Hussein Ibish

The last thing most Americans wanted during Barack Obama’s second term was another war in the Middle East. But now we’re in one, and an inevitable and necessary raft of new books is emerging to explain to the public how and why this came to be. Patrick Cockburn’s The Rise of Islamic State is an important contribution to this topical genre, even though his account is deeply flawed in key respects. It is, at best, half the story, and readers will have to look elsewhere for a more comprehensive and balanced assessment. Fanaticism has an unerring ability to undermine its most cherished values. The fanatic’s fog of irrationality and rage typically renders him (and the most powerful fanatics are reliably hims) not only incapable of successfully pursuing imagined goals, but often only effective in damaging or destroying them. The thugs who broke into the offices of the satirical French magazine Charlie Hebdo yesterday and murdered twelve people in the name of God and religion no doubt imagined that they were “avenging blasphemy.” But in reality, they committed an act of supreme blasphemy. They insulted, traduced, and denigrated the Prophet Muhammad, Islam, and

As this review was going to press, the latest bout of hostilities between Hamas and other Gaza-based militants and Israel had become even more bloody and destructive than 2009’s brutally named Israeli incursion into Gaza, Operation Cast Lead. An estimated 1,700 people have been killed. Between 70 and 80 percent of them were Palestinian civilians, and at least 200 were children. Israel has so far attacked seven UN schools serving as refugee shelters, provoking harsh condemnation even from the United States. Meanwhile, Hamas has drawn criticism from the global community for using abandoned schools to store ordnance. Sixty-four Israeli troops

Henri Lefebvre’s notion of “Revolution as Festival,” which the great French political thinker developed in his account of popular uprisings of the twentieth century, continues to inspire today’s global Left and its ideas of “people power.” Cultural theorist Gavin Grindon cannily sees this vernacular spirit of celebration in “the global cycle of social struggles since the 1990s, from Reclaim the Streets to the Seattle World Trade Organization Csarnival Against Capitalism, Euromayday and Climate Camp to Occupy’s Debt Jubilee.” And this same narrative—which at times approached a shared, lived reality—informed many domestic and international perceptions of the early “Arab Spring” uprisings

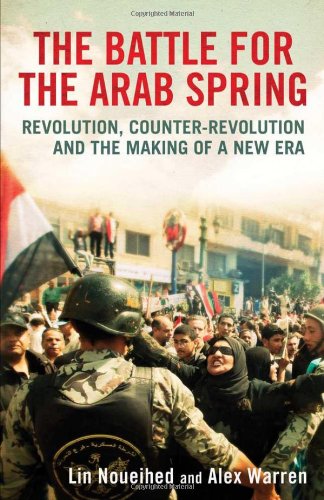

If anybody asked me, particularly in a plaintive tone of desperation, for a comprehensive backgrounder on the uprisings that have convulsed much of the Arab world since December 2010, I’d have no hesitation in pointing them to The Battle for the Arab Spring. Lin Noueihed, a Reuters editor, and Alex Warren, a consultancy expert, have joined forces to produce a remarkably far-reaching and exceptionally precise summary of the uprisings generally, but unfortunately, referred to as the “Arab Spring.” Particularly for the uninitiated or those seeking a synoptic but relatively detailed account of what has and hasn’t happened in the Arab American foreign policy in the Middle East has reached one of those moments at which almost everyone agrees that things are going badly but no one can agree what to do about it. Passionate disputes regarding the American approach toward Iran make this lack of consensus abundantly plain. On one extreme, neoconservatives such as Norman Podhoretz demand war with Iran at once, some even saying it is long overdue. On the other side, a growing chorus, both liberal and conservative, argues that war with Iran is not an option given its high costs and limited benefits; instead, they counsel containment

Americans and Libya go way back. The opening lines of the “Marines’ Hymn” commemorate the First Barbary War (1801–05), one of the young republic’s earliest forays into international military intervention. During the Reagan era, Libya and its dictator, Muammar Gaddafi, became synonymous with terrorism for many Americans, after the Libyan-sponsored bombing of a West Berlin nightclub frequented by US soldiers. This mistrust was famously dramatized in Back to the Future, in which the panicked cry “The Libyans!” was intended to be both bloodcurdling and somewhat absurd. And during the last presidential election, the word Benghazi summarized the Republicans’ attacks on