Lauren Elkin

Georges Perec once published an essay called “Brief Notes on the Art and Manner of Arranging One’s Books,” which confronts the “problem of a library”: how to classify one’s books when they so frequently defy categorization? What is a reliable way to arrange them so that you can lay your hand on the right one when you need it? Perec distinguishes between stable classifications and provisional ones, those that, “in principle, you continue to respect,” and those “supposed to last only a few days, the time it takes for a book to discover, or rediscover, its definitive place.” As a

For Virginia Woolf, the sounds of the streets of London formed a language of their own: “I stop in London sometimes, and hear feet shuffling. That’s the language, I think, that’s the phrase I should like to catch,” she wrote in an early draft of The Waves. Many poets who have written of London share this opinion, and a new anthology—London in Verse, edited by Mark Ford—reflects six-hundred years of the rich and heady language that they have chosen to describe their city: its rhythm, its pace, its stench; its people, their stench. “How do those who profess themselves to be abstract thinkers experience emotions, the body, and touch?” philosopher François Noudelmann asks in The Philosopher’s Touch: Sartre, Nietzsche, and Barthes at the Piano. In this lyrical essay on philosophy and music-making, Noudelmann contends that the piano provides another kind of “voice” for a philosopher, one that channels different rhythms and tones than those we hear in their writing and speech. And in understanding their music, we have a different means of understanding their philosophical outlooks. Drawing heavily on the philosophical discipline of phenomenology, Noudelmann’s highly original book shows that engaging with the

In Errol Morris’s new collection of essays on photography, he details the controversy over the New York Times’s misidentification of a torture victim in a notorious Abu Ghraib photograph. In the image, a hooded man draped in a poncho stands on a box, arms out, wires connected to his fingertips in an accidentally Christ-like pose. On March 11, 2006, the Times identified the man as Ali Shalal Qaissi—nicknamed “Clawman” because of his deformed left hand—and ran a photograph of Qaissi holding the by-then iconic photograph. Within a week, the paper printed a retraction explaining that Qaissi was not, in fact,

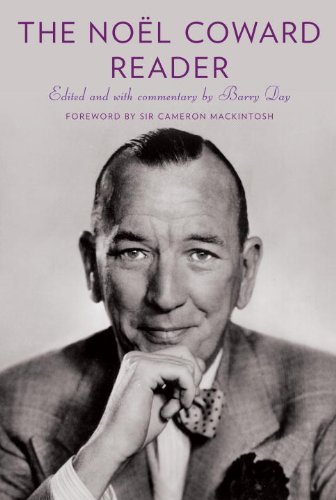

As the theater critic John Lahr once wrote, “Only when [Noel] Coward is frivolous does he become in any sense profound.” There’s proof of this throughout Barry Day’s new book, The Noel Coward Reader, a selection of Coward’s plays, lyrics, poetry, short stories, radio broadcasts, and excerpts from his diaries and letters. Here, Coward shifts between his “frivolous” best work, and his more serious (but less successful) attempts to make art that would endure beyond the tastes of the moment. As Day writes, Coward “was a great writer—except when he was trying to be a great writer.” In the preface to his translation of John Ruskin’s Sesame and Lilies, Marcel Proust wrote that while some people decorate their rooms with things that reflect their taste, he preferred his room to be a place “where I find nothing of my conscious thoughts, where my imagination is thrilled to plunge into the heart of the not-me.” Anyone who has stood looking at Proust’s reassembled cork-lined bedroom at the Musée Carnavalet in Paris—his armchair, his pigskin cane, his brass bed—and tried, unsuccessfully, to feel kinship with his spirit would be relieved to know that he had such a desultory relationship In his 2007 book, The Discovery of France, historian Graham Robb argued that the idea of a homogeneous people called “the French” was a myth carefully constructed to bring political and cultural unity to a “vast encyclopedia of micro-civilizations.” Now, in his new work, Parisians: An Adventure History of Paris, Robb depicts a Paris that is similarly “a composite place built up over the ages, a picture book of superimposed transparencies,” where “even the quietest street is crowded with adventures.” From the cabaret to the nightclub, from the theater to the ballet, women who perform in public have attracted writers and artists for as long as women have performed in public. Unlike the prostitute, who, as Walter Benjamin once said, is “saleswoman and wares in one,” the chorus girl is not exactly selling herself—she’s selling a dream of who she might be. The gaze that falls on her is sometimes male, sometimes female, sometimes singular, sometimes multiple. Onstage or off, the chorus girl is defined by her relationship to a necessary other—her audience—who, after all, may just be the reader. In 1913, the French writer Charles Péguy observed that “the world has changed less since Jesus Christ than it has changed in the last thirty years.” Kate Cambor’s new study, Gilded Youth, tracks the changes of that era through the figures of Léon Daudet, son of the beloved French writer Alphonse; Jean-Baptiste Charcot, son of the groundbreaking neurologist Jean-Martin; and Jeanne Hugo, granddaughter of Victor. These childhood friends, all born in the late 1860s, were caught between two epochs, between the “pessimism and pensiveness” of the nineteenth century and the “energy and activity” of the twentieth. Sigmund Freud, Émile Zola,