day declaring a crush on Hujar.

Self-reproach—or merely a sense of being an outcast—can cultivate insight into other people. It’s easy to see through to their hidden shames and denials when you have such an intimate acquaintance with your own. Whatever his faults, Hujar brought the perceptive intelligence that marks his portraits to his life away from the camera. In one-on-one interactions, he was almost preternaturally nonjudgmental. “The beauty of things broken and damaged was what he was interested in,” said the writer Stephen Koch, a longtime friend, who is now the director of the Peter Hujar Archive. Wojnarowicz described an exchange early in his friendship with Hujar, when their relationship was still sexual, when Wojnarowicz disclosed his own history of sex work, a part of his life that he was ashamed of. “We were having dinner, and I fully expected him to reject me,” Wojnarowicz said. “And I remember he just said, ‘So?’” Wojnarowicz describes Hujar’s witness and acceptance as a singular moment of loving absolution. Wojnarowicz’s relationship with Hujar permanently changed all aspects of Wojnarowicz’s art and life. “Everything I made,” he would say of his subsequent art career, “I made for Peter.”

What would it mean to be seen the way that Hujar saw his subjects, the way he saw Wojnarowicz—with total comprehension, devoid of all delusions? For Wojnarowicz, Hujar’s love was beyond familial, or even spiritual: it was the sort of life-altering understanding that people in our own age often seem to be seeking, unsuccessfully, in religion or intensive psychotherapy—a chance to be understood with perfect clarity.

I admit that I do not always rise to the level of generosity that Hujar models in his photos. When I look back on the twentieth century—and on the intellectuals who shaped it, both in and out of Hujar’s studio—I not only feel envy at the cheap rents and sense of artistic freedom, but also a bit of anger. These are people who lived in more prosperous and in some ways stabler times, who were abandoned by extractive capital and a homophobic government, but who managed to build a sanctuary for themselves along the way. They made something beautiful for themselves. But they did not manage to make it last, let alone pass it on to us. There is also, I know, the element of resentment—wounded and childlike—that underlines so much grief. Of Hujar’s twenty-nine living subjects in Portraits in Life and Death, only seven are known to still be alive at the time of this writing. Looking at the people we have lost, young and beautiful and breathing, I want to scream through the pages that they need to keep themselves alive, and to stay with us. But this demand is as unwise as it is impossible, and it is contrary, too, to Hujar’s vision. To wish for them to have been more responsible, or more permanent, is to wish away the thing that makes him love them.

One way to read Portraits in 2025 is as an instruction in how to love people through and against history: to see them in the full breadth of their frailty, striving, myopia, and vanity—to see all the ways they tried to build a better world, and failed—and to extend them grace. Perhaps one day, someone will look back on us and at our moment and wonder how we could have looked so restful and young; how we could not have known what was coming. I hope that that person, if she ever exists, will extend to us what Hujar lent to his subjects: something like forgiveness.

The last eleven photos in Portraits in Life and Death are of mummified corpses. Hujar took the pictures around 1963, when he was on a Fulbright in Italy. Like his portraits of living subjects, Hujar tends to isolate single corpses at the center of his frame, paying prolonged attention to the person that was. The bodies peek through glass-sided coffins or are propped up in wooden-framed crevices in the wall. The faces are sunken, dried out, sometimes reduced to skeletons. But the clothes remain impeccable. Five upright monks wear Franciscan habits; a small girl’s shriveled hands stick out from the embroidered cuffs of bell sleeves; the tiny, bulbous skull of a baby wears a ruffled sleeping cap. There is a tenderness in all these details. If Sontag thought that Hujar’s portraits exemplified photography’s formal mimicry of death, these are pictures of death that evoke their subjects’ lives.

When Hujar died, it was thought that the HIV virus triggered aids and killed a person within two or three years of infection. Later, researchers learned that untreated HIV can remain in the body without the patient’s developing aids for almost a decade. That means that in that jaunty self-portrait of himself at home, leaping in the air and saluting the camera, Hujar may already have been infected. Wojnarowicz was with Hujar when he died, and wrote that when Hujar took his last breath, Wojnarowicz’s impulse was to grab his Super 8 camera, to record “his open eye, his open mouth, that beautiful hand with the hint of gauze at the wrist that held the IV needle, the color of his hand like marble, the full sense of the flesh of it.” Among the resulting images, one is of Hujar’s face: covered in a rough, graying beard, sunken in at the eyes and cheeks from the wasting of disease, a flimsy hospital gown lining his clavicle. It bears a striking resemblance to one of Hujar’s images from the catacombs: a middle-aged man, skin dried and taut in death, with his face still fuzzed by a mustache, wearing a square cap. Like Hujar’s photograph, Wojnarowicz’s image is devastating in its gentleness. And like Hujar’s, it does not obscure the finality.

Moira Donegan is a columnist at The Guardian and a writer-in-residence at Stanford’s Michelle R. Clayman Institute for Gender Research.