Parul Sehgal

Transit, Rachel Cusk’s cerebral and very charismatic new novel, begins like so many of the best stories: with an act of foolishness. Our narrator, fragile, aptly named Faye, goes into debt to buy a crumbling flat. She sends her children to live with their father and embarks on an expensive renovation, infuriating her neighbors, and living for a lonely season in a sort of mausoleum. “Everywhere I looked I saw skeletons,” she says, “the skeletons of walls and floors, so that the house felt unshielded, permeable, as though all the things those walls and floors ought normally to keep out

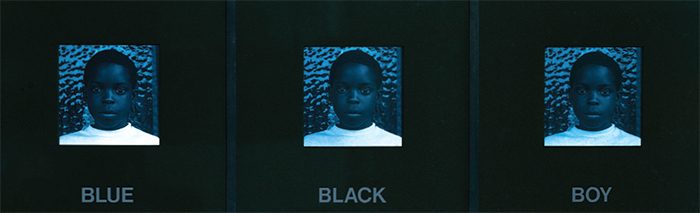

Claudia Rankine’s Citizen is an anatomy of American racism in the new millennium, a slender, musical book that arrives with the force of a thunderclap. It’s a sequel of sorts to Don’t Let Me Be Lonely (2004), sharing its subtitle (An American Lyric) and ambidextrous approach: Both books combine poetry and prose, fiction and nonfiction, words and images. But where Lonely was jangly and capacious, an effort to pin down the mood of a particular moment—the paranoia of post-9/11 America and the racial targeting of black and brown men in those years—Citizen’s project is more oblique, more mysterious.

AS AN INSTITUTION, the family is in the curious position of being regarded as both crucial to human survival and inimical to human freedom. It bears a note of bondage down to its root; family, that wonderfully warm, nourishing-sounding word (it’s the echo of mammal, mammary, mama, I suspect), derives from the Latin familia, a group of servants, the human property of a given household, from famulus, slave. Since its beginnings, family has carried this strain of being bonded—and not just in body but in imagination. “In landlessness alone resides the highest truth, shoreless, indefinite as God,” says Ishmael, setting

The known risks of laughter, according to a recent study published in the British Medical Journal, include dislocated jaws, cardiac arrhythmia, urinary incontinence, emphysema, and spontaneous perforation of the esophagus. None of this, I suspect, will be news to readers of Lorrie Moore, who has never taken laughter lightly. In her work, humor is always costly and fanged. Here’s her idea of a joke (from her 1998 story collection, Birds of America): found among the rubble of a plane crash is a pair of “severed crossed fingers.”

Call it the Curious Case of Marianne Moore. She was an American Athena, spawned by no particular school but championed by every major poet of her generation. Her poems are Wonderlands populated by spiny creatures and pools of sudden malice, where language is precisely used and used precisely. She was also a beloved pop icon, instantly recognizable in her tricorne hat. She threw the first pitch for the Yankees in 1968, palled around with Norman Mailer and Muhammad Ali, and was invited by Ford to name a new car. The New York Times noted her death in 1972 on page

When Anne Carson was a child, she read Lives of the Saints and adored it so much she tried to eat its pages. The Canadian classicist and poet has never lost this desire to merge with the text; if anything, she’s created forms that allow her to eat as many pages as she possibly can. In her translations and recastings of the classics, she enters the books she loves, tilts and deranges them and makes them her own. Nor has she lost her appetite for the physicality, the thingness, of a book. She eulogized her brother, Michael, in Nox (2010)—a

Pity; they used to be such nice girls. Leah Hanwell and Keisha Blake grew up together in a grim housing estate in North West London. They acquired university degrees, good jobs, political convictions, pretty husbands. And they’re miserable. Now in their mid-thirties, they’re pickling in bile and coming apart. Leah has become fixated on a local woman who bilked her out of thirty pounds. She’s secretly taking birth-control pills, scuttling her husband’s plans to start a family. Keisha, who’s gotten posh and changed her name to Natalie, is spending a bit too much time on a website catering to people

Readers are not created equal. Frances Ferguson observed, rather dolorously, that the “reader can only read the texts that say what he already knows,” but let’s be frank: There are gifted—or maybe just thirstier—readers among us who, by dint of stamina or plain need, won’t be stymied by boredom, offense, incomprehension. There are varsity readers, and then there is Maureen N. McLane, a poet, professor, and prizewinning critic. To read McLane is to be reminded that the brain may be an organ, but the mind is a muscle. Hers is a roving, amphibious intelligence; she’s at home in the essay

Isaiah Berlin split intellectuals into two groups: foxes, who know a great deal about many things, and hedgehogs, who know one big thing. But I wonder if there isn’t a third type, too, mysterious and misunderstood: the individual who knows a great deal about one thing—and that thing is herself. Narcissism has nothing to do with it. This is a specialty that usually signals deprivation: In the absence of other people, the self was all there was to study.

Rehan Tabassum is in a bad way. Although, strictly speaking, the trouble isn’t of his making. He’s just got that kind of family—prone to falling in love with the servants, scheming against one another, messing with the wrong fundamentalist and leaving sensitive home videos lying about. The Tabassums, owners of a telecommunications empire in Pakistan, are a brutal, blundering clan grown crooked and strange after years of bending to the will of their autocratic patriarch.