Charlie Markbreiter

For low-vision viewers, bright colors, which reflect light, are easiest to see. The cover of Beatrice Adler-Bolton and Artie Vierkant’s new book Health Communism is thus bright blue––what Adler-Bolton calls “true blue,” and what the Pantone color guide calls #2736 C. The coauthors’ names aren’t on the cover. Instead, they’re listed inside, on one of the opening pages. Adler-Bolton and Vierkant are perhaps best known as two of the hosts of Death Panel, a health justice podcast which takes its name from Sarah Palin’s 2009 claim that federal universal health-care would lead to state-sanctioned austerity and murder (which, as

This is a great book by a great person, so let’s get logistics out of the way: Lou Sullivan was America’s first “officially” gay trans man; he started keeping a journal at age eleven, with the hope that eventually these diaries would be published. This didn’t happen while he was alive. Lou died of AIDS in 1991 at thirty-nine years old. You don’t need me to tell you that, for many transes, this was and is a tragedy, whatever that word can mean for us now. Lou’s diaries are available, finally, for public intellectualizing and interpersonal adoration. Edited by Ellis

“Eve Sedgwick, Once More,” a eulogy penned by theorist Lauren Berlant about their former mentor, began as follows: “Once upon a time, a very round, very red-headed woman . . . concluded a talk on the erotics of poetic form by inviting my colleagues to rethink sexuality through considering, among other things, their own anal eroticism.” Sedgwick wasn’t trying to be a shock jock. The late literary critic was the cofounder, arguably, not just of “queer theory,” but of what we now call “post-critique.” She is perhaps best known for coining the phrase “reparative reading,” a framework she came to

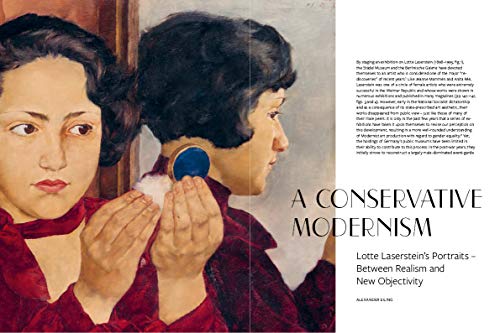

In Self-Portrait with a Cat (1928), Lotte Laserstein’s hair is short, pushed off her face. The cat holds its pose because it’s tranquilized with brandy. Laserstein’s muse, and maybe lover, Traute Rose, also had short hair and liked loose clothing. In Tennis Player (1929), Rose watches a match while sportily grasping her own racket, waiting to play. For In My Studio (1928), however, she is La Grande Odalisque or she is postcoital. Laserstein, wearing a white linen smock, pays attention to what she is painting; the painting pays attention to Rose’s body. Laserstein’s and Rose’s androgyny was not an attempt