PERCIVAL EVERETT’S NEW NOVEL begins in Money, Mississippi, the town Emmett Till was visiting from Chicago when he was lynched in 1955. The fourteen-year-old Till was tortured, mutilated, and shot in the head. His killers, Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam, tied his corpse to a cotton gin with barbed wire, and dropped it in the Tallahatchie River. They were tried and acquitted, and, though they admitted their crime to a journalist for Look magazine the next year, rules against double jeopardy ensured they were never brought to justice. The Trees opens at a family gathering of the descendants of Bryant and Milam. Present too is Bryant’s widow, Granny C (real name: Carolyn Bryant), who expresses regret that she falsely testified that Till had grabbed and propositioned her. “Well, it’s all done and past history now, Granny C,” her daughter-in-law tells her. “So you just relax. Ain’t nothing can change what happened. You cain’t bring the boy back.”

Soon enough “the boy” does come back, or seems to. Granny C’s nephew, Junior Junior Milam, and then her son, Wheat Bryant, are found dead, strangled with barbed wire. Found at each crime scene is the corpse of the same young Black male, unidentified and strangely not bleeding, and in his hands are the severed testicles of the dead white men. (In the novel both “Black” and “White” are capitalized.) The Black corpse keeps going missing from the Money coroner’s cadaver drawer, and it turns up again in the presence of a dead Granny C, whose body is unmutilated because she dies from fright, or (white) guilt, which in The Trees are one and the same.

The Trees is a wild book: a gory pulp revenge fantasy and a detective narrative that alternates between deadpan and slapstick modes of satire. It has all the right beats for the big screen, except that it’s too profane and obscene to be greenlit in Hollywood, even for the likes of Quentin Tarantino. His retribution epics offer an obvious point of comparison: The Trees is just as blood-soaked and just as hilarious as Inglourious Basterds or Django Unchained, but it comes with more authentic historical weight for being set in a dreamlike counterpresent rather than a cartoonishly counterfactual past. As a response to the Trump presidency—Trump is a character who speaks in its pages—Everett’s message is, put bluntly: Fuck you, you stupid, cowardly, racist clown. That goes for his supporters, too. Empathy is not the game here.

The title has a double meaning: the trees from which the victims of lynchings were hung, and the family trees that link the living to the perpetrators of past atrocities. Everett is a writer of broad range and sweep, an author of cerebral realist metafictions (So Much Blue), Westerns (God’s Country), and bracing comic jeremiads (Erasure). (It might be more accurate to say that his books tend to be hybrids partaking of these genres and others.) When the New York Times reported last spring that he had given his publisher his new manuscript, a book “about lynching,” it was three weeks before the killing of George Floyd. The Trees, though it features spontaneous uprisings across the country, isn’t an answer to last year’s mass protests, but the book and the movement spring from the same bitter sources.

Are the killings in Money the work of a ghost? A zombie? Was the Black corpse even dead? Is it Emmett Till returned from the grave? These questions are too much for the town’s police force, a handful of incompetent racist yokels led by Sheriff Red Jetty and his deputies Delroy Digby and Braden Brady. The story goes viral, and the sheriff is reprimanded by Mayor Philworth Bass because he’s getting heat from the state capitol. “Mr. Mayor,” Jetty responds, “this here is the sovereign state of Mississippi. There ain’t no law enforcement, there’s just rednecks like me paid by rednecks like you.”

Not quite. Two Special Detectives from the MBI (Mississippi Bureau of Investigation), both of them Black, are dispatched to take over the case. Jim Davis and Ed Morgan are long-suffering middle-aged cops making their way among the hillbillies. Unlike most of the characters in this book they haven’t been given silly names. Ed, six-foot-five and three hundred pounds, drives the pair around Money in his own aging Toyota Sienna, because the minivan fits him, unlike state-issued cars. Jim is smoother and might just be flirting with the waitress at the local diner (called the “Dinah”) whose name tag reads “Dixie” but is really named Gertrude and might not be what she seems in other ways too. Ed and Jim are soon joined by an FBI agent, Herberta “Herbie” Hind, also Black, and they discuss why they became cops, as Ed and Jim answer in unison, with a fist bump: “So Whitey wouldn’t be the only one in the room with a gun.”

Most of the white characters in this novel are guilty: even if they are merely the descendants of the perpetrators of lynchings, they are unrepentant racists (or “know-nothing, pre–Civil War, inbred peckerwoods,” as one character puts it), frequent users of the N-word (with the hard r), stealers of livestock, or members of a pathetically diminished Ku Klux Klan. The racists are present all the way up the chain of American power: through the FBI, represented by an elderly agent from Dallas named Hickory Spit, “famous for leading the FBI efforts to discredit Martin Luther King, Jr., having once penned a letter to King suggesting that he commit suicide” (it’s believed the actual author of the letter was FBI deputy director William C. Sullivan: a copy was discovered in his files during the Church Committee investigation in 1976); through the government (a cabinet secretary and former senator from Alabama is murdered in the White House when the apparent copycat killings of lynchers’ descendants begins); to the president himself, first glimpsed cowering under his desk in the Oval Office after the killing of his cabinet member, getting gum in his hair, deposited under the desk by Mike Pence. Everett’s Trump delivers a televised address littered with the N-word, making a mockery of all the debates over whether he is “really” racist. Of course he is.

Not much present in The Trees are white liberals or leftists. The novel isn’t about them (us), unless perhaps it’s meant to flatter them with a vision of their redneck white-trash cousins getting a comeuppance at the hands of cunning and ruthless Black assassins (spoiler: the Black corpse is not the real killer, nor is it a ghost) and their Asian counterparts, avenging their own victims of lynching. Everett has had his go at white liberals elsewhere, most notably in Erasure, his satire of the publishing industry and the Quality Lit Biz. The Trees is looser and more freewheeling than that novel, Everett’s masterpiece, and many of its gags more disposable. There are many very funny throwaway lines. A recurring joke avers that characters named Ditka, McDonald McDonald, and Wesley Snipes are “no relation” to the football coach, the fast-food chain, or the actor: Wesley Snipes is a white police officer in Minnesota who loves Starbucks and disappears from the novel after two pages. The plot itself is constructed on deeper jokes, like the theft of a trailer full of years-old cadavers of unclaimed dead prisoners typically sold for medical use—a sacrilege all their own.

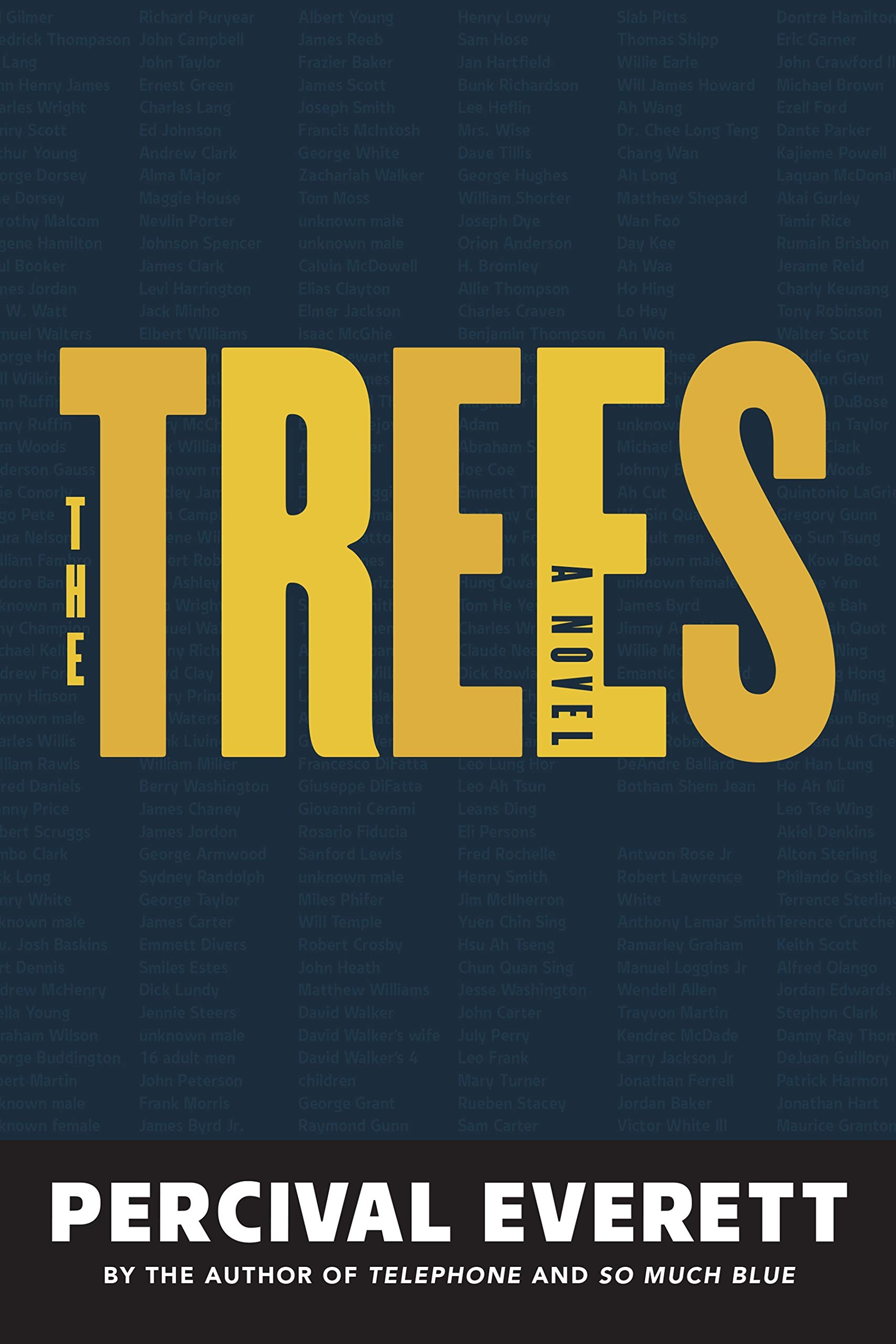

For all the absurdism, there is of course a serious strand to The Trees. A 105-year-old woman in Money called Mama Z, Gertrude’s great-grandmother, has kept meticulous files on the lynchings that have taken place since her birth in 1913. Gertrude summons an old college friend, Damon Thruff, an assistant professor at the University of Chicago, to study her archive and perhaps write about the recent killings. It’s here that an elegiac strain enters the novel: Damon writes down the names of the victims and they occupy pages of the text. In Mama Z’s archive, injustices forgotten by the culture are preserved for the reckoning chronicled in The Trees.

Another, more famous episode of violence is recalled when the detectives drive to Memphis and Ed takes a detour:

“Sorry about taking the long way,” he said. “It’s just that every time I’m in Memphis I have to drive by one place, not to get out, but just to pause and look.”

“Graceland?” Hind said and chuckled.

“I’ve been there, but no,” Ed said. “Here we are. The Lorraine Motel. There on that corner of that balcony. I was ten. That’s why I’m a cop.”

“It’s a museum now,” Jim said.

“And it shouldn’t be,” Ed said.

“Why not?” Quip asked.

“It’s just a motel. That’s what it is. That’s all it is,” Ed said. “People should rent out that very room and sleep in that very bed and step through that very door and stand on that balcony and realize what happened there. People should know, understand that not all Thursdays are the same.”

“Come on, Ed, let’s go,” Jim said.

The legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. isn’t exactly congruent with the campaign of revenge that sets off The Trees, but who wants precision from political allegory? By the novel’s end, the killings, with their disappearing cadavers, have swelled into an uprising that has the force of a weather system, or a new climate. America is on the edge of a cathartic second civil war, one where the revanchists are not at the advantage. It’s tempting to call The Trees the ultimate novel of the Trump era. It is the rare book that sees the forty-fifth president less as a menace here than a nuisance, the Republicans as so many falling elderly dominoes, and their white-supremacist voters a decrepit network of armed bozos. In that way, it’s also tempting to read The Trees as a hopeful book, but such a reading might also be naive. At the end, Damon is still typing out names, because the names of the dead keep coming, and history never stops.

Christian Lorentzen is a writer living in Brooklyn.