Minna Proctor

One night in Naples a number of years ago, the mother of an old friend who’d recently expatriated herself to southern Italy from Florence invited us over for a small dinner party. A worldly and glamorous figure under normal circumstances, that night she had her arm in a sling and apologized repeatedly for her cooking handicap. She pressed us giddily on our visit to Naples: the mysterious city built in layers on a dramatically swooping volcanic landscape, filled with bridal shops and treasures of Western civilization neglected in dusty museums, yet seething with hidden, menacing systems of power. Had we

Several years ago (five, to be exact—my youngest had just taken her first steps) I became obsessed with questions of mothers and literature. I wanted a full accounting: mothers who wrote literature (and the logistics), literature about mothers and motherhood—not just books with mothers but books in which mothering is the point. I was particularly interested in archetypes of mothers in fiction, in whether there were any dramatic structures inherent to motherhood that could make or had made great complex stories. My questions were entirely self-interested. I wanted to find the trajectory from my purse full of baby wipes and

Given the thousands of pages that James Ellroy has published, the seven books that precede Perfidia in this super-series about the Los Angeles underworld, and the many critics who’ve chimed in over the years, a review of Ellroy’s new book, the longest one yet, the one that starts tugging the previous ones into a giant overarching narrative, is a thankless task. Ellroy is a cult. For many, he’s a you’re-in-or-you’re-out cult, because he’s intense and absolute and violent in every respect—emotionally, linguistically, and physically. He’s a brash writer who spins marvelously complicated, suspenseful plots. He is fluent in local period

In How Literature Saved My Life, David Shields argues for a pastiche, or collage form, in the personal essay. The logic is that a personal essay represents real life, which occurs in bits, pieces, interruptions, associations, contingencies, and the best-laid plans—and so the writing about real life should represent the battle between chaos and order. If that’s a fair argument, then how does it apply to the fiction of pastiche? Fiction is not answerable to real life, and so what is the point, exactly, of mirroring life’s chaos?

David Shields was a stutterer, an athlete, and he’s dying (we all are). Over the course of thirteen books he’s consistently and convincingly illustrated how those qualities make him the writer he is: concise, fearless, and urgent. More: Shields is a soulful writer, a skillful storyteller, and a man on the hunt for the Exquisite—something that can only be broadly described yet also includes deep nuances and exceptions. Shields is also, in a writerly sense, as brave as they come. He plunges, asserts, performs, stands off, and pushes forward. Art is categorical for David Shields: a “pathology lab, landfill, recycling

Thirteen years ago I wrote about Intimacy, Hanif Kureishi’s gritty divorce novel/memoir, and gratuitously (certainly a little too vigorously) contrasted it to the other popular divorce memoir on the shelves then, Breakup by Catherine Texier. Kureishi’s book was raw, impeccable, fearless. Texier’s book was a catharsis, uncouth, a cry of pain. Now that I have some divorce of my own under my belt, I have a clearer understanding of the divergent approaches. Divorce—or rather its particular combination of grief, agony, fear, and shame—is word chaos. It hurls writers back into the primordial ooze. Some writers freeze up. Other writers gush,

Butterflies flapping, according to students of chaos theory, can start typhoons. Carbon emissions make New York a city where tornadoes touch down. Social networking starts (or doesn’t start) political revolutions. Where does literature fit into all of that? Are its effects fleeting, important, transcendent, or trivial? What could possibly be the point of some well-built sentences that flower in the imagination, perhaps ignite a dinner conversation, and then fade with the next cell-phone bill, sinus infection, or rescheduled dentist appointment? After all, as Muriel Spark’s doppelgänger in Loitering with Intent explains about one of her literary creations, he “never existed,

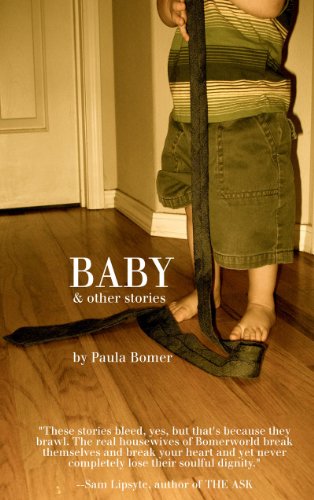

There’s a canny pageant of revelations on parade in Paula Bomer’s wry, butch, and persistently despairing debut collection, Baby & Other Stories. Not the kind of classic revelations that come at the end of most short stories, like the sun cracking open a rainy sky. Rather, these are more like broken umbrellas in a storm. The everyman misanthropes at the center of Bomer’s stories are subject to frequent, blunt epiphanies that uncover an axis of disappointment—with life, love, and procreation. Here is the dawning of truth: “In reality . . . the only real limit to one’s collection of behaviors They say that if you dream of being inside a house, you are dreaming about the landscape of your own mind. Upstairs, downstairs, long corridors, vast foyers, dark passages, and mysteriously locked doors. Indulge this association: A desk, too, could haunt a writer’s dreams. Massive yet rickety, loaded down with little drawers, one of which is locked with a missing key. Overlap a desk with a house—the task of a scribe, the container of a spirit—and the imagery veers into the religious. (Moses inscribing the Commandments, Saint Jerome translating the ancient texts, Rabbi Hillel conceiving of the Talmud.) At least