One night in Naples a number of years ago, the mother of an old friend who’d recently expatriated herself to southern Italy from Florence invited us over for a small dinner party. A worldly and glamorous figure under normal circumstances, that night she had her arm in a sling and apologized repeatedly for her cooking handicap. She pressed us giddily on our visit to Naples: the mysterious city built in layers on a dramatically swooping volcanic landscape, filled with bridal shops and treasures of Western civilization neglected in dusty museums, yet seething with hidden, menacing systems of power. Had we seen this garden, that castle, eaten ricotta pastries from this bar in the Vomero? Did we like it? Did we understand? She joked about having her arm in a sling: It was romantic, she thought. It made her feel like a real Neapolitan lady. The Neapolitans are so passionate, she said. “They’re always giving each other black eyes and fat lips in the throes of passion. You look closely tomorrow. When you go sightseeing on Corso Umberto I. All of the handsome young people. Everyone has bruises and they’ve all gotten laid.”

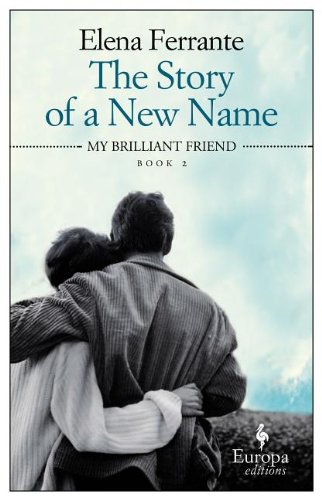

I wasn’t able the next day to confidently identify lovers’ bruises, but I did start to understand the volatility and the sheer, almost oppressive otherness of Naples. Naples is a city (speaking broadly) that hates itself . . . as a point of honor. Its streets are infected with poverty and corruption and fertilized by local mores. Civic pride seems to swell around how vertiginously a taxi driver can swindle a tourist. Gorgeous sloping avenues with sublime views of the bay are filthy with graffiti, broken glass, and urine. If Naples were a person, she’d be a gorgeous, moonfaced teenager who self-mutilates and scowls angrily at her loved ones because she is lonely. If this vexing city had a bard—many stake the claim—it would be Elena Ferrante, the secretive novelist who captures the violence, vulnerability, defensiveness, and seductions of the city with skin-prickling candor. Her latest book, The Story of a New Name, a portrait of two girls coming of age in 1960s Naples, takes on the teenager herself.

Ferrante writes about Naples and its hermetic culture from the keenly detailed perspective of someone who disdains her subject, and yet can’t pull herself away from it. All of Ferrante’s difficult, brassy, exotically intelligent heroines—from her 1991 debut, L’amore molesto (Troubling Love), to her latest—have fled, are fleeing, or dream of fleeing the slum they were born into and everything that it represents. Even The Days of Abandonment, set entirely in Turin, is haunted by the specter of the heroine’s childhood in Naples, where women are bred to serve their men, and be worthless without them.

The Story of a New Name—the second book, after My Brilliant Friend, of Ferrante’s Neapolitan trilogy—is an epic about two childhood friends getting out from under their garish birthright. “We had seen our fathers beat our mothers from childhood. We had grown up thinking that a stranger must not even touch us, but that our father, our boyfriend, and our husband could hit us when they liked, out of love, to educate us, to reeducate us.” This volume of the saga portrays the girls on the threshold of adulthood. They are sixteen, one married and one in high school—too smart not to see the hint of something better than their circumstances, and too young to know how to pursue it. This friendship is the locus of all the dramatic, flailing missteps of young women everywhere, the passions, the delusions, the recklessness. No matter how distant and essentially exotic Ferrante’s Naples, the unadulterated naturalistic psychology of her characters cuts very close to the bone. There are few writers who so acutely and seductively frame the eternally wounded, stupidly brave teenager inside a grown woman’s heart.

[[img]]

The Story of a New Name begins in 1960 at the same wedding where My Brilliant Friend ended. Halfway through the reception, the bride, Lila Cerullo, realizes that her husband has given away to the neighborhood loan shark a pair of shoes that Lila, a cobbler’s daughter, spent months designing, a pair of shoes that she had “ruined her hands” to make. It is a subtle and poisonous revelation—the minor gesture that will define the doomed marriage. From this moment, which bridges the two novels and marks the end of “childhood” and the beginning of “adolescence,” The Story of a New Name is predominantly about the impact of that marriage. How becoming Signora Carracci changes Lila’s destiny, and how it separates Lila from her soul mate and foil, Elena.

Elena is the narrator of the trilogy and presumably the author’s avatar. In an environment where families can’t afford to send their children to school past eighth grade and where girls get married at sixteen, she is an awkward, scholarly girl in bad glasses and old felt dresses who somehow talked her parents into letting her get educated. Elena has to rely on the patronage of her professors in order to borrow the books she needs for school. She speaks Italian rather than coarse dialect when she wants to win an argument. Her people are at once proud of her and resent her superior airs and aspirations. And still, in her mind (because everything that isn’t skin-on-skin in Ferrante happens in the whirling unquiet mind), Elena plays second fiddle to Lila—who is ferocious, resourceful, independent, beautiful, and brilliant. Though with all of that, Lila’s parents won’t send her to school. Instead, Lila gets married and begins to learn how to cultivate power through capitulation. The capitulation, we soon learn, starts on her wedding night, when her groom beats and rapes her.

The two girls pull apart after the wedding and then come together again, following a practically pathological pattern of friendship:

But when I saw her so battered, my heart leaped to my throat, I embraced her. And when she said she hadn’t come to visit because she didn’t want me to see her in that state, tears came to my eyes. The story of her honeymoon . . . made me angry, pained me. And yet, I have to admit, I also felt a tenuous pleasure. I was content to discover that Lila now needed help, maybe protection, and that admission of fragility not toward the neighborhood but toward me moved me.

The currency of fragility and dependence drives their difficult dynamic. Lila is trapped but rich, and tries to subsidize, even control, Elena’s schooling. Elena has extended herself beyond her crude childhood neighborhood. She is liberated—and, from Lila’s perspective, dignified, already “improved.” But in fact Elena has no models for who she wants to be, which means she’s making things up as she goes along, following her own set of cardboard rules. That leaves her gullible and passive and cagey. She can’t admit to her boyfriend that she doesn’t want to marry him and help him run a gas station, so she breaks his spirit instead. She can’t admit to anyone her long, tortured crush on Nino Serratore—a fellow student from the neighborhood—so she contrives to be near him and stealthily win his heart. The plot goes horribly wrong when she convinces Lila to take her on summer vacation near him, and continuing to insist she has no feelings for the boy, watches instead, helplessly, as he and Lila fall madly in love.

There’s an unforgiving cruelty to the world that Ferrante releases her characters into. They are molested and beaten, but then transported by a crush. They’re never given any reason to look at love and sex as anything other than mercenary, and yet they let themselves desire. Lila and Elena vacillate between numbness and fever—falling victim to both. “I didn’t feel the urgency, which I read in Lila’s eyes, in her half-closed mouth, in her clenched fists, to go back, to be reunited with the person I had had to leave. And if on the surface my condition might seem more solid, more compact, here instead, beside Lila, I felt sodden, earth too soaked with water.” Often the two girls hold each other accountable for matters far outside their control, if only because deep down they have no one else. The cost of escape is isolation.

Ever since I started reading Elena Ferrante fifteen years ago, after being completely mystified and seduced by Mario Martone’s film adaptation of L’amore molesto, much has been made of her secret identity: a writer who doesn’t appear in public, who only gives interviews by mail or e-mail, who may or may not live in Italy (or is it Greece?), who may or may not be a man—specifically the marvelous Neapolitan novelist Domenico Starnone—is probably divorced, is probably a mother, and was definitely, certainly born in Naples. Her anonymity has over the years seemed an important part of her artistic vision, possibly a way of protecting the identities of real people that her characters are based on, and a kind of political literary posture: “I believe that books, once they are written,” she writes in a published letter to her Italian editor, “have no need of their authors. If they have something to say, they will sooner or later find readers; if not, they won’t.” Which is pure and idealist, arguably disingenuous, and, I’ve come to believe these many years later, really beside the point. Ferrante is an exceptional writer because of the raw integrity of her characters’ emotional psychology. Her books bleed on you, implicate you, make you uncomfortable, draw you into the compromises, regrets, and masochism of daily life. “When one writes, one must never lie,” she explains. “In literary fiction you have to be sincere to the point where it’s unbearable.” Who cares what color her hair is, or if she still smokes? Ferrante is entirely exposed.

It’s difficult to describe what it’s like to be inside a Ferrante book, precisely because it doesn’t feel like “being in a book.” It’s quite a bit more like being in a life. Ferrante’s writing is so unencumbered, so natural, and yet so lovely, brazen, and flush. The constancy of detail and the pacing that zips and skips then slows to a real-time crawl have an almost psychic effect, bringing you deeply into synchronicity with the discomforts and urgency of the characters’ emotions. Ferrante is unlike other writers—not because she’s innovative, but rather because she’s unselfconscious and brutally, diligently honest.

Minna Proctor is the editor of the Literary Review.