Nathan Lee

Among the course offerings announced by the University of Michigan in the fall of 2000 was an undergraduate English seminar titled “How to Be Gay.” Led by professor David M. Halperin, a well-known figure in queer studies, the class proposed to examine the Lavender Canon in all its mincing flamboyance: Judy and Liza, opera and Broadway, divas and drag, muscle queens and Mommie Dearest. “Are there,” Halperin asked, “a number of classically ‘gay’ works such that, despite changing tastes and generations, ALL gay men, of whatever class, race, or ethnicity, need to know them, in order to be gay?” Oooh

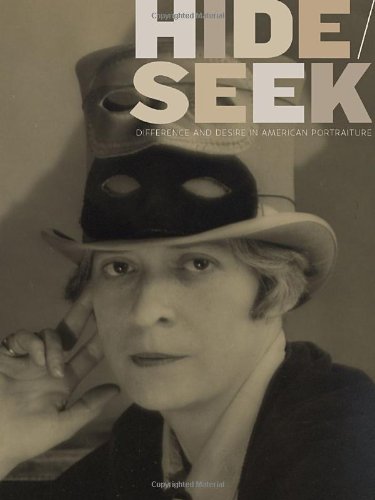

By yanking David Wojnarowicz’s film A Fire in My Belly (1986–87) from the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition “Hide/Seek,” Smithsonian secretary G. Wayne Clough gifted to art history a splendid case study in cowardice, censorship, and institutional failure. Far from undermining the exhibition (which closed last February), moreover, Clough’s capitulation to the grumblings of the Catholic League managed to validate beyond all expectations the relevance of the show’s conceit. The Wojnarowicz Affair performed the very premise advanced by curators Jonathan Katz and David C. Ward: a story of queer portraiture told through a dialectical account of absence/presence, shame/pride, closeted/out, hidden/revealed. The publication of two monographs devoted to the art of David Lynch—paintings, photographs, works on paper, installations, canvases smeared with animal corpses—suggests a new way to think about an artist too often taken for an architect of dreamscapes, a fabulist of the psychosexual bizarre. The opposite is just as true: Lynch as a supremely earthly, material artist, whose great subject is the human body in all its banality—and strangeness. The most “Lynchian” of Lynch’s films are intensely corporeal: Eraserhead (1977), with its reproductive phantasmagoria; the exposed and dismantled bodies of Blue Velvet (1986); Twin Peaks (1990–91), a melodramatic labyrinth with “Spare me smart Jewish girls with their typewriters,” quipped Clement Greenberg, the legendary critic of modernism, to Rosalind Krauss, his most brilliant disciple. It was 1974: Krauss had made a name for herself writing on Minimalism in the pages of Artforum but would soon leave the magazine to cofound October. As promised by the journal’s name, a revolution in art history was afoot.