Christian Lorentzen

THE PATERNITY OF Hicks McTaggart—defender of dames, dodger of bombs, twirler of spaghetti, the amiable behemoth hero of Thomas Pynchon’s Shadow Ticket who prowls the streets of Depression-era Milwaukee—is a question his author leaves open. His mother, Grace, and her sister, Peony, “grew up in the Driftless Area, a patch of Wisconsin never visited by […]

I DON’T REMEMBER WHEN I first heard the term “incel” but I do recall my reaction: I don’t want to know about these guys. You feel sympathy for lonely people, of course, but it would seem that their constitution as a class or identity category in the internet age, while perhaps inevitable, can only compound […]

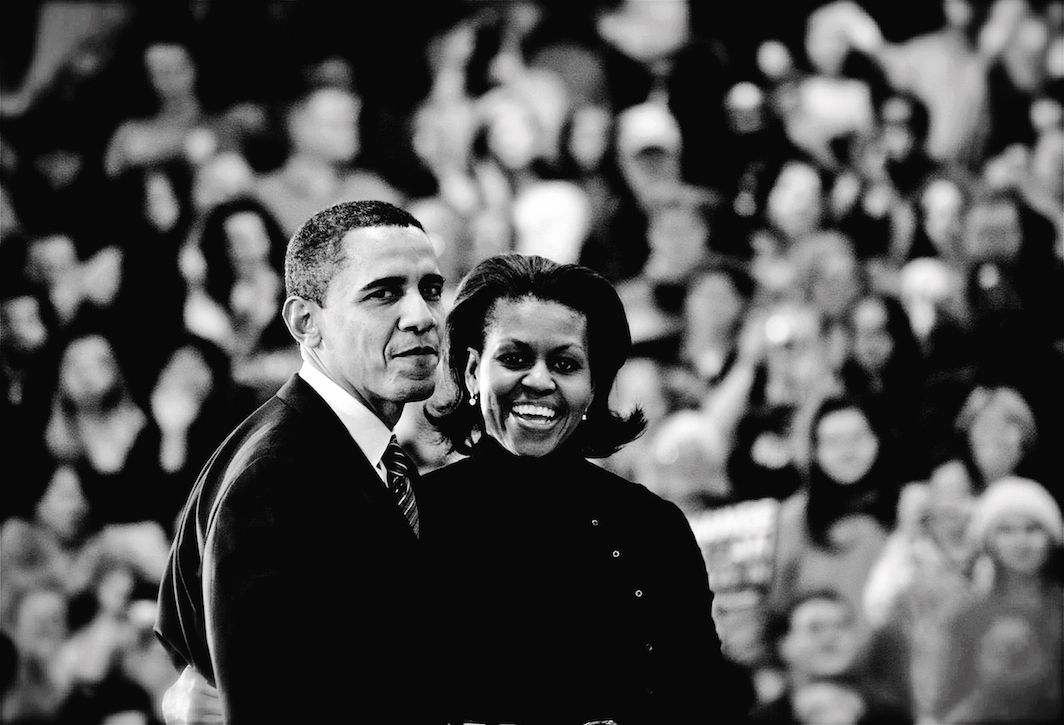

THE NOSTALGIA AMONG LIBERALS for the Obama presidency has lately crested such that it’s a surprise that proposals to overturn the 22nd Amendment haven’t gained traction, even in the fantasy realm of non-feasibility where a lot of American political thinking occurs. Given the centrist fetish for norms and process, a restoration of Barack Obama would be beyond the pale. Let him podcast, produce content for Netflix, and issue biannual lists of his middlebrow fiction faves. Still, there are believers in the restoration of another Obama, both on the paranoid fringe and in the dismayed middle. Lately my primary source of

THE DREAM OF AN ARTWORK that encompasses the whole world; of a novel that tells everybody’s story; of characters who feel and act and speak for us all; of the image that nobody doesn’t recognize. Yet it is the world and characters and images and stories themselves that stand in the way of that dream. They are too real and too small, too specific and too discrete to be for all. A person personifying history is still a person, history warped by and warping a personality. A dramatic narrative consists of speeches, acts, events. A consciousness is marred by the

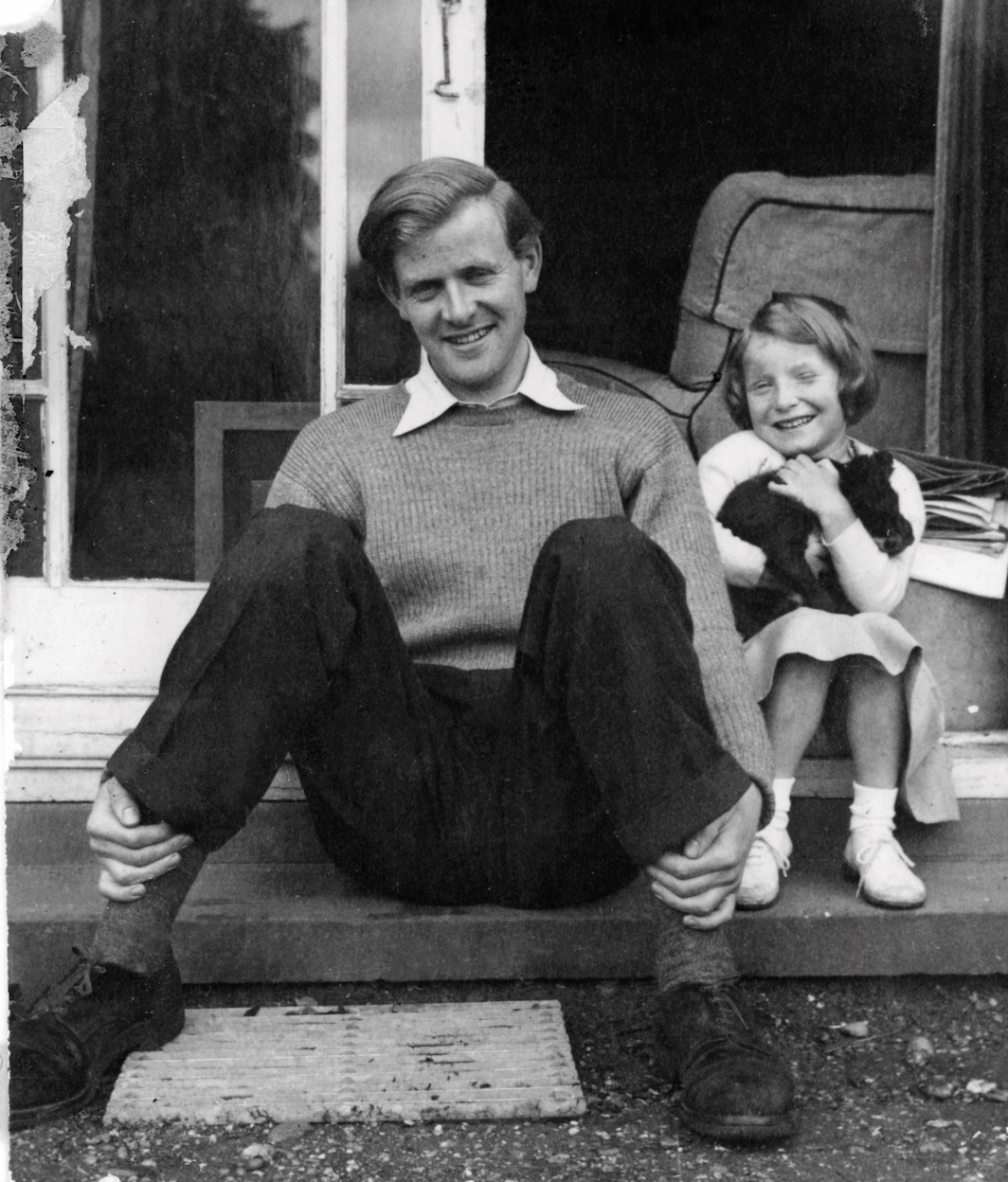

BORN DAVID CORNWELL in 1931, John le Carré was too young to go to war and thus too young to experience Britain’s patriotic struggle with Nazi Germany from inside the intelligence service, too young to have worked in alliance with the Soviet Union, and much too young to have been a university student in the 1930s, when many idealistic young Britons joined with the Communists because they were the staunchest opponents of fascism. He was sent to boarding school at the age of five, and it left him with a bitter feeling toward his country’s ruling institutions, even as he would

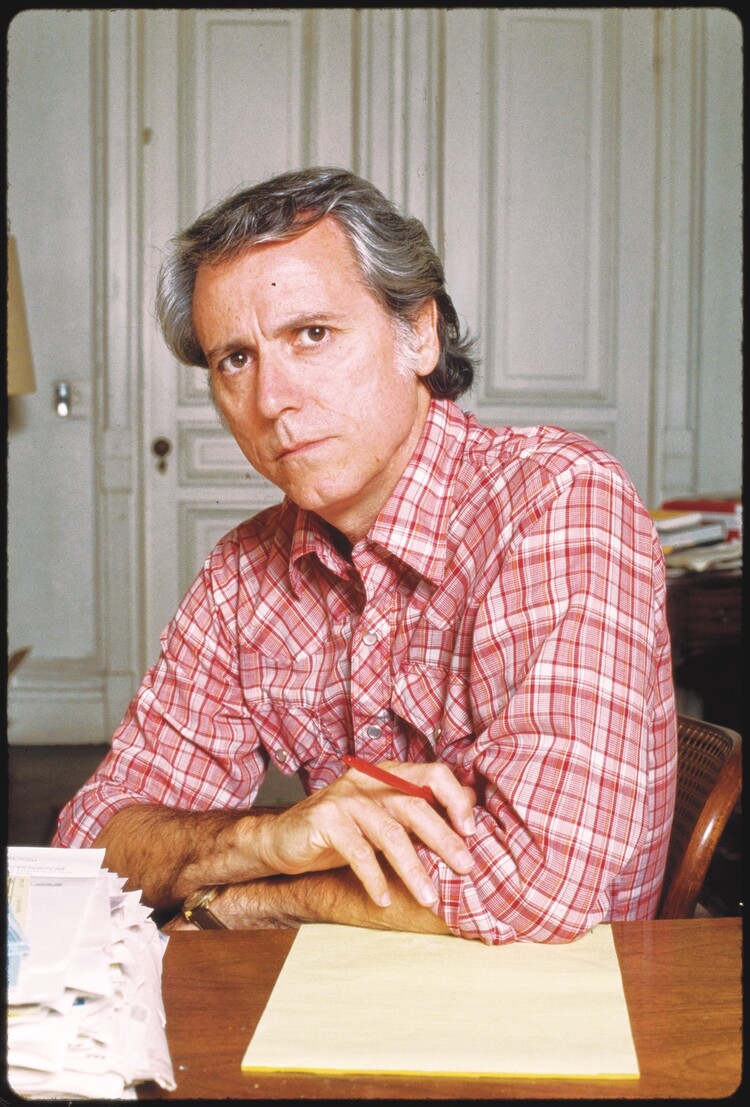

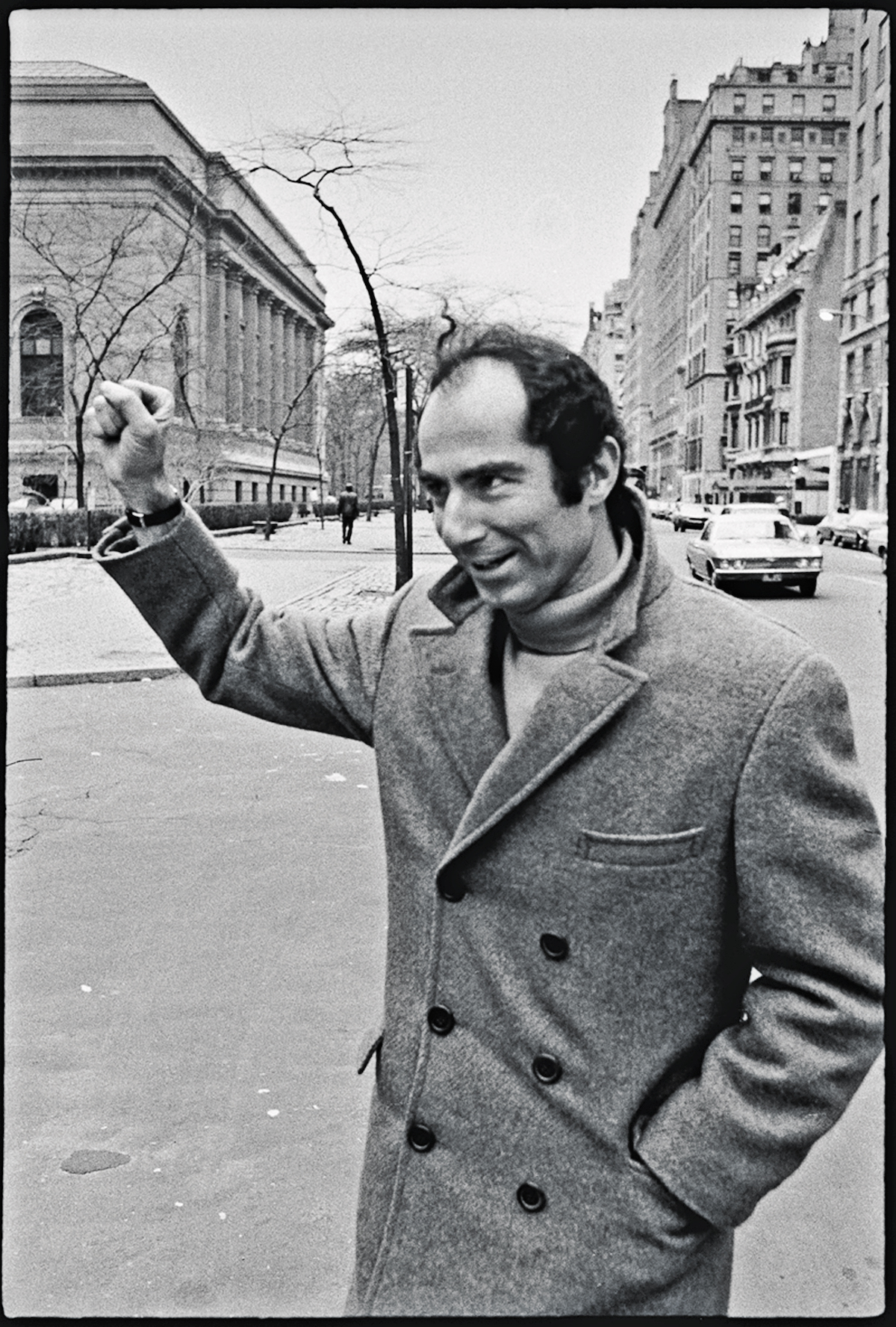

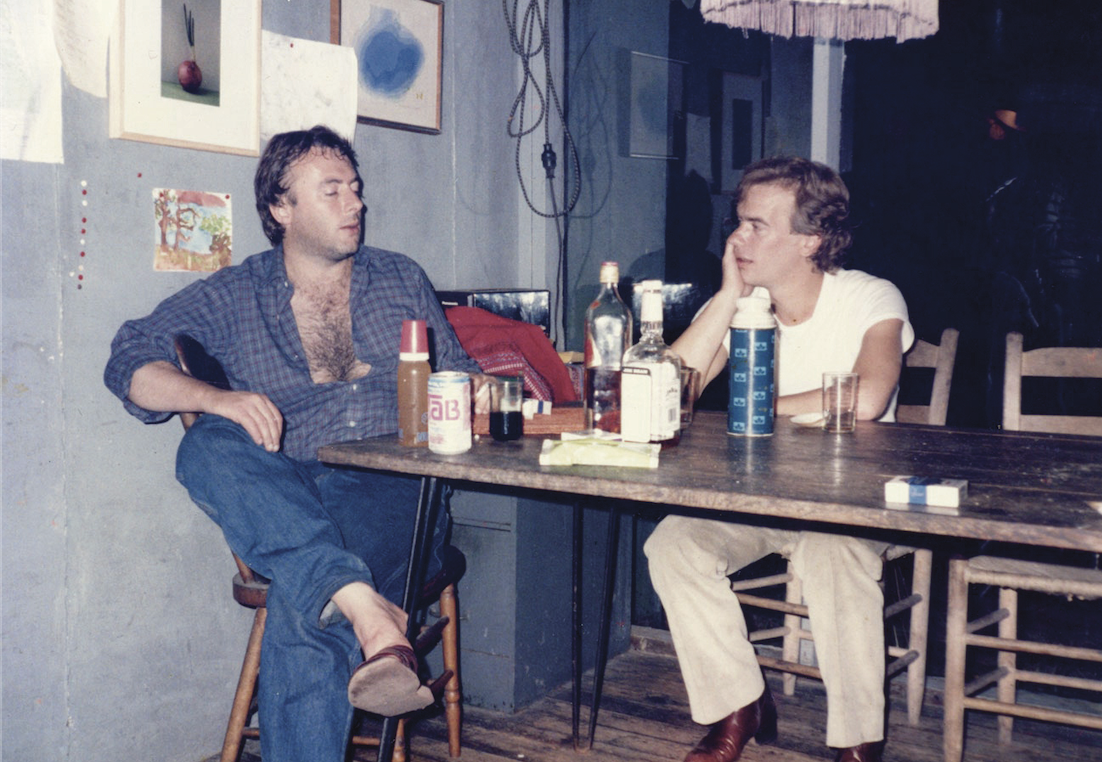

WHAT IS IT WE WANT from literary biographies? A portrait, surely, of the subject, something beyond the profiles and interviews that they grinned through whenever one of their books appeared. Perhaps even a good story. A prominent biographer once told me that there would never be a biography of Don DeLillo because all he ever did was sit at his desk and write his books: there’s no fun for a biographer in mining that kind of life. On the other hand, new books seem to appear every year on the short life of Sylvia Plath, the narrative thread always winding

PERCIVAL EVERETT’S NEW NOVEL begins in Money, Mississippi, the town Emmett Till was visiting from Chicago when he was lynched in 1955. The fourteen-year-old Till was tortured, mutilated, and shot in the head. His killers, Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam, tied his corpse to a cotton gin with barbed wire, and dropped it in the Tallahatchie River. They were tried and acquitted, and, though they admitted their crime to a journalist for Look magazine the next year, rules against double jeopardy ensured they were never brought to justice. The Trees opens at a family gathering of the descendants of

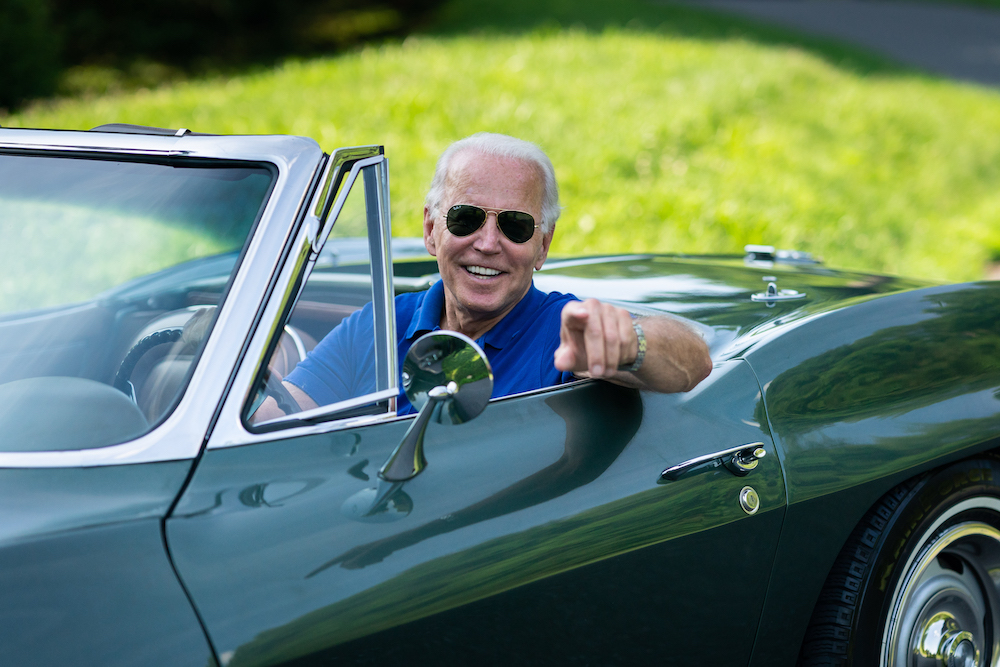

WHAT IS THE APPROPRIATE NARRATIVE MODE to capture the last few years of US history? What mode will fit the times going forward? Political eras lend salience to certain sorts of stories. We have just lived through a gothic phase of history, and a new sentimental age is upon us. These two modes of narrative have been alive, if not always dominant, in America since the eighteenth century, and they have lately defined our politics. The tropes of the Trump administration were those of a gothic nightmare—sexual perversion and predation, the sinister influence of forces emanating from the shadowy east,

MORE THAN REALISM OR ITS RIVALS, the dominant literary style in America is careerism. This is neither a judgment nor a slur. For decades it has simply been the case that novelists, story writers, even poets have had to devote themselves to managing their careers as much as to writing their books. Institutional jockeying, posturing in profiles and Q&As, roving in-person readership cultivation, social-media fan-mongering, coming off as a good literary citizen among one’s peers—some balance of these elements is now part of every young author’s life. It’s a matter of necessity and survival, above and beyond the usual dealings

“SENESCENCE” ISN’T QUITE THE RIGHT WORD for the stage the writers of the Baby Boom have reached. Sure, they may be collecting social security, the eldest of them in their mid-seventies, but the wonders of modern science may allow some another couple of decades of productivity. When the Reaper starts to come for the writer’s instrument, the first thing to go is flow, but that may not matter: fragments are in. In a decade or so, robbed of their transitions and reduced to accumulating prose shards, the octogenarian Boomers may find themselves newly trendy. A strange fate for a generation