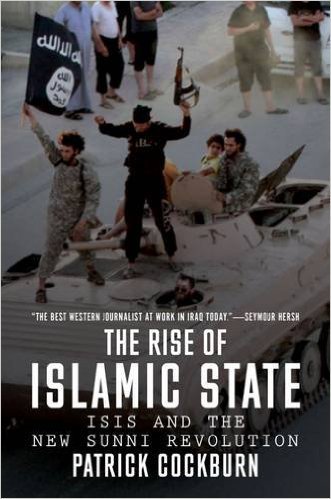

The last thing most Americans wanted during Barack Obama’s second term was another war in the Middle East. But now we’re in one, and an inevitable and necessary raft of new books is emerging to explain to the public how and why this came to be. Patrick Cockburn’s The Rise of Islamic State is an important contribution to this topical genre, even though his account is deeply flawed in key respects. It is, at best, half the story, and readers will have to look elsewhere for a more comprehensive and balanced assessment.

Obama swept into office in 2008 in large measure because he vowed to end the indefensible, almost inexplicable war in Iraq and the ill-conceived nation-building project in Afghanistan, both initiated by his predecessor, George W. Bush. During his first term, Obama took major strides toward fulfilling this promise. Voters expected that his administration would continue to disengage the United States from these regional quagmires after his 2012 reelection, while simultaneously conducting an expanded counterterrorism campaign against Al Qaeda.

But early this past summer, Americans suddenly found themselves once again embroiled in a long-term conflict with a Middle Eastern group most of them had never heard of: the Islamic State, also known as ISIS (or ISIL). This violent faction is an offshoot of the organization known as Al Qaeda in Iraq, which had gradually been subdued with the help of local Sunni Arab forces during the “Sunni Awakening” of 2007. ISIS gained great momentum and increasing popular support during the chaos of the Syrian civil war, and in 2013 it won control of Raqqa, the only regional capital completely outside the reach of the dictatorship of Bashar al-Assad. In 2014 it swept into Iraq, seizing control of much of the Sunni-majority western provinces, including major cities such as Mosul and Falluja. Its assets and criminal enterprises reportedly now bring in an income of between $1 million and $3 million daily, which probably makes it the richest terrorist organization in human history.

In August, ISIS forces were threatening the Kurdish regional capital Erbil, home to many American offices and expatriates, and had isolated thousands of Yazidis, a religious minority, on a remote mountainside, where they faced imminent death. The humanitarian mandate to shield the Yazidi population overlapped with the narrower concern of protecting American interests, and so Obama approved a series of air raids against ISIS fighters. The terrorists responded by beheading American hostages and releasing gruesome videos on the Internet. While American war planners sought to limit the scope of the initial anti-ISIS raids to extremely focused objectives, the campaign has taken on a life of its own, with unmistakable signs of mission creep. Many Americans now grasp that their country has once again embarked on an open-ended Middle Eastern campaign to “degrade and ultimately destroy” the capabilities of a well-funded terrorist and criminal enterprise.

In The Rise of Islamic State, Cockburn sets out to explain how ISIS became enough of a threat to prompt even the risk-averse Obama administration to initiate another bout of military action in the Middle East. At first glance, Cockburn, the Middle East correspondent for the London Independent, seems ideally suited to the task. He’s been reporting on Iraq for more than a decade and on other conflicts in the region for much longer. This experience shines through in his thumbnail guide to the rise of ISIS forces in Iraq over a hundred-day period, a useful device for conveying to Western readers just how rapidly and stunningly the terrorist group redrew the map of the Middle East in the first half of 2014.

Cockburn emphasizes that the armed forces seeking to overthrow the Damascus dictatorship are “dominated by jihadis who wish to establish an Islamic state.” He lays out this analysis by focusing on the conflicts in eastern and central Syria, an approach that is undoubtedly well-founded, but that largely ignores conditions in the South, where the situation is more complex. He contends that the success of ISIS has been so sweeping that the “more secular Free Syrian Army (FSA) . . . has been marginalized.”

Conceding, for the sake of argument, that Syria’s anti-Assad opposition has indeed marginalized all nonjihadist groups, this was the outcome, rather than a prior condition, of the West’s intervention in the Syrian crisis. So how did this dramatic shift happen? Cockburn dismisses any suggestion that the radical-Islamist leaders of ISIS occupied a strategic vacuum created by Western neglect of nonextremist and nonsectarian elements in the opposition. Indeed, he waves away the prospect that moderate rebels were left to twist in the wind in Syria, for the simple reason that he doesn’t buy into their existence. “In reality, there is no dividing wall between [ISIS forces] and America’s supposedly moderate opposition allies,” he writes, adding, “arms supplied by US allies such as Saudi Arabia and Qatar to anti-Assad forces in Syria have been captured regularly in Iraq.”

By contrast, a whole host of former Obama-administration officials have concluded that the reluctance of the United States and its allies to promote less-extreme groups in Syria led directly to the rise of ISIS. Among the advocates of this view are Hillary Clinton, Leon Panetta, Robert Gates, David Petraeus, and now, recently departed defense secretary Chuck Hagel. And many close observers of the region both within and without the foreign-policy establishment have long warned that if the United States and its allies did not take action to shape the course of the Syrian conflict, others would, to the detriment of American interests. This rather obvious scenario has played itself out with dark inevitability. But Cockburn has no patience for such arguments and elects either to ignore them or dismiss them implicitly.

The Rise of Islamic State furnishes a clear-eyed survey of how other crucial policy miscues have added to this lethal blowback. Cockburn meticulously documents how the failures of the American-led “war on terror” and the allied myopia of the Iraqi government of Nouri al-Maliki helped fuel ISIS’s ascendancy. But he never applies the same critique to the sectarian minority government of Assad, whose policies have alienated Syrian Sunnis at least as much as Maliki’s have their Iraqi counterparts. Cockburn similarly fails to note that the initial phase of the uprising against Assad, spurred on by the Arab Spring protests of 2011, was largely peaceful and nonsectarian; it was, crucially, the Assad regime that labored mightily to ensure that the opposition became as violent, extremist, and sectarian as possible. Cockburn cites but then dismisses an International Crisis Group report from July 2011 that noted, in fairly mild terms, the Assad regime’s role in stoking violent sectarian resistance. Instead, Cockburn insists that the Syrian opposition’s disastrous collapse into Islamist militancy came under “the thumb of foreign backers,” particularly the Gulf states, which supposedly created this vicious “movement wholly controlled by Arab and Western intelligence agencies.”

[[img]]

It is extraordinary to read an account of the rise of Sunni extremist groups in the context of the war in Syria that all but ignores the Syrian regime’s murderous response to popular protests calling for reforms and elections. Any serious history of how the Syrian uprising became armed, sectarian, and radicalized would have to give at least as much attention to the Assad regime’s brutal abuses: its extensive use of torture and its deployment of chemical weapons and virtually every kind of conventional armament against rebels and civilians alike. All these measures, and many others, have killed more than 200,000 people in just three years. Assad’s repressive policies have exiled or displaced approximately ten million people—seven million within the regime’s borders and three million more in Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, and elsewhere.

By so completely neglecting the centrality of Assad’s regime in radicalizing the Syrian opposition and facilitating the ascent of ISIS, Cockburn’s narrative tilts unpersuasively toward the outsize role of regional actors beyond Syria’s borders. He attributes ISIS’s rise almost entirely to the extremism of Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states that have backed the Syrian opposition (even though these states have all enlisted—however unenthusiastically—in the American-led anti-ISIS coalition). But no chronicle of the ISIS conflict can be complete without a serious evaluation of how the extremism of the regime helped mold the extremism of the opposition.

Cockburn dwells at greater length on the detail, repeated several times throughout The Rise of Islamic State, that fifteen of the nineteen hijackers responsible for the 9/11 terrorist attacks were from Saudi Arabia than on the punitive actions of the Assad regime in the critical early phase of the Syrian uprising. He writes as if supposed (or indeed real) Saudi attitudes were more important in shaping the course of the Syrian civil war than the lived experiences of the majority of Syrians under a particularly vicious and unrestrained dictatorship.

Other books on ISIS will have to take up that essential part of the story. Cockburn’s readers will find a good deal of valuable information and some suggestive insights into the longer-term ironies of American interventionism. But if they read this book and no other account of the ISIS insurgency, they will come away with an exceptionally incomplete and distorted understanding of the war in Syria and the terrorist menace it engendered.

Hussein Ibish is a weekly columnist for The National (UAE) newspaper and NOW media and a frequent commentator on Middle Eastern affairs for a wide range of Arab and American media.