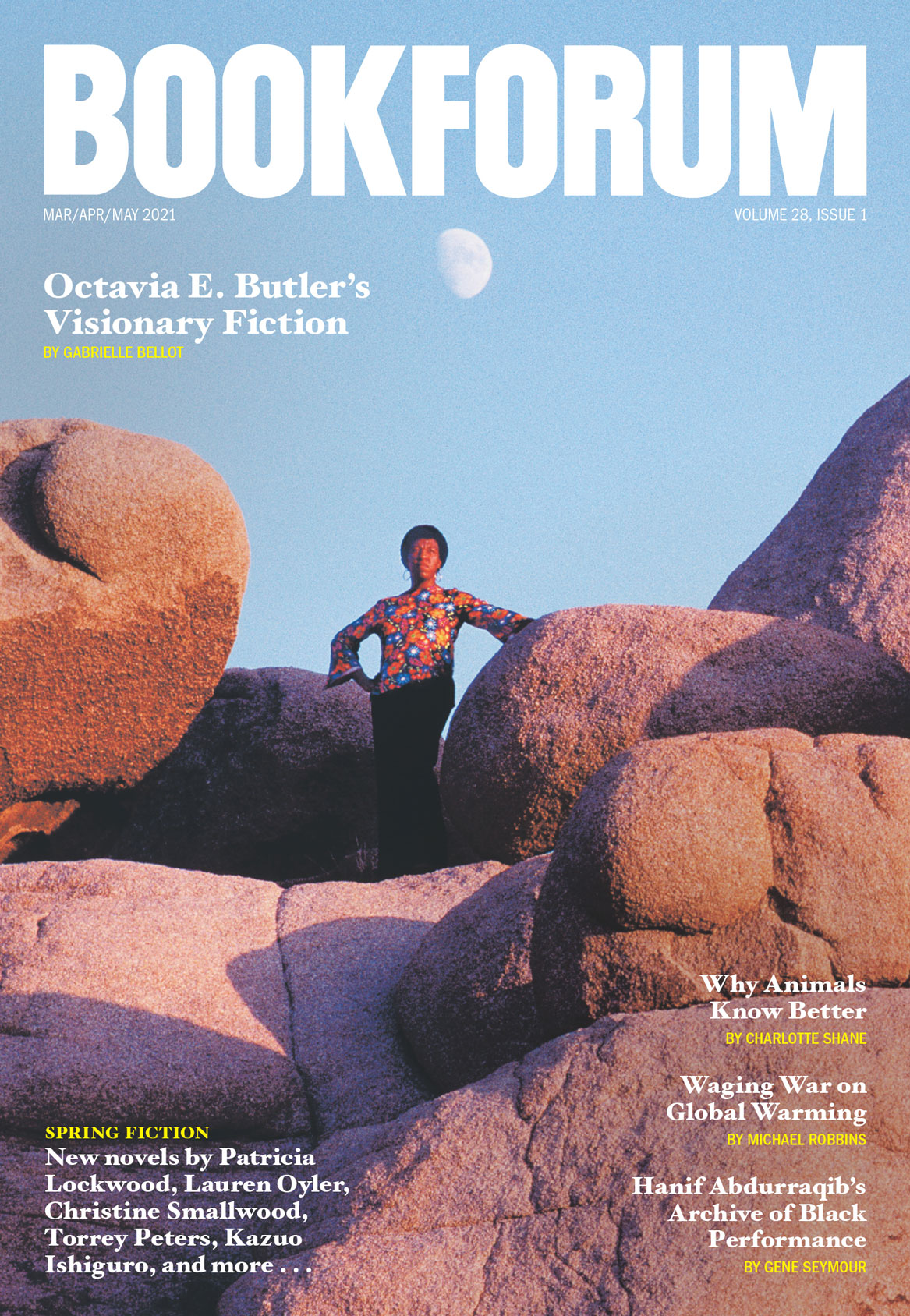

ONE DAY IN 1960, when she was thirteen, Octavia E. Butler told her aunt that she wanted to be a writer when she grew up. She was sitting at her aunt’s kitchen table, watching her cook. “Do you?” her aunt responded. “Well, that’s nice, but you’ll have to get a job, too.” Butler insisted she would write full time. “Honey,” her aunt sighed, “Negroes can’t be writers.”

“Why not?” Butler demanded.

“They just can’t.” The words chafed. For years, Butler had yearned to be a writer; it had never occurred to her before her aunt’s casual dismissal that her very identity might complicate things. As she later admitted in “Positive Obsession,” an autobiographical essay from 1989, her aunt’s reaction led her to realize something startling. “In all my thirteen years,” she wrote, “I had never read a printed word that I knew to have been written by a Black person.” Still, this dearth did not dissuade her; if anything, it made her want to have her writing published even more fervently.

And not just any writing, but science fiction, which she began to submit that same year to a slew of magazines. The year before, she had watched Devil Girl from Mars, a 1954 science-fiction B movie, and its remarkable mediocrity had astonished the writer in her. “Geez,” she’d said. “I can write a better story than that.” Ironically, this abysmal film became partly responsible for reshaping the world of American sci-fi, inspiring Butler to compose narratives that forever changed what was possible in the genre.

But it wouldn’t be easy, because in the 1960s, science fiction—which had risen in popularity as a distinct category throughout the twentieth century—was a field that rarely included anyone who looked like Butler. White men filled both its ranks of authors and their stories. Twenty years earlier, the sci-fi writer Isaac Asimov had gone so far as to declare, in a series of sneering letters in Astounding Science Fiction, that women had no place in such stories at all, as they were only there for “romance,” and he, like serious authors of his ilk, had no time for such expendable narrative distractions. “When we want science-fiction, we don’t want swooning dames,” he scoffed in one letter. “Notice, too, that many top-notch, grade-A, wonderful, marvelous, etc., etc., authors get along swell without any women, at all,” he declared in another from 1939. Fittingly, “Nightfall” (1941), one of Asimov’s seminal short stories, contained no women beyond passing references to them as child-breeders or siblings.

If the world of science fiction seemed lonely for someone like Butler, real life seemed lonelier still. She was painfully shy, and, as she grew older, she developed insecurities about her body that would linger. Classmates teased her about her voice, which had a notably deep, even masculine, rumble. This, along with her tallness—she would grow to six feet—made her easy fodder for schoolyard bullies. Boy, they called her, or lesbian. (In fact, Butler flirted with the idea that she might be gay or bisexual, but ultimately decided that she was “a hermit” rather than someone seeking romance of any kind.) She was a large, Black woman in a society that demonized being large, Black, or a woman, and although she enjoyed being alone, her sense of rejection never left. Aloneness, for those of us who understand its special, quiet pleasures, can be lovely; loneliness, however, is a louder, weightier thing, the uncomfortable presence of absence, a phantasmal weight Butler grew to know all too well.

Despite her isolation, she persisted, submitting short stories—though she considered herself a novelist first—and attending writing classes, even as those courses and their instructors reaffirmed the bigotry she was up against. In “Lost Races of Science Fiction,” a blunt 1980 essay on the absence of nonwhite characters in the genre, Butler recalls a telling moment in her first year of college: “I sat in a creative writing class and listened as my teacher, an elderly man, told another student not to use black characters in his stories unless those characters’ blackness was somehow essential to the plot. The presence of blacks, my teacher felt, changed the focus of the story—drew attention away from the intended subject.” Whiteness and maleness, ergo, were the default, apolitical places in which stories should begin; to do anything else was to distract from the plot.

Butler, as adamant as she had been that day in her aunt’s kitchen, defied this dictum, composing an array of arresting fictions that frequently featured Black protagonists whose race mattered. At the time, she was, along with Samuel R. Delany, one of the only African American sci-fi writers with any visibility, and until the twenty-first century, she was one of the only Black women writing in the genre. “As far as I know,” she mused in “Positive Obsession,” “I’m still the only Black woman who does this. . . . A young Black woman once said to me, ‘I always wanted to write science fiction, but I didn’t think there were any Black women doing it.’” Butler, then, was not only a successful author, but an overt argument for why representation matters in allowing future generations to feel that they, too, can do something.

And her novels were unabashedly tied to Black American life, viewed through a faintly fantastical lens. In the time-travel novel Kindred (1979), her best-known book, a twentieth-century couple—a Black woman and her white partner—are suddenly warped into the days of slavery, forcing both to grapple with a world in which their racial statuses are even more starkly opposed; in the later Fledgling (2005), an iconoclastic vampire novel, the half-human protagonist, Shori, is one of the only dark-skinned members of her kind, which both helps her—she can withstand sunlight better than her pale kindred—and makes her a target of other, more terroristic vampires who despise her differences.

Though she did not always explicitly tackle race in her fiction, much of her work was about what lies at the root of racism: a profound fear of the Other, whether extraterrestrial or simply someone not-of-our-tribe on this planet. Though Butler was lonely and rarely had lasting interpersonal relationships in real life, her characters often display deep, complicated connections with the beings around them, human or otherwise. Butler loved exploring the experience of encountering the alien: the way touching something unlike us might feel to us and to them, or how it would feel, as humans, to live in mutualistic relationships with other species. In simple but captivating prose, these provocative, probing stories sought to uncover what it might be like to exist amid Difference itself. Butler brought the stars, in all their fatal heat and fatalistic beauty, closer to us, as if to say, Look at them as if you have never seen them before.

BUTLER’S WIDE-RANGING CAREER as one of the earliest successful African American sci-fi writers is on full display in a capacious new collection from the Library of America, which features two novels—Kindred, published when she was in her early thirties, and Fledgling, the last book she published before her death the following year—as well as an array of short stories and essays, allowing both fans of Butler and those unfamiliar with her work to gain an impressively broad view of her oeuvre. The collection offers work from the beginning, middle, and end of Butler’s life, and its brief but potent selection of essays is a wonderful addition for readers primarily familiar with Butler as a fiction writer. Perhaps most important, this collection presents some of Butler’s most overtly race-conscious fiction, arriving at a time when the red scar of racism is arguably more visible than it has ever been this century, allowing the anthology to become a part of the country’s urgent reflection on the astonishing depths of its racist past and present.

The new collection also offers a short but sharp introduction by Nisi Shawl, as well as a series of “afterwords” by Butler. While brief, these postscripts show Butler’s thought processes behind, as well as the raisons d’être for, these stories and essays. Some are simple, almost journalistic revelations, like Butler’s declaration that she never liked the title, “Birth of a Writer,” that Essence magazine gave her story “Positive Obsession” when it first appeared—or her humble acknowledgment that “the best and the most interesting part of me is my fiction.”

Others cast Butler’s narratives in a new light: we learn that a peculiar short story, “Amnesty,” was influenced by the plight of Taiwanese-American scientist Wen Ho Lee, who was accused by the American government in 1999 of stealing documents pertaining to nuclear weaponry from Los Alamos laboratory. Back then, Butler writes, “I could still be shocked that a person could have his profession and his freedom taken away and his reputation damaged all without proof that he’d actually done anything wrong. I had no idea how commonplace this kind of thing could become.” The note, while concise, sharpens the themes of the story, which presents a vision of Earth in which Communities—sentient clusters of alien life that resemble moving bushes—have come to our planet and forced humankind to live alongside them in a kind of reluctant symbiosis. A number of human governments, the narrator reveals at the end, have clandestinely attempted to obliterate the aliens with nuclear strikes in an operation few civilians know about, an idea obviously related to Lee’s narrative. The strikes failed, however, and the Communities simply “returned” half of the missiles, “armed and intact,” to various cities around the world, rather than retaliating with violence.

“Apparently,” the narrator relates, “the Communities still have the other half—along with whatever weapons they brought with them and any they’ve built since they’ve been here.” This, then, is the twist ending, that the much misunderstood and maligned aliens have weapons, but have never used them (though they unintentionally hurt many humans in their early days, because they did not understand who or what we were, and “abducted” us for “study”). The unstable sense of peace between the humans and the Communities is maintained by the unspoken threat of war.

If this seems disquieting on multiple levels—our planet has been invaded by aliens, and we have immediately tried to eradicate them with nuclear missiles—this was Butler’s intention. She sought to disturb, in part because she had witnessed so much that shocked and shamed her. Shawl calls the Library of America collection a “canonization of discomfort,” and the description is apt, capturing both Butler’s own hurt and the discomfort she wished her readers to feel in turn. Kindred, which forces the reader to experience the horror of suddenly being a Black woman in the days of legal American slavery, emerged as a response to, if not an abstract portrait of, the pain her mother had endured, which the author shared in a revealing interview in 1991 with Randall Kenan. “My mother did domestic work and I was around sometimes when people talked about her as if she were not there,” she said. She continued:

I got to watch her going in back doors and . . . I spent a lot of my childhood being ashamed of what she did, and I think one of the reasons I wrote Kindred was to resolve my feelings . . . Kindred was a kind of reaction to some of the things going on during the sixties when people were feeling ashamed of, or more strongly, angry with their parents for not having improved things faster, and I wanted to take a person from today and send that person back to slavery.

In Kindred, readers experience what it is like to be seen not as a person but as a thing, an emblem of alienness—and, just as the narrator loses a limb by her horrific journey’s end, the reader, too, is expected to have lost any sense that America’s racist history (and present) can be glossed over.

IT WAS SUBVERSIVE IN BUTLER’S DAY, and remains so now, to depict nuanced relationships between humans and other species that cross into the territory of the sensual, if not the romantic, yet Butler was unsparing in her exploration of what it would be like to truly live with someone, or something, entirely unlike ourselves—at least on the surface. In so much of her fiction, Butler shows that it is possible to form multilayered relationships with the Other, in any form: human, vampire, colossal intelligent insect, alien colony. No matter how different we appear, we may be able to live together—and not simply coexist, but cooperate, if not cohabitate. We may even learn to love it. Butler’s preferred relationship structure in these stories was mutualism, whereby each member, at least in theory, benefited from the other, though in reality there were often complicated power dynamics at play.

For example, the Ina, or vampires, in Fledgling envenom the people they bite; the venom, an addictive drug, creates intense sensations of bliss and, over time, can prolong a human’s life by centuries. Once addicted, they will quickly die if they stop receiving it. In “Amnesty,” the Communities “enfold” people by covering them, a sensation that both humans and aliens generally enjoy. “The Communities feel better when they enfold us,” the narrator says. “We feel better too.” Yet the Communities, if uncertain about the person they are holding for any reason, may briefly electrocute them or tighten their many-pronged grip. Trying to escape during such moments might prove fatal—a dynamic that feels inescapably reminiscent today of police interactions with those of us who aren’t white, whereby we may be shocked or shot without warning, and an attempt to escape only exacerbates the likelihood of a lethal response.

Perhaps most horrifically, Butler’s most famous short story, “Bloodchild,” features a seemingly beneficent relationship between humans—“Terrans”—and large insect-like aliens called the Tlic. The Tlic offer their eggs, which, like Ina venom, prolong life, to the Terrans in exchange for the promise that humans will carry the Tlic’s young inside them. The arrangement seems anodyne to the narrator until he sees the grotesque spectacle for himself: humans ripped open, grubs wriggling in their flesh.

These relationships seem mutualistic, but they often have the darker undertones of a profound power imbalance. This is precisely what makes them feel viscerally, macabrely realistic in a way that is striking even today. We are organisms, Butler wished readers to remember, in a world of biological relationships; we can learn to live with that which is utterly alien to us, and even love it, but not all relationships that seem balanced on the surface truly are. There is no criticism of the aliens in these tales; they simply are what—and who—they are, and their customs, while grotesque to humans, are made to seem normal within the world of the story. This is Butler’s grandest power—to make readers feel like they have stepped into another world.

And aliens stepping into our world, Butler mused in “The Monophobic Response,” a brief but memorable speech on science fiction, might well, sadly, be the sole thing that unites us. “Perhaps for a moment, only a moment,” Butler wrote of the prospect of a real-life alien invasion, “this affront will bring us together, all human, all much more alike than different.” In the beautifully resonant final sentence of the essay she asked: “What will be born of that brief, strange, and ironic union?”

In an America more profoundly disunited than ever, her question still echoes in the night. Yet her fiction comes close to posing the complex answers, presenting worlds in which difference and sameness are never simple propositions but the foundations for remarkable, robust new relationships. Butler called out bigotry unflinchingly; she also imagined futures in which we have so thoroughly dismissed the crude prejudices of racism, sexism, and anti-queerness that we can learn to embrace that which seems Other, such that it ceases to be Other at all. The same Butler who was once told that she could never live as a writer now speaks poignantly to an America—so starkly polarized as to seem like two separate planets whose races, unlike in Butler’s fiction, have failed to coexist—that needs her blunt but empathetic vision more than ever.

Gabrielle Bellot is a staff writer for Literary Hub and an instructor and editor at Catapult.