Saul Steinberg couldn’t fully enumerate the contents of The Labyrinth in words. For a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1978, he composed a list of the subjects explored in the book of drawings, originally published in 1960 and recently reissued by New York Review Comics. It begins with “illusion, talks, women, cats, dogs, birds, the cube” before trailing off, a dozen items later, with “geometry, heroes, harpies, etc.”

The title, too, gave Steinberg some trouble. He took several trips by car and bus throughout the United States between 1954 and 1960, during which the book’s drawings were made. In 1958, he provided an illustration for the cover of his friend Robert Frank’s new photobook, Les Américains, and thought his own book might likewise offer a view of the country. He initially called it Steinberg’s America. But this half decade also found Steinberg reflecting on the unlikely path of his life, from Romanian refugee to American citizen to well-known artist, secure in his professional reputation. He determined to focus on his creative vision over commercial work, and the title The Labyrinth would better announce these personal concerns.

Admittedly, when the reader begins to absorb The Labyrinth’s numerous and diverse subjects, that et cetera starts to sound like a fitting aperçu. The more than three hundred wordless drawings include work related to Steinberg’s travels with the Milwaukee Braves in the Midwest, mural projects for the Tenth Triennial of Milan and the US pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, backdrops for Rossini’s opera Count Ory, visits to the paddocks at Aqueduct, a New Yorker assignment to the Soviet Union, and trips through the American South and West, the mid-Atlantic states, and Alaska. The book also reflects the life of the mind: allegorical observations of American society and politics, the artist’s relationship to the world, and the nature of art itself. For instance, Steinberg’s mixed feelings about his own fame—acclaim was a boon and a burden—appear in the form of several drawings depicting Winged Victory, laurel wreath in hand. She is here as an antagonist, pursuing her target like an avenging angel; a captive, leashed to her master like a dog; and an elusive figure atop a bicycle wheel (the bicycle and the umbrella were, for Steinberg, “two perfect things that we cannot make for ourselves”). Elsewhere, a cube rendered in thick, rough lines imagines a perfectly formed version of itself, its sides erect and clean—the ideal to which the dreamer aspires. The book’s final drawing contains thirteen diagrams, each consisting of a point A and a point B. The line that connects the two is in each instance unique—frenzied, zigzagging, mazelike, digressive, looping, direct, or nonexistent; each describes the pattern of a life, “from (birth) A to the end, B.”

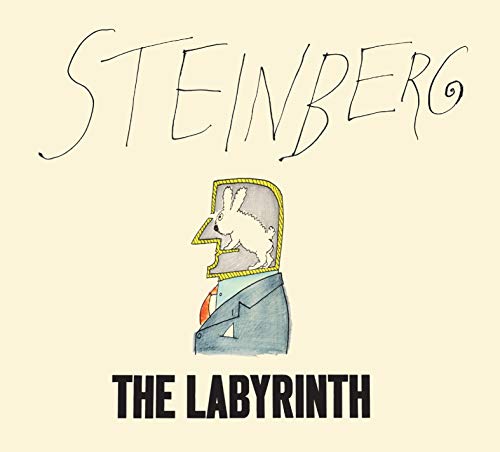

Steinberg thought of The Labyrinth as being autobio-graphical, and its dual perspectives—the outside world and the inner one—overlap. “The artist,” he wrote, “investigates all the other lives in order to understand the world and possibly himself before returning to his own.” The cover of the book shows the bust of a man drawn in profile. His tie is red, his suit is blue, and a peaked white handkerchief peers out of his breast pocket. Within the outline of his head resides a rabbit, who observes the world through the eyehole, like a tiny spy piloting a human-shaped exo-suit. Steinberg used this once-removed perspective to inform his social commentary. In a 1951 Life magazine profile of him and his wife, the artis Hedda Sterne, Steinberg admits to a fascination with the “habits of people” in the United States. Parades, for instance, gave him “an excuse to be staring at people,” ostensibly from behind his notebook. The Labyrinth itself proceeds like a parade: If it were published as an accordion fold, it would be a 226-foot strip of unbroken life. Reading it would be like walking down a paper boulevard, absorbing a kaleidoscope of architecture and people, situations and impressions.

The book’s first drawing illustrates this idea in miniature. It depicts the artist in the process of drawing a line that bisects the page horizontally. His pen—itself a short, straight stroke—intersects the long horizontal line, forming an obtuse angle that seems to tug both instrument and shape across the page. The line is a vector heading leftward as its long tail stretches to the right edge of the page and then continues, uninterrupted, across the next six pages, where it serves as the common denominator in a shifting panorama: as the horizon, the offing, a clothesline, a tabletop, a train track, a wall, a roof, a ceiling, a floor, a labyrinth. This multipage composition shows us that Steinberg’s line is protean, a descriptor of possibilities rather than facts, as Harold Rosenberg suggested (not unlike the boundless, versatile line in Crockett Johnson’s contempo-raneous Harold and the Purple Crayon). But more important, it shows that his line moves. Steinberg himself articulated this sense of peregrination when he proclaimed that “a line is a thought that went for a walk” (a famous quote that amends Paul Klee’s famous quote “a line is a dot that went for a walk”). Steinberg’s line, then, isn’t merely a means to an end, a way to build complex forms; it is observation in action and the visible progression of thought. It is a flâneur, a passionate spectator, to borrow from Baudelaire, constantly in motion in order to capture the pageantry of life and the artist’s attitude toward it. (It’s not for nothing that E. H. Gombrich deemed Steinberg the preeminent expert on “the philosophy of representation.”)

Back to The Labyrinth’s first drawing: Does the pen pull the line, or does the line move the pen? Drawings throughout the book are composed of lines with visible endpoints, and others that move circuitously in describing a figure or an object. But all appear to proceed without a definitive end, stretching on by way of that intrinsic vitality. If the line is thought in process, then the image that results from its perambulation is what Steinberg called a way of “reasoning on paper”; that is, language—and not a ready-made language, but an act of visual interpretation. Spoken language appears in a series of drawings early in the book: as florid ornament emitted from the speaker’s mouth like breath on a cold day, as an illegible and irascible block of text that imprisons the speaker, or as a solitary balloon adrift in the sky (à la The Red Balloon, which was released in 1956). Late in the book, words recur as objects with agency: The letters in tantrum self-combust, and the elegant serif letters in art perch precipitously atop one another to be studiously examined by uptown museumgoers.

The more extended series in the book include drawings from Steinberg’s American and Soviet sojourns, and both employ a great variety of linework. In the latter, he depicts a crowded street scene in brushy calligraphic marks before recording in fine detail the dress of inhabitants in Samarkand, differentiating, in a single drawing, six varieties of headwear. Back in the States, the dense crosshatching of the shady side of a rural Main Street makes a yin and yang with the bright white of the opposite side. By and large, however, these two travel portfolios are less searching, less thrillingly experimental than the book’s general mélange.

Steinberg may have approached these trips with more concrete aims, and perhaps with a frame already in mind. When he toured the mid-Atlantic and Southern states in 1958, he romanticized “the hillbillies, the poor whites.” “They are somewhat the ancestors of today’s Americans,” he told his friend Aldo Buzzi. “In them I saw many protagonists of American fiction, characters out of Faulkner, movie heroes, cowboys, thieves, tramps—the real American characters.” If his patronizing ideas about class were a shortcoming, race proved a more serious blind spot; only a handful of fi gures in The Labyrinth are nonwhite. The year after Eisenhower signed the Civil Rights Act of 1957 into law, Steinberg was commissioned to produce a mural for the American pavilion at the Brussels World’s Fair. (Four background drawings from the mural appear in The Labyrinth.) He was given the theme “The American Story,” within the pavilion’s larger theme of “A New Humanism,” but ran into a problem. “I’m in trouble,” he wrote to Buzzi. “How do you draw the blacks?” His solution was not to include any.

When The Labyrinth was published in 1960, its reception was mixed and it sold only about six thousand copies before going out of print, with some fifteen thousand copies unsold. Steinberg felt that reviewers “failed to grasp the essential quality,” reports his biographer Deirdre Bair. Even today, he is best known as a witty cartoonist and a master of the doodle, and it is perhaps too easy to read The Labyrinth across its surface rather than as an elliptical, modernist, autobiographical endeavor. Working largely through allegory and metaphor, it imparts a sense of Steinberg rather than his life story. He recurs as a midcentury Don Quixote who jousts with unequal foes. He is the fisherman who unwittingly land a catch that could swallow him whole. He is the artist at the easel whose line escapes the canvas and leads a haphazard life of its own around the page. He is both the hand that makes the drawings and the subject of them; he leads the line and is led by it, so that, in labyrinthine fashion, he shows himself to himself.

Nicole Rudick’s writing has appeared in the New York Review of Books, the Paris Review, Artforum, and elsewhere.