Shirley Jackson’s legacy might not seem in need of assistance. Fifty-one years after her death, nearly all of her books are in print, and her most celebrated works—“The Lottery,” possibly America’s most famous short story, and the novels The Haunting of Hill House, twice adapted for film, and We Have Always Lived in the Castle, which just went into production after years of stalling (talk about sating a renewed appetite for complicated female leads!)—continue to send chills down spines. In 2010, the Library of America enlisted Joyce Carol Oates to honor Jackson with a best-of volume, and earlier this year Paul Giamatti, A. M. Holmes, and other notable enthusiasts celebrated the centennial of her birth with readings at New York’s Symphony Space. The sinister artistry of this “Virginia Werewolf among the séance-fiction writers,” as Time magazine campily called her in 1962, holds up.

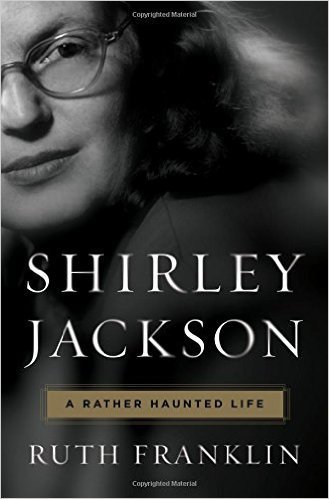

Hocus-pocus puns were something of a professional liability for Jackson, thanks in no small part to her publishers, who eagerly played up her interest in black magic; early jacket copy lauded her as “perhaps the only contemporary writer who is a practicing witch.” Jackson herself liked to tell her children she was born knowing how to read Tarot cards. Such fun and games surely sold books, and yet, as a smattering of critics and scholars has pointed out over the decades, filing her under “horror writer” drastically undersells her contribution to American literature. Jackson’s most genuinely uncanny talent was the way in which she channeled the nation’s postwar tensions and hypocrisies—particularly those around class, race, gender, and anti-Semitism—into fiction so unputdownable that most readers don’t even see the cultural critique just beneath their noses. Articles and academic books only go so far in setting a record straight, however. To truly reclaim a legacy, it generally helps to have a big, penetrating biography, one that takes into consideration everything that’s come before and pushes forward a new and improved interpretation. Ruth Franklin’s excellent Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life is all that and more.

If you’re a Jackson fan, chances are you remember the houses described in her stories and novels. Turreted, brooding, maternal, malevolent, these unforgettable structures are “the gravitational center of much of her fiction,” Franklin writes, and place her squarely within the Gothic tradition, where, of course, most people have been content to leave her. Franklin, an accomplished critic, traces the “technique of using houses and their furnishings as expressions of psychological states” back to Jackson’s first novel, The Road Through the Wall, published in 1948. But she also expertly connects the dots between Jackson’s creative fixations, private travails, and larger, social-historical context, to show that the houses serve not only as characters in their own right, and metaphors, but also as a sophisticated symbolic critique of the female condition at midcentury. “Two decades before the women’s movement ignited, Jackson’s early stories were already exploring the unmarried woman’s desperate isolation in a society where a husband was essential for social acceptance,” Franklin explains. “As her career progressed and her personal life became more troubled, her work began to investigate more deeply the psychic damage to which women are especially prone.” Here, then, is Jackson’s (and Franklin’s) big reveal: “Her body of work constitutes nothing less than the secret history of American women of her era. . . . A powerful counternarrative to the ‘feminine mystique,’ revealing the unhappiness and instability beneath the housewife’s sleek veneer of competence.”

I really hope that Betty Friedan is rolling over in her grave right now. For all her perspicaciousness in The Feminine Mystique (published in 1963, two years before Jackson’s death from cardiac arrest at forty-eight), Friedan admonishes Jackson and her ilk—“Housewife Writers,” she sneers—for the ways in which they “deny the lives they lead, not as housewives, but as individuals.” Friedan is referencing not the “serious” fiction Jackson published in the New Yorker, but the very funny domestic essays she contributed to women’s magazines such as Ladies’ Home Journal and Mademoiselle, collected as the widely beloved Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons (both were reissued last year). In these comic sketches, Jackson chronicled the pleasurable chaos of raising a family—little Sarah’s “unceasing, and seemingly endless, war against clothes, toothbrushes, all green vegetables, and bed”; nine-year-old Laurie’s observation, on the birth of Jackson’s last child, Barry, that his mother has “something to keep you busy now we’re all grown up”—because it was fun, and she was good at it (Franklin calls her a forerunner of today’s “mommy blogs”), and also because, as the primary breadwinner in a dual-income household of two adults, four children, and many cats, she was under constant financial pressure. In an industry slavishly devoted to policing the boundary between intellectual credibility and commercial appeal, many of Jackson’s (mostly male) critics simply didn’t know what to make of a writer who could successfully straddle this divide; rather than recognize her radical, original, cross-genre critique of the stay-at-home housewife’s claustrophobia for what it was, they dismissed it outright. “There is no reason, I suppose, why a mother should not write at some length about her four children. . . . But when that mother is a prose stylist of the caliber of Shirley Jackson it is something of a shock to read such ephemeral fluff,” concluded one such columnist about Life Among the Savages. Friedan was even more displeased, going so far as to argue that, by encouraging real housewives to laugh at the trap that was their lives, the Housewife Writers weren’t all that different from Amos and Andy, or Uncle Tom. There’s a satisfying irony, then, to how adroitly Franklin proves that Jackson diagnosed the loneliness and personal alienation of women confined to the home, with no identity apart from a husband and children—Friedan’s so-called “strange stirring”—long before the feminist icon did.

Jackson never identified as a feminist—few women did during the long, dark 1950s and early ’60s—and Franklin doesn’t try to make her into one. She does, however, show Jackson’s commitment to racial justice in the years before the civil-rights movement, as well as the hypersensitivity to anti-Semitism she acquired by rejecting her WASP upbringing and marrying a Jew, the literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman, at a time when interfaith coupling was still considered unacceptable. Meanwhile, of course, Jackson was a woman during America’s flamingly sexist midcentury, who managed to be a devoted wife, loving mother, and famous writer—all at the same time. (Aspiring have-it-all-ers, take note: Jackson subscribed to the “good enough” theory of housekeeping—that is, who cares if the sofa reeks of cat piss? Indeed, as Franklin points out, “More often than not, housekeeping done too perfectly in one of her stories is a sign that something is amiss.”) Jackson was not only far more politically aware than she’s usually given credit for, she was also, in contemporary parlance, a badass, a proto-feminist in a floral housedress.

Franklin is not Jackson’s first biographer. Judy Oppenheimer, whose Private Demons came out in 1988, did a very good job chronicling the vicissitudes of Jackson’s too-short life, from her beginnings in California to her end in Vermont, tracing the crippling influence of her small-minded, deeply conventional mother and the uglier aspects of her marriage to Hyman (who was unfaithful, self-centered, and more than a little resentful of his wife’s success). But, by remaining a touch too in thrall to Jackson’s mythmaking, Oppenheimer never gained the objective distance necessary to see the true nature of her subject’s genius, or her cultural significance. And so another generation came and went without Jackson receiving her rightful due.

Franklin proves to be a supple biographer. The opening chapters, about Jackson’s ancestral background, childhood, and adolescence, carefully track her early influences and interlace insightful references to the author’s adult works. Franklin’s treatment of Hyman is particularly sensitive. For all his failings as a husband, he provided his wife with the intellectual stimulation and family feeling that she craved and was an unflagging champion of her writing, which couldn’t have been easy as the years passed him by and she eclipsed him time and again. Franklin also unearths a few surprises. One has to do with the true origin story of “The Lottery,” which she was able to piece together, detective style, through Jackson’s written correspondence with her agents, which previously hadn’t been available. Another discovery was a trove of late-in-life letters between Jackson and a fan, a housewife named Jeanne Beatty. The correspondence began just as Jackson embarked on We Have Always Lived in the Castle, and quickly became personal, offering new insights into Jackson’s inner life during that period—her recurring nightmares, tactics for writing-while-

mothering (“You will eat vegetable soup again today and like it; Mommy’s beginning chapter three”), her pride in her and Stanley’s friendship with Ralph Ellison, even an allusion to a romantic encounter with Dylan Thomas.

To my eye, Franklin’s most revealing material discovery was Jackson’s cartoons. As drawings, they’re not much to speak of—usually little more than a crude sketch paired with a caption—but as self-portraiture, they’re gold. In them, Jackson consistently depicted herself as a tall, soft triangle topped with a round disk from which six or seven long, squiggly strands of hair shoot out, as if she’s just stuck her finger in an electric socket. Given that, in real life, Jackson was indifferent to grooming and fashion, and struggled with her weight, it’s hard not to see the blank geometry of her body as a wishful erasure of her inconvenient femininity, and the unruly coif as a joke on herself. That said, between the prodigious imagination on display in Jackson’s books and Franklin’s portrait of the artist as a feverishly committed writer, known to vanish from her own dinner parties to type out a story, it’s also tempting to interpret that Einsteinian halo as a bouquet of wild ideas forever zooming from every lobe of her brain, or even—forgive me—psychic feelers quivering with spectral knowledge, not of the supernatural, necessarily, but of a reality the rest of us can barely sense, never mind see.

Kate Bolick’s first book, Spinster: Making a Life of One’s Own (Crown), was a New York Times Notable Book of 2015.