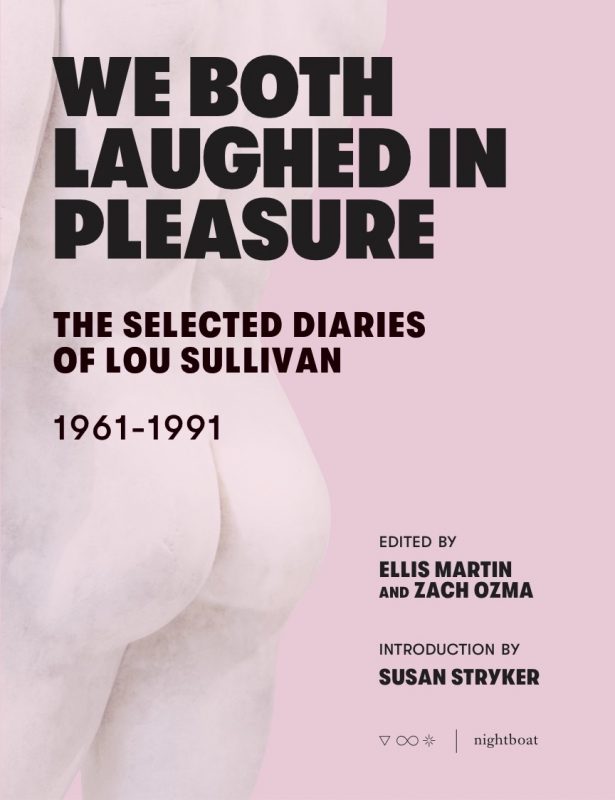

This is a great book by a great person, so let’s get logistics out of the way: Lou Sullivan was America’s first “officially” gay trans man; he started keeping a journal at age eleven, with the hope that eventually these diaries would be published. This didn’t happen while he was alive. Lou died of AIDS in 1991 at thirty-nine years old. You don’t need me to tell you that, for many transes, this was and is a tragedy, whatever that word can mean for us now. Lou’s diaries are available, finally, for public intellectualizing and interpersonal adoration. Edited by Ellis Martin and Zach Ozma with an introduction by writer and theorist Susan Stryker, We Both Laughed in Pleasure has a perky butt on its pink cover––which, luckily, is indicative of the book’s overarching tone. The legitimately unresolved formal tensions of autobiography as a genre––that it meanders, navel-gazes––are perfect for a Trans Literature burdened by the pressure to produce respectable texts whose protagonists, diplomatic envoys from the Land of Trans, aren’t allowed to be complex freaks.

Here, Lou is presented in all of his complex freakhood—beginning with his Beatle-mania. Young Lou would have died for Paul McCartney, or for the chance to become him. The desire to protect your bro, fuck him, and possess his body is a very transsexual clump of wants, each variously passing as the other (ha ha). The Beatles are “so perfect,” wrote Lou back when he was the devout, horny tween Sheila, living in his parents’ Catholic Milwaukee home. “Model yourself on them + you’ll have no worries.” These early entries shimmer with gender euphoria: “To lessons I wore a white shirt, tie, and black slacks. I love it!” The short, definitive clauses are rounded off by an exclamation mark, a writerly flourish that he kept through adulthood. I love it!

It’s the early ’60s. Trans tumblr teens aren’t posting definitions of dysphoria online. Instead, there was just a feeling of constant, ambient wrongness––of floating above your own body even as you’re burrowed somewhere in it. “My problem,” wrote Lou, “is that I can’t accept life for what it is. . . . I feel there is something deep and wonderful underneath it that no one has found.” Older boys seemed to have it. Lou loved Bob Dylan and Lou Reed, whose first name he later took. If trans is fate, it’s also a matter of chance. Lou saw Lou Reed in an underground Milwaukee club that doesn’t exist anymore. He was in his early twenties and in his first long-term relationship, with someone named J, who sometimes let Lou “put all the jewelry on him” when they boned, “my long long black necklace, over his shoulders, his back, his chest.”

But being with J wasn’t always like that. Most of the time, it was bad. J was OK with Lou being masc as long as it was just drag. But he wouldn’t treat Lou as another man who wanted men. It can be hard––as the nuanced, empathetic, historically conscious readers we all are––not to yell at Lou to just LEAVE. BREAK UP WITH J AND BLOSSOM LIKE THE TRANS FLOWER YOU ARE. This is, of course, what Lou was trying to do. The problem wasn’t the ends but the means: gender-identifying with your male lover so tightly that losing him would have felt like losing a way to imagine yourself as a man. “I want to be him,” Lou writes. “If I can’t have him, I’ll become him so I can always be with him. Crazy thoughts. Crazy interpretations that made me cry + cry + phone + phone but no answer until I fell asleep.” In 2019, if I describe Lou as abject, am I scabbing? Maybe. Maybe not. There’s still no best way to discuss dysphoric self-hate in public. But dysphoric self-hate still exists.

Lou detransitions for three years––in part, to make J finally fall in love with him. He writes, “I continue to feel more like part of the human race, yet less like a person.” Lou and J break up. This cycle of self-destructive gender-desirous relationships repeats with another willowy dude, T, who juices Lou’s heart. And yet there also are, years later, pleasures that had once only been half-realized fantasies. “Can’t even believe how goddamn good I feel,” he wrote in his first entry post–top surgery.

Lou’s medical transition also loosely marks the start of his public trans politics. He was repeatedly denied access to surgery due to his homosexuality. Capitalist notions of gender operated on a scarcity model (and still do, in other ways), in which you’re allowed to be a trans man or a gay man, but you can’t––you greedy, weird child––have both. That gay trans men even developed as a concept, let alone were allowed to transition as such, is in no small part thanks to Lou’s work: He successfully campaigned for the removal of homosexuality as a contraindication for sex reassignment.

At this point, it becomes difficult to write of his accomplishments without sounding like a “Best Of” list: Lou volunteered as the first trans gay peer counselor at San Francisco’s Janus Information Facility; authored, in 1980, the first known FTM4FTM info book, Information for the Female-to-Male Crossdresser and Transsexual; wrote the first biography of Jack Bee Garland, who lived in San Francisco at the turn of the century as a passing trans man. Even after being diagnosed with AIDS, Lou continued to meet, befriend, and mentor trans men from across the world. This list of contacts would become FTM International. If a “community” (please find me a better term!) can’t be organized until its shared goals and experiences are articulated, Lou did literal community organizing.

If I am perhaps too glowing in my praise of Lou, that’s probably because I can’t physically imagine myself without him.

Charlie Markbreiter is a writer in New York.