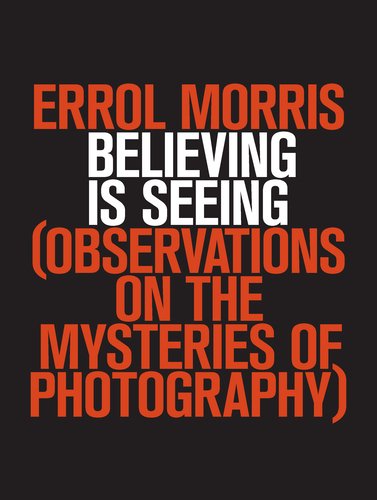

In Errol Morris’s new collection of essays on photography, he details the controversy over the New York Times’s misidentification of a torture victim in a notorious Abu Ghraib photograph. In the image, a hooded man draped in a poncho stands on a box, arms out, wires connected to his fingertips in an accidentally Christ-like pose. On March 11, 2006, the Times identified the man as Ali Shalal Qaissi—nicknamed “Clawman” because of his deformed left hand—and ran a photograph of Qaissi holding the by-then iconic photograph. Within a week, the paper printed a retraction explaining that Qaissi was not, in fact, the man in that particular photograph—the real hooded man is named Abdou Hussain Saad Faleh. As it happened, on May 22, 2005 the Times had correctly identified the man as Faleh; but when fact-checkers were trying to confirm the 2006 story, they missed the earlier article due to a faulty set of search terms. Morris suggests that this error occurred because of our willingness to believe what we think we see, regardless of available data. Had post-liberation photographs of Qaissi depicted his deformed hand, it would have been immediately apparent that the Hooded Man was someone else. “It is easy to confuse photographs with reality,” Morris writes, arguing that we look at this photograph and believe it to depict a moment of torture being carried out on a person we have since identified. “Our beliefs about the picture are confirmed” when we look at it, he adds, “except that we know nothing more than when we started.” “It is often said that seeing is believing,” Morris continues. “But we do not form our beliefs on the basis of what we see; rather, what we see is often determined by our beliefs. Believing is seeing, not the other way around.”

Morris, the Academy Award-winning director of documentaries such as The Thin Blue Line, The Fog of War, and the recently-released Tabloid, uses the methods he perfected while researching these films to piece together what really happened in a variety of controversial photographs, from a shot of a Mickey Mouse doll in the rubble of southern Lebanon to the disturbing photographs of Sabrina Harman flashing a thumbs-up and a beauty queen smile over the bloodied body of a deceased prisoner in Abu Ghraib. Morris shows that the way we look at photos is crucial to how we see—and understand—the world, and challenges the assumption of photographic veracity, especially in images of politicized subjects. “When does a photograph document reality?” Morris asks. “When is it propaganda? When is it art? Can a single photograph be all three?”

In seeking answers, Morris teaches us how to get closer to the ‘truth’ of a photograph. One essay tries to unravel a mystery concerning two 1855 photos taken by Roger Fenton during the Crimean War. The first image depicts a dusty road not far from Sebastopol, littered with cannonballs, while the second shows the same scene, but with the cannonballs off to the side. Did Fenton move them off the road or onto it? Through a painstaking analysis of shadows, light, and the position of rocks on the hillside, as well as a trip to Crimea, Morris finds his answer: in one of the two photographs, a group of rocks have moved downhill, making it clear that the cannonballs were moved onto the road for the second picture.

But why does it matter if Fenton staged the photograph? Morris has been criticized in the past for the re-enactment technique he employs in his documentaries, which he defends by appealing to common sense: there is no way that Morris could have been present with a film crew to have captured the events re-enacted in The Thin Blue Line. We know we’re watching something that’s been staged. When we look at a photograph, however, we don’t know the circumstances of its creation. “The Fenton photographs,” he tells us, allow us to confront “some of the most vexing issues in photography”: posing, the photographer’s intentions, photographic evidence, and “the relationship between photographs and reality.” There are many reasons for Fenton to have placed those cannonballs on the road in order to photograph them, and critics like Susan Sontag have faulted him for it, presuming that he did so in order to grandstand about the danger he was in as a war photographer in the Crimea. Other critics speculate that they might have been placed there for aesthetic reasons, to add texture to the road and make for a more interesting shot. What the truth is, we’ll never know.

When dealing with suffering and death, photography acts as a kind of testimony, and it may seem crucial that images remain unaltered if we are to believe what they tell us. However, as Morris contends in the essay “The Case of the Inappropriate Alarm Clock,” the “altered” photographs that Walker Evans took of Depression-era sharecroppers’ houses are somehow more “true” in their “simple” depiction of the way these people lived than the more sensationalist photographs Dorothea Lange took for the WPA, or James Agee’s “mannered” cataloguing of the contents of one of these households in “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.” Different kinds of documentation tell us different things about their subjects—”Everything in a photograph is possible evidence,” Morris writes. “It depends on the questions we are asking and trying to answer.” In war photography, we hope we are being shown an unvarnished view into an unimaginable reality. But Morris reminds us that photographers, editors, and publishers have done a lot of work—from selecting cropping, captioning, and even Photoshopping an image— to shape what we see. All we can do, Morris suggests, is be aware that a photograph alone does not tell us the whole story of its reality.

Morris is a lively guide through thorny ethical and moral terrain, and takes pains to engage his readers in the process. He transcribes conversations with his sources, so that readers can unravel these photographic mysteries as he does. These transcripts are reminiscent of the “interview chamber” technique Morris uses in films like The Fog of War, in which we occasionally hear Morris interrupt Robert McNamara’s monologue to get him back on track; an effort to belie the artifice of documentary filmmaking. McNamara, in fact, seems to have given Morris the thesis of this book. In the middle of “The Fog of War,” the former Secretary of Defense reflects on the US decision to get involved in the Vietnam War: “We were wrong. We had in our minds that mindset. And it carried such heavy costs. We see only half the story at times.” Morris chimes in: “We see only half the story at times we see what we want to believe,” “You’re absolutely right,” says McNamara. “Belief and seeing, they’re both often wrong.”

Morris was a private detective before he starting making films, and his talent for sleuthing makes his analysis and conclusions more convincing than, say, Sontag’s judgment of Fenton. In Morris’s latest interrogation of reality, he raises usually unasked questions and presents an airtight case: Like the witnesses, lawyers, and war-makers he’s unmasked before, photographs are not, in fact, telling the whole truth.

Lauren Elkin is a Paris-based writer and critic.