Kate Bolick

“Little Women was about the best book I ever read.” So began my fourth-grade book report, in 1981. Clear, if uninspired. After one-and-a-half double-spaced pages of cursive rhapsodizing in support of this daring claim, I concluded with the lazy feint of an already overburdened critic: “I would like to go on and on with this report but it would be longer than the book, so if you want to find the rest out my opinion is to read it.”

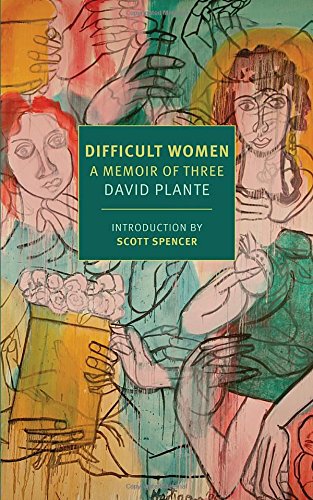

It is obvious why David Plante’s “memoir” Difficult Women, about his “friendships” with three prominent figures in the 1970s, found a publisher the first time around. (More on the scare quotes shortly.) Back then, in 1983, two of his subjects—novelist Jean Rhys and literary executor/professional widow Sonia Orwell—were newly dead, and famous mostly within intellectual circles, giving the book insider appeal, while the third, the always larger-than-life writer and feminist Germaine Greer, who’s had the dubious luck of outlasting this book twice now, granted a dollop of commercial relevance. Or so one imagines a publisher calculating.

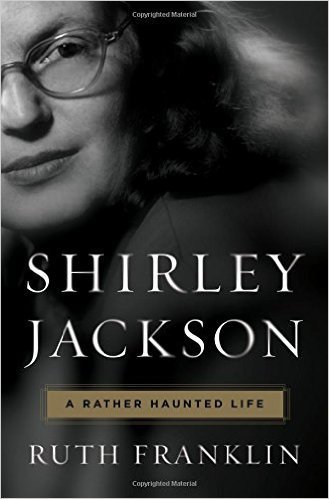

Shirley Jackson’s legacy might not seem in need of assistance. Fifty-one years after her death, nearly all of her books are in print, and her most celebrated works—“The Lottery,” possibly America’s most famous short story, and the novels The Haunting of Hill House, twice adapted for film, and We Have Always Lived in the Castle, which just went into production after years of stalling (talk about sating a renewed appetite for complicated female leads!)—continue to send chills down spines. In 2010, the Library of America enlisted Joyce Carol Oates to honor Jackson with a best-of volume, and earlier this year