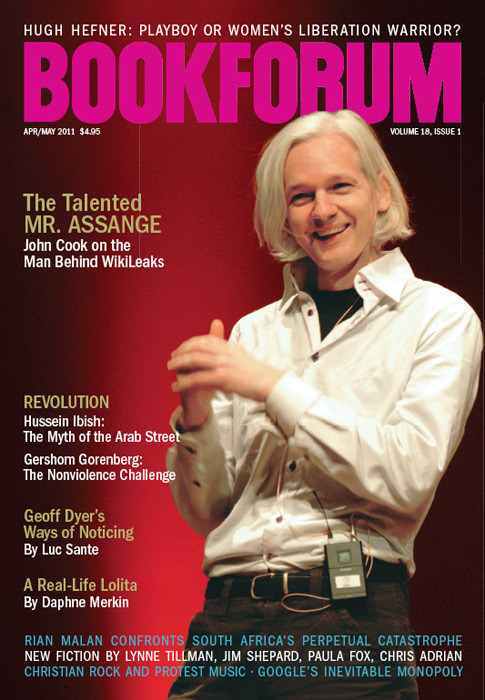

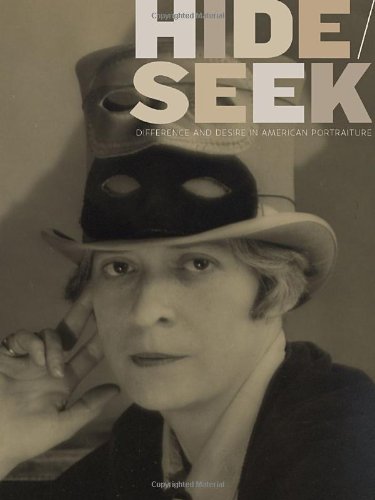

By yanking David Wojnarowicz’s film A Fire in My Belly (1986–87) from the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition “Hide/Seek,” Smithsonian secretary G. Wayne Clough gifted to art history a splendid case study in cowardice, censorship, and institutional failure. Far from undermining the exhibition (which closed last February), moreover, Clough’s capitulation to the grumblings of the Catholic League managed to validate beyond all expectations the relevance of the show’s conceit. The Wojnarowicz Affair performed the very premise advanced by curators Jonathan Katz and David C. Ward: a story of queer portraiture told through a dialectical account of absence/presence, shame/pride, closeted/out, hidden/revealed.

“Hide/Seek” was marked by elisions from its inception. The title itself points to a work missing from the show, Pavel Tchelitchew’s great 1940–42 canvas Hide-and-Seek. Anchored by the central figure of a gnarled tree that doubles as a hybrid hand-foot appendage and organized as an elaborate vortex of visual puns conflating anatomy, biology, botany, and the cycle of seasons, this peerlessly seductive painting was, as Katz notes in his introductory essay to the catalogue, once the most popular painting in the Museum of Modern Art. An openly gay representational painter, Tchelitchew fell out of favor during the ascendancy of Abstract Expressionism, and it was just recently that his masterwork was returned to view at MoMA after decades in storage.

Katz understands the multivalent strategies of Tchelitchew’s painting as “familiar to a subculture long used to employing protective camouflage, while at the same time searching for tiny signs, clues, or signals that might reveal the presence of other queer people.” Indeed, queer people must read between the lines of the show’s blandly abstract subtitle, “Difference and Desire in American Portraiture,” to recognize a project about their own experience—albeit one that deploys portraiture to interrogate what it means to identify with the contemporary categories LGBT or Q.

[[img]]

Well, not so much T. From Marcel Duchamp to Catherine Opie, “Hide/Seek” offers a generous perspective on the aesthetic of drag but has little to say about explicitly transgendered history, experience, or representation. As might be expected of a show at the nation’s official portrait gallery, “Hide/Seek” is very much a canonical project—a straight show about queer art. Katz and Ward are up-front about the exclusionary scope of difference they’re going to address. “Our goal,” writes Katz, “is not to challenge the register of great American artists, but rather to underscore how sexuality informed their practice in the ways we routinely accept for straight artists. . . . While we have tried to represent a diverse group of artists, our emphasis on canonical figures has worked against our desire for inclusivity.” We should be thankful, I suppose, for such frank laying of the curatorial cards on the table. Acknowledging that one will be predictable does not, however, make for a less predictable exhibition.

“Hide/Seek” does not much recall—or bother to mention—”In a Different Light,” the last major survey of queer art in America, curated by Nayland Blake and Lawrence Rinder at the Berkeley Art Museum in 1995, but rather summons another handsome, middlebrow production whose importance lay precisely in using a stable, canonical form as the vehicle for novel queer affect: Brokeback Mountain. “Hide/Seek” begins its story of difference and desire in a world of erotic indeterminacy that Jack and Ennis would have felt at home in. Thomas Eakins’s Salutat (1898), a splendid (and to contemporary eyes blatantly homoerotic) portrait of a bootylicious young boxer, offers a richly ambiguous starting point for the curators’ historicization. How, Katz asks, “can we discuss Eakins’s sexuality in advance of the very words that convey it?”

Finding, naming, identifying, and describing positions within the matrix of (sexual) difference and (same-sex) desire: This is the project—and the problem—laid out by Katz and Ward. “Hide/Seek features straight artists representing gay figures, gay artists representing gay figures, and even straight artists representing straight figures (when of interest to gay people/culture).” The curious matter of what may be “of interest to gay people/culture” leads to some fuzzy justifications. Katz devotes several pages of his essay to parsing the “lesbian” vision of Georgia O’Keeffe, which amounts to reading her animal-skull paintings as representing “dry” vaginas rendered “illegible” to men. This is preferable, at least, to the boilerplate analysis of a Berenice Abbott photo as “tender[ing] an explicit resistance to colonization by the heterosexual male gaze.” If one is dismayed by the masculine bias, both in the quantity of works on view and in the quality of discourse in the catalogue, it is perhaps to be expected of a “male gaze” that finds it “takes much dedicated looking” to parse the quite obvious act of cunnilingus in Tee Corinne’s kaleidoscopic Yantra of Womanlove #41 (1982).

On more familiar turf, Katz productively scrutinizes Robert Rauschenberg’s pictures and Combines, decoding fragments of text persuasively read in light of his relationship with Jasper Johns. Though one may question Katz’s claim that their relationship “was doubtless the crucible of their artistic development, of their signature styles,” he poignantly draws attention to, for example, a scrap of comic-book dialogue in Rauschenberg’s Collection (1954), made shortly after meeting Johns: “How depressing life would be, if our lucky stars hadn’t introduced you to me.”

In one of his six essays scattered throughout the catalogue, Ward insightfully contextualizes this aesthetic of evasion and coding in light of cold-war paranoia and ideological witch hunts. The hide/seek interpretive framework peaks around the discussion of midcentury aesthetics—Rauschenberg, Johns, and the advent of a Zen-inflected avant-garde by artists like John Cage and Agnes Martin. Zen, Katz argues in relation to Martin’s grid paintings, enables a mode of strategic silence: “Paradoxically then, the evasion of sexual difference, inevitably sorrowful in the Western tradition, under Zen became its own palliative.”

And what to do when Silence = Death? Katz and Ward demonstrate how gay portraiture took on new subjects, strategies, and urgency during the AIDS crisis. Approaching his death from AIDS, Wojnarowicz shot a photographic memento mori of his face merging with the dust of the earth (Untitled, Face in Dirt, 1990). AA Bronson immortalized the skeletal corpse of his fallen partner, the artist Felix Partz, in an image of shattering force and compassion. Felix Gonzalez-Torres remembered his own fallen lover with “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) (1991), a pile of multicolored candies equivalent to Ross Laycock’s 175-pound body weight. Invited to help themselves to the plastic-wrapped sweets, audiences participate in the slow removal of the surrogate flesh, which is then replenished by the institution.

Gonzalez-Torres, notes Katz, can be seen as extending a genealogy of conceptual queer portraiture born with Duchamp and passing through Rauschenberg and Johns. Despite the power of these works, the curators start to fumble their narrative when attempting to contextualize the AIDS era within postmodernism. Proceeding from the preposterous notion that premodern painters merely “represented the world as it appeared to them” and reprising the outdated theory of modernism as a sustained, medium-centric critique devoted to the flattening of the pictorial surface (a story that Tchelitchew, for one, renders obsolete), Ward summarizes:

Hide/Seek has two conclusions, or more precisely, it has a coda that can only hazard a guess at the future. The problem is the appearance of the monstrous HIV/AIDS epidemic in the early 1980’s. Its metastasizing and ravaging of the gay population and other communities destroys the progressive narrative that would have transpired had the epidemic never occurred. Without AIDS, the arc of Hide/Seek would have been straightforward: the insistence of a binary definition of sexuality with the codification (indeed criminalization) of homosexuality led to decades in which gay and lesbian artists developed strategies (hiding and seeking, as it were) to work creatively and even to survive.

Notwithstanding its apparent contradiction of a previous statement by Katz (“one of the most conspicuous aspects of this book is its refusal to frame queer history as moving in one direction only, toward ever-growing tolerance and social acceptance”), this conclusion is curiously muddled. What, in Ward’s account, did AIDS bring an end to? Clearly not those strategies of creativity and survival marshaled in the work of Bronson, Gonzalez-Torres, and Wojnarowicz, to say nothing of other “Hide/Seek” artists like Robert Gober, Keith Haring, and Robert Mapplethorpe. It is true that these artists belonged to an era in which concepts like “progress” and “narrative” came in for critique, but to imply that AIDS somehow brought the project of queer agency and recognition to a screeching halt is to mistake suffering for regression, oppression for invisibility. AIDS produced as much as it destroyed; the tyranny of the disease went hand in hand with insurgencies in the fields of politics, discourse, and representation. Postmodernism, the art-historical period associated with the AIDS crisis, may well be an “exasperating term,” as Ward says, but you don’t have to be Fredric Jameson to grasp how it cultivates strategies of hiding and seeking with the utmost sophistication.

Ward’s belief that we are “still hamstrung by the age of AIDS, one in which the liberation promised by 1969 has only been imperfectly realized or actually retrogressed,” delineates not a claim but an imaginative and scholarly limit that fails to account for how the kind of art surveyed in “Hide/Seek” (urban, privileged, canonical) is now produced in a decidedly post-AIDS culture with an entirely different set of problems and practices. Catalogue entries on works by Anthony Goicolea, Cass Bird, and Glenn Ligon confirm aesthetics previously glossed rather than chart the currents of emerging queer art. There’s no reflection on performance or new-media work, no collectives or publications, no exploration of how anonymity and connectivity play out in the queer space of the Internet. Jack Pierson has far less to tell us about the evolution of queer portraiture than does any profile on manhunt.net.

Katz concludes with a utopian speculation on a polymorphous future unstructured by binaries of gay/straight, queer/trade, male/female, and, indeed, hide/seek. In time, he writes, “perhaps this book itself might be viewed as something akin to a survey expedition, a means of chronicling a species just prior to its disappearance.” An obsolescent project that dreams of obsolescence? Queer indeed.

Nathan Lee is a critic and curator based in New York.