Some years ago, while I was interviewing a cordial octogenarian for my biography of André Breton—often called, to his disgust, the “Pope of Surrealism”—my interviewee suddenly leaned across the table and threatened to give me “a sound thrashing” if I used the abhorred word pope in my book. I did include the term, of course, but not without trepidation—a fear that had little to do with the outrage of vengeful codgers and everything to do with disappointing those whose trust I’d spent years courting. It’s a quandary for any biographer, particularly when writing about a figure who still inflames the passions of a fervent cult: Does one respect the insider’s code and eschew those aspects of the subject deemed vulgar, indiscreet, or commonplace? Or does one acknowledge that, for the general reader, such inconvenient or well-rehearsed truths are an integral part of the story?

In some ways, Alfred Jarry is the poster boy for literary cult figures. Like fellow turn-of-the-century French eccentrics Arthur Cravan, Raymond Roussel, and Jacques Vaché—though more famous than any of them—Jarry has left a legacy based partly on an enigmatic, often hermetic body of writing, and partly on an equally enigmatic, and more flamboyant, garland of anecdotes. Figures as diverse as Apollinaire, Picasso (with whom Jarry might have had a dalliance), the Surrealists, Italo Calvino, Philip K. Dick, J. G. Ballard, and even Sir Paul of Liverpool have acknowledged his influence—one that owed as much to Jarry’s nonconformist attitude as it did to his writing. The literary historian Roger Shattuck enshrined Jarry as one of the four great French precursors to modernism (along with Erik Satie, Apollinaire, and Henri Rousseau) in his magisterial 1958 study, The Banquet Years; in France, Jarry’s works fill three volumes of the Pléiade—the ultimate literary canonization.

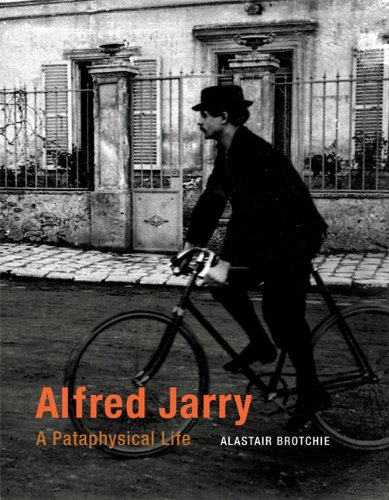

The irony is that Jarry’s eminent status rests mainly on the play Ubu Roi, an extended schoolboy farce, largely cribbed from former classmates, that reads like Macbeth rewritten by W. C. Fields and directed by the makers of South Park. The play, which premiered to a huge uproar in December 1896, both secured Jarry’s fame and sealed his fate at the age of twenty-three. As Alastair Brotchie points out in his absorbing but imperfect volume (the first full-length biography in English), Ubu Roi also helped turn its young author from a literary aspirant into a curiosity, perhaps known more for the stories told about him than for the ones he composed.

Alfred-Henri Jarry was born in Laval, France, in 1873, the child of a lackluster union between Caroline, a “whimsical, not to say erratic” mother, and Anselme, the indolent co-owner of a textile manufacturing business. When Alfred was almost six, Caroline deserted her husband and took their children to Brittany, the first of several relocations over the coming years. Brotchie maintains that young Alfred felt only “indifference” toward his father while retaining a lifelong affection for maman, but the dichotomy was perhaps not so clear-cut: Shattuck, for one, convincingly argues that Jarry, the “sensible maniac,” inherited traits from both parents.

In his teens, Jarry was already displaying the irreverent wit, pugnacious humor, and colorfully crude language that would later make his rep. One schoolmate recalled that the young Jarry “delighted in attacks on our modesty. He loved to see our cheeks redden with shame and envy.” The most notable of Jarry’s targets was his physics teacher, a pompous, reactionary incompetent named Félix-Frédéric Hébert, who for years had been the butt of his students’ satires under the nicknames “Père Hébé” or “P.H.” Well before Jarry transformed Père Hébé into Père Ubu, adding his own dashes of comic genius, the character’s main attributes were firmly in place.

Jarry’s Ubu, as Brotchie writes, is an “unrestrained and tempestuous being . . . bent only on pitiless self-gratification and revenge,” “a personification of some of the less comforting aspects of the human condition.” The bastard spawn of Rabelaisian excess, slapstick, schoolboy humor, and infantile regression, Ubu blusters and butchers his way through the play’s five acts, dispatching both friend and foe “down the hatch” for “torture, twisting of the neck, extrusion of the nearoles, and disembraining,” and despoiling his subjects with such neologistic weaponry as the “phynance-hook” and the “pschittasword.” As repulsive as Ubu is, something undeniably seductive emerges from this display of pure id, especially when expressed in such comically grotesque patois and delivered in an exaggeratedly precise, staccato monotone that became Ubu’s signature—as well as Jarry’s. Nor was it only Jarry who succumbed to his antihero’s dubious attractions; before long, Ubu-speak became a fad.

The Ubu plays—like any good franchise, this one bore sequels—were not Jarry’s only works. Brotchie calls Jarry a “writing machine,” made up of unequal parts classical culture, fanatical cycling, and devout alcohol abuse. The man who did everything to excess, including writing (and writing about excess), churned out a notable quantity of novels, plays, puppet shows, poems, adaptations, essays, theater criticism, and opinion pieces. He also penned the unclassifiable, posthumously published Exploits and Opinions of Doctor Faustroll, Pataphysician, Jarry’s fullest exploration of what he termed “pataphysics,” or the “science of imaginary solutions.” But none of these works exerted the same influence as Ubu Roi, whether on Jarry’s contemporaries, succeeding generations, or the author himself.

Stories abound of the shy, effeminate young man adopting the over-the-top behavior of his obstreperous brainchild. One of the most famous anecdotes recounts how Jarry, who carried a loaded revolver, shot at champagne bottles on a neighbor’s wall for target practice; when the neighbor rushed over to protest the threat to her children’s safety, Jarry unflappably replied, “Should that occur, Ma-da-me, we shall be pleased to make you some more.” Indeed, Jarry became so identified with Ubu that he found himself a virtual prisoner of his own creation: Brotchie tells of a luncheon hostess who, shocked by her celebrated guest’s good manners, prodded him until he let loose with the expected vulgarities—not that he needed much prodding, such as when he loudly volunteered at a posh soiree that he “had the squits” (that hostess did not invite him back).

That such tales—and this biography contains many, often quite humorous—threaten to overwhelm the man behind them is no accident. Since adolescence, Jarry had been a master entertainer, able to charm or offend any audience. By creating his outsize alter ego, first onstage, then in life, and letting it gradually subsume his entire person, he made it possible to get away with virtually any self-indulgence. Even his friends, whose affections were often strained by Jarry’s fecklessness and irresponsibility, could not escape the orbit of his persona. The magazine editor Alfred Vallette, who with his wife, the novelist Rachilde, was perhaps Jarry’s closest friend, summed him up as “charming, insupportable, and delightful.” Playing Ubu full-time was Jarry’s ultimate defense against the codes of a world he didn’t care to endorse, and it served him as well as anything until excesses of drink, squalid living, and poor health finally did him in at the age of thirty-four.

The consequence of such an all-consuming masquerade is that it is tricky to peel away the concealing layers. Alfred Jarry convincingly describes a man who orchestrated his own elusiveness, but for that very reason the portrait remains fragmentary and diffuse. To be fair, Brotchie is aware of the difficulties, and he occasionally breaks the fourth wall to tell us so: “The more settled Jarry became . . .the more disjointed his biography becomes.” Adding to the self-referential quality of the volume, every second chapter steps outside chronology to concentrate on a theme—pataphysics, misogyny, the debate over Ubu’s invention—interrupting the narrative flow.

Alfred Jarry’s attention to its own process is not surprising. Brotchie loves books (as founder of Atlas Press in London, he has published many authors influenced by Jarry), and reading his detailed descriptions of various early editions, one can sense his bibliophilic passion. He also punctuates his prose with enough nicely turned phrases to keep one reading, despite the occasional lapses into minutiae. But he is not a natural storyteller, and often can’t pluck out the trenchant detail that reveals more than a paragraph could—the pithy encapsulation at which The Banquet Years excels.

There are a few criticisms one could level at this biography, such as its equivocal stance toward women (almost invariably portrayed as ninnies or shrews, apart from Rachilde), or its inability to illuminate Jarry’s ambiguous love life. But its main flaw is its ambivalent tone, a swing between overdetailed exposition and colloquium-paper abstruseness. Perhaps Brotchie couldn’t decide which audience to serve: The scholars for whom the basic background and lively anecdotes are old hat, or the uninitiated for whom this book might act as an introduction to Jarry, amplifying and furthering the kind of revelation that The Banquet Years generated half a century ago.

This is a dilemma that most biographers face, but with Jarry it is even more pronounced. Few writers have woven published work and public persona into such a seamless carapace. And few are so in need of an intelligent, investigative probe into the life behind the scenes: Jarry at home, once the posturing has stopped and the absinthe high has worn off. Alfred Jarry provides many new facts, some pertinent analyses, and a clutch of outrageously amusing yarns. It’s as good a biography as we’re liable to get in English for some time. But it suffers from the same weakness as most portraits of Jarry, offering the usual chiaroscuro of insight and obscurity, never really seeming to, or allowing us to, know its subject—at least, no more than Jarry, stage manager of his own life and legend, allowed.

Mark Polizzotti is publisher and editor in chief at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the author of Revolution of the Mind: The Life of André Breton (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1995).