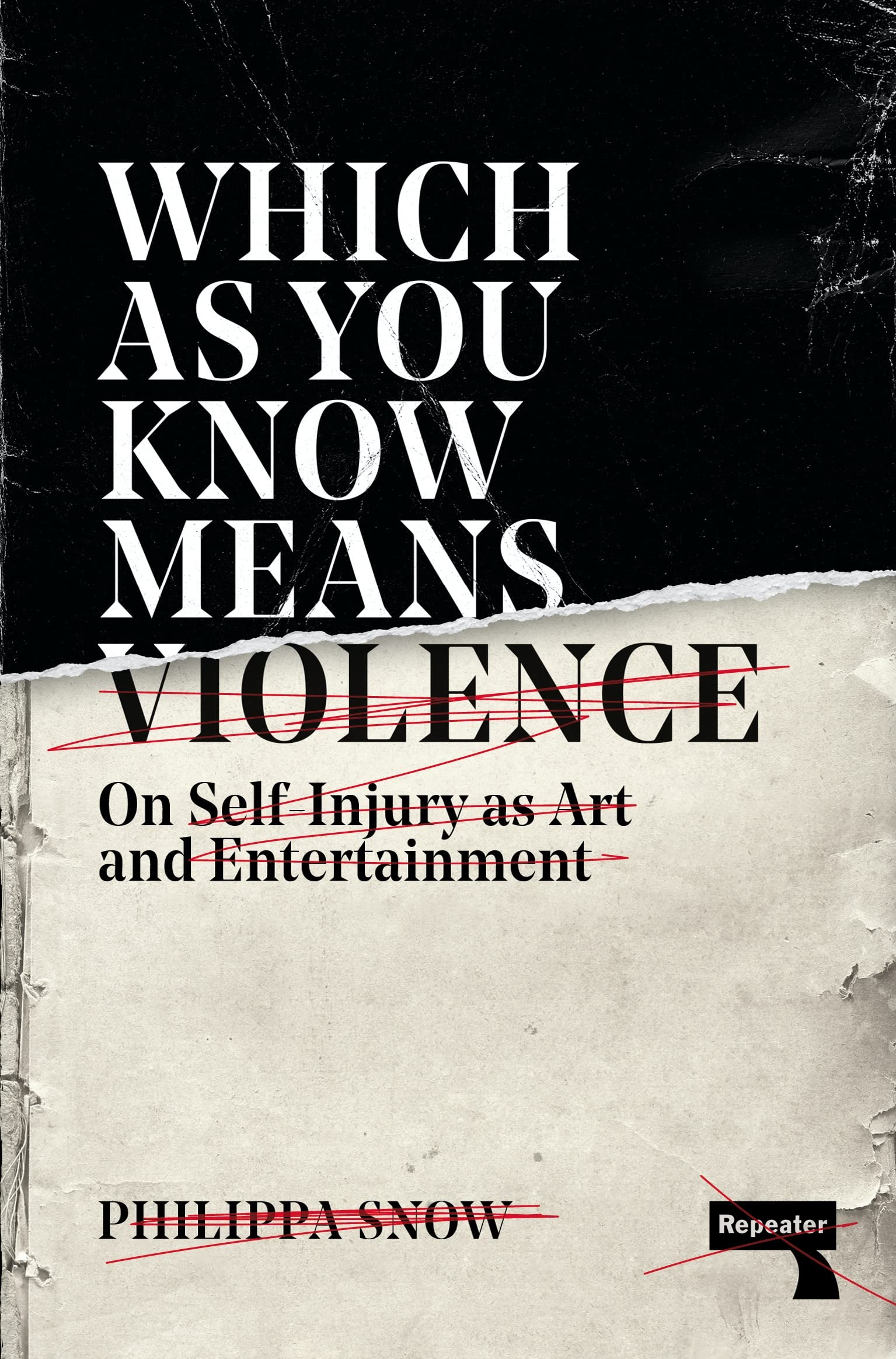

WHEN I FINISHED MY FIRST READ of Which as You Know Means Violence, critic Philippa Snow’s debut “on self-injury as art and entertainment,” I returned to my own cultural hallmark of suffering, the 2006 film adaptation of The Da Vinci Code. Reading Snow’s analysis of artist Chris Burden’s 1974 crucifixion atop a Volkswagen Beetle alongside the comical stunts of Johnny Knoxville and his squad of Jackass pranksters, I thought frequently of Paul Bettany’s fanatical Silas, who torments himself to such extremes that he plays at the brink of absurdity. Silas spends most of his screen time scurrying around church cloisters in monk’s robes and a bloody cilice, or flagellating his back in penance, a commitment to suffering so all-consuming and ridiculous that, by his third murderous jump-scare, it’s a challenge not to laugh mid-flinch.

Which as You Know Means Violence is split into four essays, best read in succession, with each of the final three answering a question posed by its predecessor. The first wonders what kind of person injures themselves for art? The answer (mostly young white men) inspires Snow’s next inquiry, how is self-injury gendered? The final two essays can be boiled down to why is this funny? and what about death? Snow’s debut fits onto the same shelf that holds Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others (2003) and Maggie Nelson’s The Art of Cruelty (2011), but her focus on self-inflicted suffering complicates lingering questions of audience. This isn’t one of Snow’s stated aims, but the essays circle and formulate one possible answer to the question that runs through all of these books: Why watch?

Snow’s approach is selective compared to Nelson’s indexing and light-hearted against Sontag’s philosophical prose. It’s the kind of book that does the homework for you but doesn’t brag about it. The chosen works can be loosely attributed to contemporary artists, stuntmen, or both, and Snow frequently questions whether there’s much difference between them. Many of her artists debuted in the 1970s or ’80s, including Chris Burden, Ron Athey, and Bob Flanagan, while the stuntmen or pranksters (with the pratfall-auteur exception of Buster Keaton) land squarely in the ’90s and 2000s, beginning with the Jackass gang and hearkening back to a young Harmony Korine before touching, briefly, on today’s devil-on-demand Logan Paul. The majority also tend to be cis white men, with Johnny Knoxville and Jackass taking a central role, though Marina Abramovic´ appears throughout as a helpful counterweight: a self-serious, female performance artist in contrast to Knoxville’s all-male fart joke heard round the moma. Intentionality becomes something of an aside; the pain is the point. Snow is clear: art can be an accident, and a large selection of the work she discusses tends to be, with YouTubers like Paige Ginn and Logan Paul appearing alongside established artists like Nina Arsenault and Bob Flanagan.

Early in the first essay, Snow draws a parallel between Tolstoy’s definition of art, in which the artist “hands on to others feelings he has lived through,” and Knoxville’s self-explanation in 2021, “I feel like the injuries, I share with people.” It takes a certain kind of person to self-injure for art (or fun): someone drunk on youth and disillusioned with social norms, halfway between a “madman” and a “saint” (or a “martyr,” if the artist is a woman). But the audience remains amorphous. Jackass was popular with female viewers, too, Snow notes, and it’s curious, in an examination of self-injury as art, a type of suffering that requires an audience, that Snow devotes less space to the passive half of this dynamic. (Sontag would likely interrupt here to remind us that seeing is an act.)

One can hardly achieve sainthood in a vacuum. Courting death might be the actions of a maniac, but courting death for entertainment initiates a kind of Fight Club–style catharsis, in which both artist and audience are permitted some relatively safe proximity to chaos and destruction. The equation sketched by Snow is a combination of survival and remove; if the opposite of schadenfreude is horror, we experience both when confronted with self-inflicted pain, confused by a suffering doled out by the sufferer. While self-injury offers agency to the artist, it also provides a unique transference for viewers. Chris Burden and Johnny Knoxville create a “voodoo” effect by exorcising the trauma of the Vietnam War or 9/11, respectively, through harming their own bodies. Abramovic´ and Arsenault, Snow argues, might do something similar with gender.

In one of the Burden pieces Snow cites, the artist spent ninety days on a high platform in a gallery, eavesdropping on the audience below. In response, a young attendee reportedly compared him to God, who “doesn’t answer, but he can’t help listening.” The alternative, in the words of Fight Club’s Tyler Durden, is “to consider the possibility that God . . . does not like you.” Sontag, Nelson, and Snow released their books at notable moments in American history—at the turn of the century, in the wake of the 2008 election, and during the long pandemic. Reading their books, one is inclined to think that every time is worse than the last, that there is always more war and suffering, and that “now more than ever” is a redundant and absurdist phrase. Nature remains indifferent, though it, too, suffers at human hands.

In the endeavor to approach self-injury as a kind of absurdist theater, which seems to be Snow’s intention, though she never outright declares it, it’s tempting to read Albert Camus’s “The Myth of Sisyphus” onto a figure like Knoxville. Camus’s essay asks whether suicide is a solution to human suffering, and ends up articulating a philosophy of the absurd in which, rather than die voluntarily, or commit to some false hope against despair, one accepts “the certainty of a crushing fate, without the resignation that ought to accompany it.” Another way of reading Camus is to say that the best thing to do, in the face of lifelong suffering and eventual death, is to commit wholeheartedly to a bit.

Now on my third or fourth viewing of The Da Vinci Code, I continue to be unable to stomach Silas’s scenes of suffering, and yet when his fateful death arrives, I am always overcome by his wide-eyed horror at being shot, the sudden knowledge of his ephemerality. There will be no salvation in death for Silas. Quickly losing control of his body, he becomes unstuck from time and flesh, echoing the accusation once wielded by his father: soy fantasma. I am a ghost.

In Snow’s final essay on the possibility of death as art, she determines that the sobering finality of death, and the emotional gulf between the dead and the living, confines art to the space of survival. “A body of work can, after all, outlast a body,” she writes. Sustained self-injury becomes a gesture of mortality dressed up in a delusional pantomime of immortality. Snow describes Logan Paul’s vlog of the Aokigahara forest, in which the YouTuber stumbled across (and filmed) a man who died by suicide, as “a metaphor for the intrusion of the idea of death into even our most lightweight attempts to distract ourselves from our own fragility.”

In Regarding the Pain of Others, Sontag declared “photographs of the suffering and martyrdom of a people are more than reminders of death, of failure, of victimization. They invoke the miracle of survival.” But if bearing witness to human survival breeds reverence, then witnessing survival against self-inflicted odds offers something else entirely, a kind of revolt. Despite what internet theorists might want you to think about generational apathy, it’s not news that most of us spend our lives oscillating between raw openness and closed detachment. How does one embrace the world without running into an outstretched fist? One solution is to punch yourself first.

In the final pages of Which as You Know Means Violence, Snow quotes the father of Bob Flanagan. Watching his son commit acts of s/m and self-injury, he says, “I feel the pain. Then he lands on his feet, and I’m proud, and all of a sudden everybody’s applauding. . . . I think he’s doing this to say to God, or whoever’s out there: you son of a bitch.” If the absurd requires revolt, a process Camus describes as a kind of granularizing of the present, then nailing a hole in one’s arm or penis, and laughing, might be one way of achieving this. Imagining Sisyphus happy is, after all, both comedy and comfort.

While following the progression of Which as You Know Means Violence, I found myself wishing that Snow had devoted essays to two additional questions. First, and most glaringly, what of race? Snow briefly addresses the relative racial homogeny of self-injurious art using the Black artist Pope.L as a counterargument, but this inquiry spans the space of a couple paragraphs in the first essay. Whiteness might privilege its practitioners with the ability to be “casually brutal” or “showily careless” with their bodies, as Snow argues, but the use of self-injury by women and LGBTQ artists, as a tool to excoriate identity and oppression, also suggests that the agency it lends can be empowering, revealing, and/or subversive. Just because some self-injury is less casual viewing than Jackass, does that make it any less of a revolt? By glossing over the question of race, Snow misses an opportunity to consider the capacity for self-injury to make communal pain legible on the body, and, conversely, how the fragmentary nature of generational trauma might complicate individuated acts. Reception of Pope.L’s Crawl, in which the artist dragged himself through the streets of New York in a suit, was controversial rather than cathartic, especially with one Black viewer who considered the piece traitorous, perpetuating the degradation and violence of white supremacy. (Lest we forget that in Toni Morrison’s Beloved, ghosts do haunt the living, and an exorcism is not an easy fix.)

Additionally, I recalled the spate of cutting content and accounts that popped up online in the 2000s and 2010s, which created a kind of image economy and corresponding community out of individual acts of self-harm. Though Snow touches on personal trauma among her artists, particularly in her explorations of Ron Athey and Bob Flanagan, I wondered about practitioners of self-harm who posted their injuries after the fact, without theorizing their actions or conceiving of themselves as artists. Perhaps either of these hypothetical essays would have led their reader to different conclusions about self-injury as a site for communal pain, rather than voodoo individualism or cathartic empathy at a distance. I reread Snow’s essays in an afternoon and wished for more. If we’re lucky, perhaps she’ll pull a Sontag and offer a second set.

Nikki Shaner-Bradford is a writer who lives between Paris and New York.