Mark Polizzotti

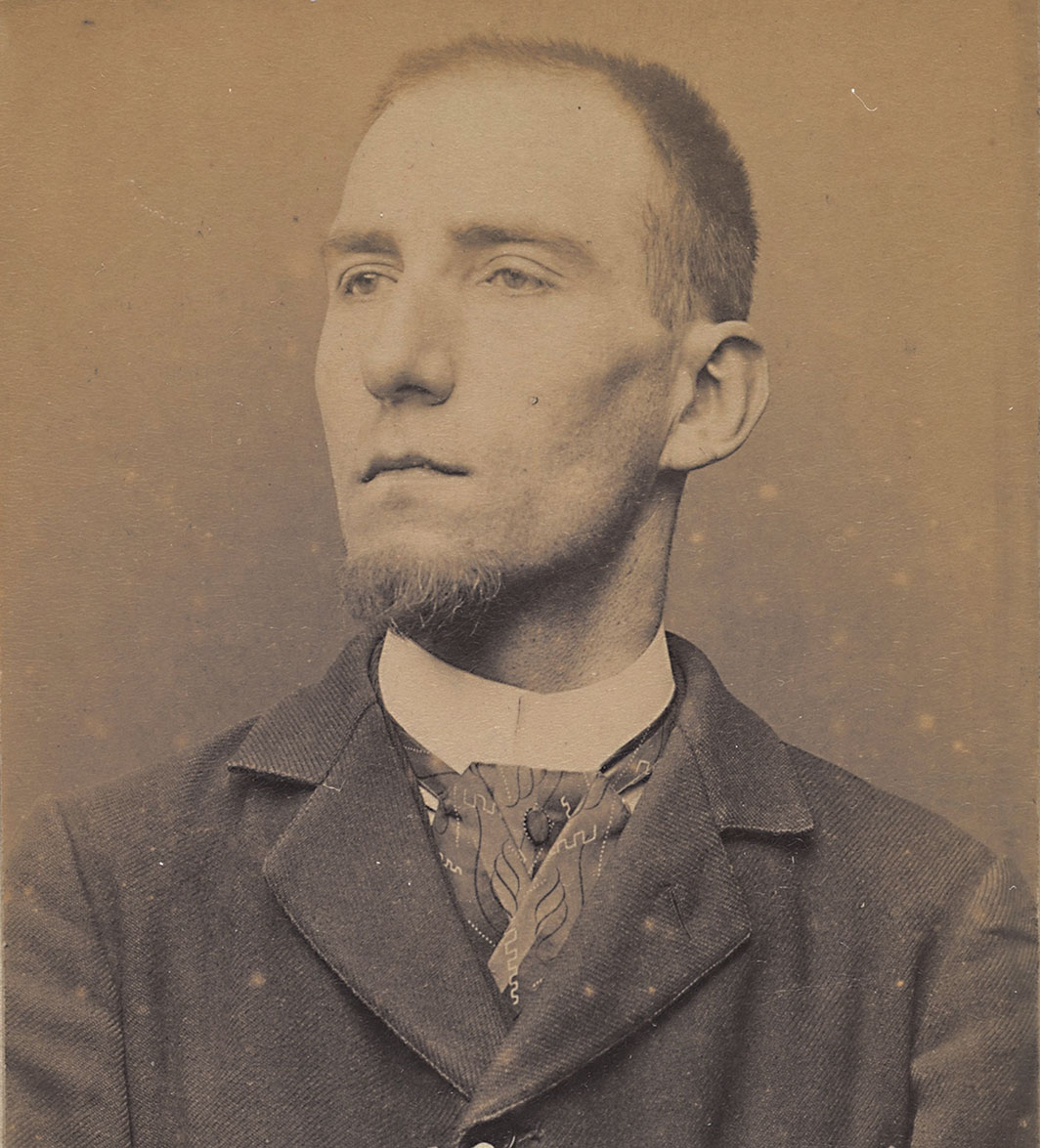

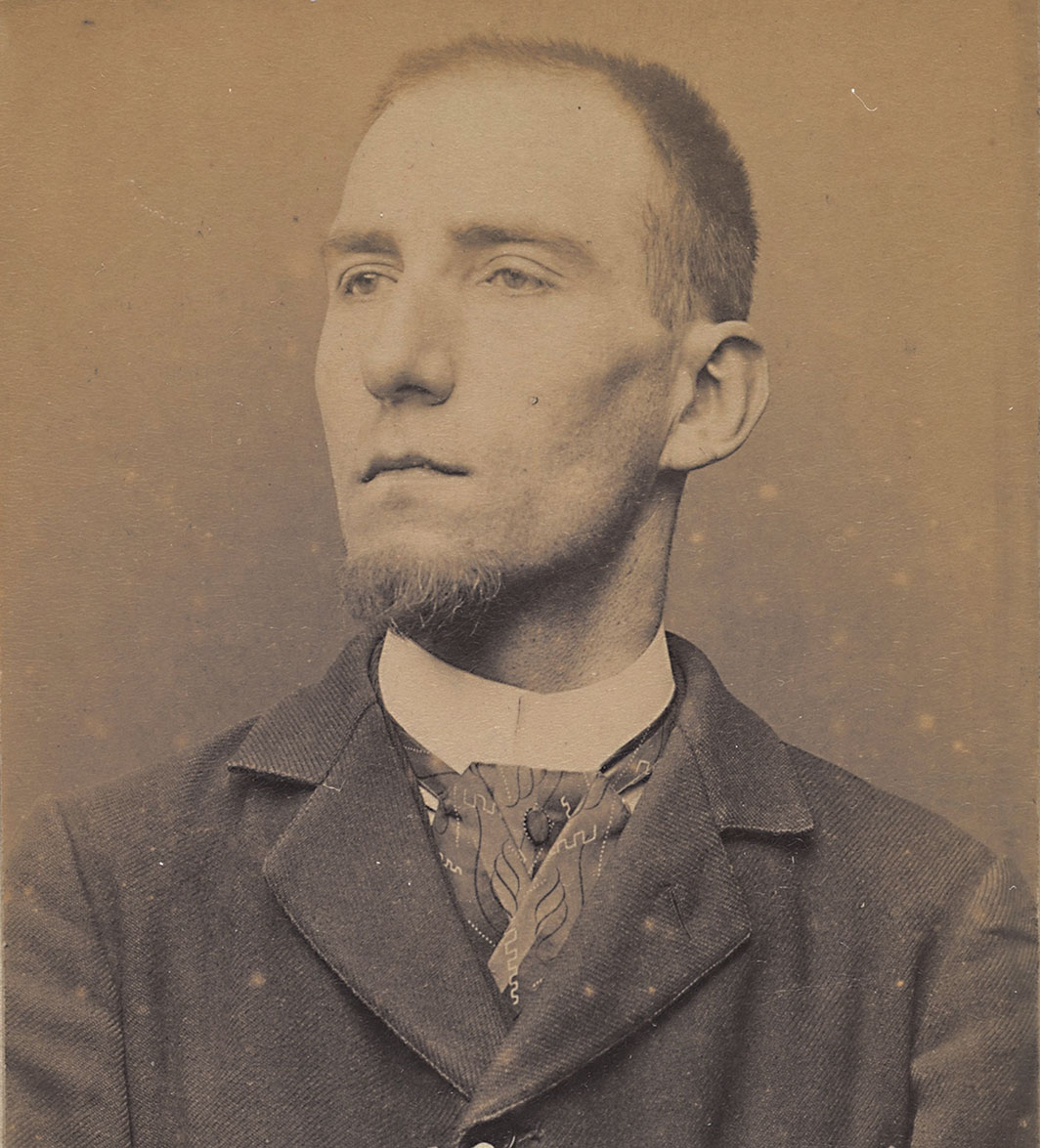

Two portraits of Félix Fénéon bookend his wide-ranging life and deeds. One, a highly stylized canvas by Paul Signac (1890) of the man as art critic, shows a “decorative Félix,” in gangly, goateed profile, proffering a lily against a background of swirling psychedelic colors. The other, a mug shot taken four years later, captures him as a prime suspect in a restaurant bombing. These twin personas, the aesthete and the activist, conspired to produce one of the truly unusual personalities of the French fin de siècle. Some sixty-five years after Dada first shook the stage, David Byrne debuted his own dadaistic twist on the limits of cognition: “Facts are simple and facts are straight . . . facts don’t do what I want them to.” One place where facts often don’t do what one wants them to is in a biography, where the simple narration of events is not enough to bring a subject to life—where, as Byrne says, “facts are living turned inside out,” from palpitating existence to dry recital. To a large extent, that is the problem with TaTa DaDa, Marius Hentea’s biography of

Some years ago, while I was interviewing a cordial octogenarian for my biography of André Breton—often called, to his disgust, the “Pope of Surrealism”—my interviewee suddenly leaned across the table and threatened to give me “a sound thrashing” if I used the abhorred word pope in my book. I did include the term, of course, but not without trepidation—a fear that had little to do with the outrage of vengeful codgers and everything to do with disappointing those whose trust I’d spent years courting. It’s a quandary for any biographer, particularly when writing about a figure who still inflames the