Nicole Rudick

Dubravka Ugresic is Walter Benjamin’s Baudelaire, the poetic sojourner who finds himself at the whim of the crowd. She is the flaneur cast into the streets, nowhere at home. And like Baudelaire, Ugresic is a writer in full view of and at odds with the forces of commodity culture, a writer whose mission is to give form to modernity. But if Baudelaire’s poetry is permeated by melancholic doom, Ugresic’s diagnosis of life’s illusory qualities is delightfully judgmental and cheerily pessimistic. Or as she tartly concludes in Nobody’s Home, her new collection of essays, “this book breaks the rules of good

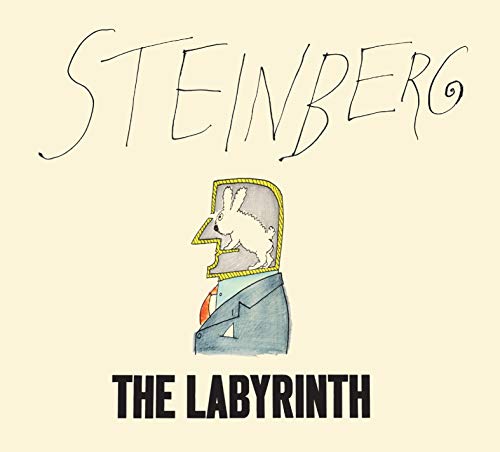

Saul Steinberg couldn’t fully enumerate the contents of The Labyrinth in words. For a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1978, he composed a list of the subjects explored in the book of drawings, originally published in 1960 and recently reissued by New York Review Comics. It begins with “illusion, talks, women, cats, dogs, birds, the cube” before trailing off, a dozen items later, with “geometry, heroes, harpies, etc.” The Bauhaus is coming to New York. A retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art later this fall will be accompanied by an immense catalogue, detailing a dazzling array of the school’s ideas and objects. But before the onslaught of Gropius, Klee, Kandinsky, Albers, Breuer, Moholy-Nagy, Itten, and Schlemmer, one ought to peruse this intimate volume of work and writings by Gunta Stölzl, the school’s only female master. Coeditor Monika Stadler (both editors are the artist’s daughters), in a nostalgic glance back at her childhood, calls the interwoven text and images a “picture book,” and the term is quite In 2006, Kehinde Wiley painted Le Roi à la Chasse, in which a T-shirted young black man imitates the pose assumed by Charles I in Anthony van Dyck’s 1635 canvas of the same name. Though Wiley’s model introduces a casualness into the king’s formal comportment by tossing back his head as if to saunter forward, it is the version of van Dyck’s pastoral portrait in Black Light—Wiley’s first foray into photography—that provides a strikingly contemporary interpretation. Here, the model gazes unswervingly out from the picture, catching us with his look and, through photography’s immediacy, holding us fast. The play of “O LORD, WHAT A VARIETY OF THINGS YOU HAVE MADE! In wisdom you have made them all.” We know He made the lamb and the tiger, but what about the yeti, the kraken, and the manticore? Not to mention the Invunche, a “twisted, deformed, pathetic creature” that started out as “an innocent Chilean boy who is sold to a warlock.” Then there’s the flesh-eating Burmese Khimakha, an ogre so hideous that he’s ugly “even by ogre standards.” Oh, and Mothman: It looks like a human, except that it has “massive wings, no head, and a set of large, reflective eyes As a retrospective of the work of Wassily Kandinsky makes its way from Munich to Paris to New York over the course of this year—roughly tracing the artist’s own westward path during his lifetime—fortunate viewers will experience one of the greatest concentrations of his art. Much as previous shows have presented piecemeal considerations of his body of work, so have publications tended toward examinations limited to certain media or particular periods. But to see the evolution of his painting is to witness the birth of a modernist master: early figurative canvases mixing French Impressionism and Fauvism with Russian folktales; the In a drawing of Texas in which the state is superimposed on a cross, Austin is designated by a pentagram sunk into a vortex. A dog’s head severed from a monstrous humanoid form inaccurately observes, “CROSS ON TEXAS,” and a trepanned human head with sunken eyes interjects, “DEATH TO SUICIDE.” Such is the landscape of Daniel Johnston’s drawings—cartoonish collisions of perspective whose Magic Marker palette extends from bright to brighter. But the more than eighty works that make up this monograph, the most comprehensive of his artwork to date, retain too much emotional presence to be mistaken for the doodles In historical photographs, events from long ago are easy to distinguish from more recent ones: The distant past is always in black-and-white. Even though experiments in color photography began in the mid-nineteenth century, color wouldn’t be widely used until the mid-1930s, and even then mainly for documentary and commercial purposes. But in 1909, two years after the Lumière brothers invented the Autochrome process, French banker and philanthropist Albert Kahn initiated a twenty-two-year project (brought to an end by his ruin in the Great Depression) to photograph the world in color. Known as the Archives de la Planète, this astounding body Gary Panter is a difficult artist to pin down. He’s a cartoonist, best known for his buzz-cut everyman, Jimbo. He performs light shows, makes puppets, constructs tiny cardboard architectural models, and writes and draws an animated Internet show. He’s done illustration work and album art. He’s even been a production designer, creating much of the surreal set for Pee-wee’s Playhouse (the job earned him three Emmy Awards), and an interior designer, for a children’s playroom in Philippe Starck’s Paramount Hotel in New York. But this two-volume monograph makes the case for his paintings.