Nikki Shaner-Bradford

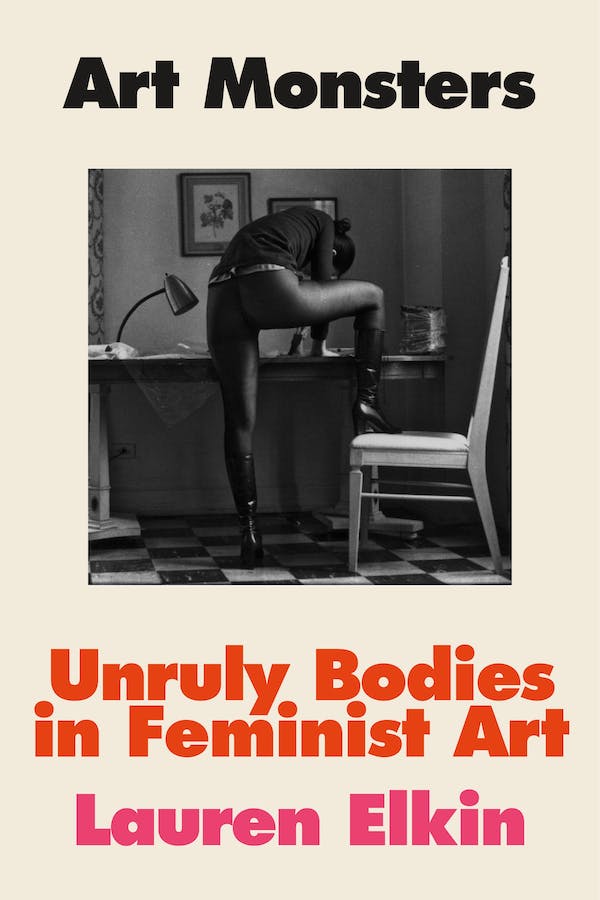

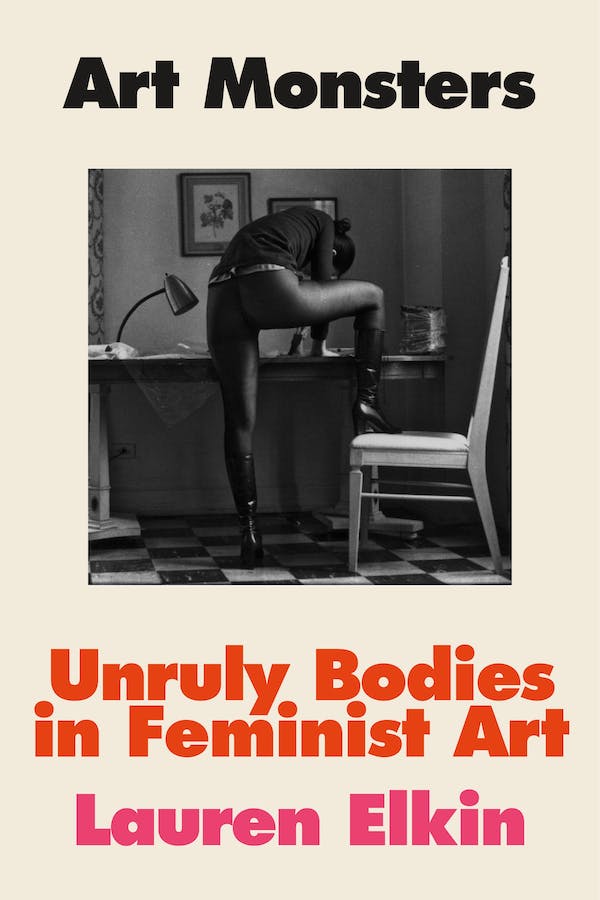

NIKKI SHANER-BRADFORD: Your new book Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $35) riffs on a term many people first heard in Jenny Offill’s 2014 novel, Dept. of Speculation. Offill’s narrator says, “My plan was to never get married. I was going to be an art monster instead. Women almost never become art monsters because art monsters only concern themselves with art, never with mundane things.” What did you think of Offill’s term, and what does it mean in your book?

AS A CHILD, I dreamed I would one day become a fashion designer. It’s one of those gigs, like astronaut or firefighter, that seems fun until you get too old to overlook the occupational hazards. For fashion, the dangers have long been hidden. In recent years, news coverage of “fast fashion,” a deceptively light term for cheaply manufactured clothing that pollutes landfills and oceans while exploiting and endangering workers, has proliferated—while solutions have not. The disconnect is understandable though hardly excusable: consumers look to material goods to change the way they feel, and fashioning a new sense of self doesn’t usually

WHEN I FINISHED MY FIRST READ of Which as You Know Means Violence, critic Philippa Snow’s debut “on self-injury as art and entertainment,” I returned to my own cultural hallmark of suffering, the 2006 film adaptation of The Da Vinci Code. Reading Snow’s analysis of artist Chris Burden’s 1974 crucifixion atop a Volkswagen Beetle alongside the comical stunts of Johnny Knoxville and his squad of Jackass pranksters, I thought frequently of Paul Bettany’s fanatical Silas, who torments himself to such extremes that he plays at the brink of absurdity. Silas spends most of his screen time scurrying around church cloisters in