Gabrielle Bellot

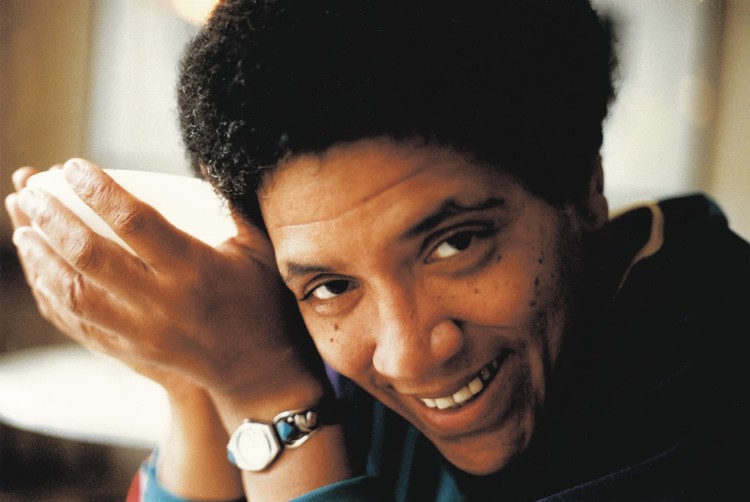

ONE DAY IN 1960, when she was thirteen, Octavia E. Butler told her aunt that she wanted to be a writer when she grew up. She was sitting at her aunt’s kitchen table, watching her cook. “Do you?” her aunt responded. “Well, that’s nice, but you’ll have to get a job, too.” Butler insisted she would write full time. “Honey,” her aunt sighed, “Negroes can’t be writers.”

ONE APRIL MORNING in 1973, just before dawn, a ten-year-old Black boy and his stepfather began to run through South Jamaica in Queens. A white policeman had pulled up in a Buick Skylark behind them, the crunch of the car’s wheels on the pavement interrupting the quiet semidarkness. Thinking the mysterious car contained someone who wanted to rob them, Clifford Glover and his stepfather fled. The cop, Thomas Shea, pulled out his pistol and fired into the boy’s back, killing him almost instantly. “Die, you little fuck,” Shea’s partner, Walter Scott, was recorded saying on a radio transmission, though he