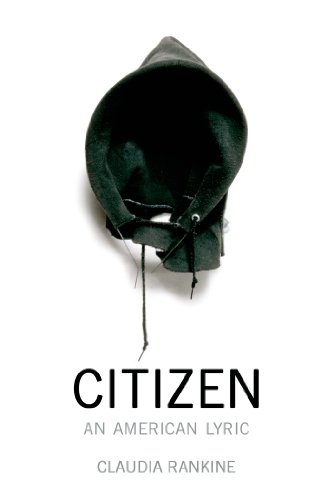

Claudia Rankine’s Citizen is an anatomy of American racism in the new millennium, a slender, musical book that arrives with the force of a thunderclap. It’s a sequel of sorts to Don’t Let Me Be Lonely (2004), sharing its subtitle (An American Lyric) and ambidextrous approach: Both books combine poetry and prose, fiction and nonfiction, words and images. But where Lonely was jangly and capacious, an effort to pin down the mood of a particular moment—the paranoia of post-9/11 America and the racial targeting of black and brown men in those years—Citizen’s project is more oblique, more mysterious.

For the book is, first of all, a surprisingly seductive object. Its pages are slick and pearly, and the full-color images—paintings, TV screenshots, photographs—give it the feel of a gallery catalogue, which, in a way, it is. Citizen guides us from spectacle to spectacle, from a consideration of Serena Williams’s career and the racist taunting she has endured to a beautifully reproduced photograph of Kate Clark’s Little Girl, a sculpture of a hoofed woman; from an elegy for Trayvon Martin to Carrie Mae Weems’s Blue Black Boy, in which three identical blue-hued prints of a boy are presented side by side, one labeled BLUE, one BLACK, one BOY. And in the book’s most powerful passages, Rankine reports from the site of her own body, detailing the racist comments she’s been subjected to, the “jokes,” the judgments. It’s what we commonly call microaggressions, what Rankine calls “invisible racism” for how swift and sneaky it is, how ever-present. It is the word uppity. It is the word strident; it’s “No, where are you really from?” It’s stop-and-frisk. It’s what Hilton Als calls “phantasmagorical genocide,” what Kara Walker calls the “perpetual reminder that in this culture a Black body is not safe and my humanity is not real.” It is death by a thousand cuts.

Increasing attention has been paid to microaggressions in recent years. There have been books like Touré’s Who’s Afraid of Post-Blackness? (2011); social-media campaigns like “I, Too, Am Harvard,” in which students discuss comments that have made them feel marginalized on campus; even BuzzFeed lists (“21 Racial Microaggressions You Hear on a Daily Basis”). And there’s “Killing Rage,” a classic of the genre: bell hooks’s 1995 essay about the array of racism she encountered on a trip to New York, a scalding piece of writing that begins with the indelible “I am writing this essay sitting beside an anonymous white male that I long to murder.” Rankine works in a cooler register. She renders her encounters in language rinsed of color, cant, and emotion. Her descriptions could be courtroom testimony: “The man at the cash register wants to know if you think your card will work. If this is his routine, he didn’t use it on the friend who went before you.” “You have already settled into your window seat on United Airlines, when the girl and her mother arrive at your row. The girl, looking over at you, tells her mother, these are our seats, but this is not what I expected.” “The woman with the multiple degrees says, I didn’t know black women could get cancer.”

It’s the framing that gives the vignettes their teeth: By telling us these stories, some of which she borrowed from family and friends, in the second person, Rankine builds her book on shifting sands—the reader is never immediately sure who in the story is black or white, whom to identify with, whom to trust or fear.

That indeterminacy, that unsettling openness in the text, recalls the paranoia racism evokes (“Did she really just say that? Did I hear what I think I heard?”), and it’s an unusual feature of writing about race. From Harriet Jacobs’s 1861 memoir to James Baldwin’s essays to Teju Cole’s rereading of Baldwin’s essays, the dominant mode has been pedagogic, messianic: the writer trying to persuade white America of her humanity, trying to save its soul.

But Rankine keeps a different faith. In her work can be felt the opposing strains of wanting, and wanting badly, for her writing to serve some practical purpose (“I tried to fit language into the shape of usefulness,” she writes in Don’t Let Me Be Lonely) as well as something more anarchic. When she quotes the filmmaker Claire Denis—“I don’t want to be a nurse or a doctor, I just want to be an observer”—it isn’t critically. Rankine is profoundly interested in witnessing how power and pain move through the body and the body politic—but without prescription. She doesn’t declaim. She rarely consoles. Instead she creates a space for readers to engage with their own preconceptions, fears, and hostilities. It’s the visual artists she seems most in conversation with, those who approach race at a slant—Weems as well as Kehinde Wiley and Yasumasa Morimura—with their reliance on repetition and juxtaposition, their ability to bring the viewer into the work. The plainness of Rankine’s prose, the deliberate flatness of her second-person set pieces, recalls Kara Walker’s silhouettes, those panoramic nightmares of plantation life mounted on bare white walls, on which the viewer’s shadow also falls. So do we enter Citizen. We are invited, we are implicated.

We are also disoriented. Rankine scatters elliptical, enigmatic images and poems throughout. Take Clark’s sculpture Little Girl, a beguiling creature with the body of a deer and the face of a wary woman. Along her face, something glints, like tears or jewelry. They are tiny nails drilled into the skin. She appears to be the victim of some enchantment, one of those women from myth punished for spurning the gods. She huddles low on the page, puzzled and puzzling—until we read on and the riddle seems to reveal itself.

Racist language is, after all, itself a kind of enchantment, a kind of spell. And Rankine stages her encounters so we can see, almost in slow motion, how it enters and lodges itself in the body, and what havoc it causes. There is first the shock (“Did I hear what I think I heard?”), the somatic response (“Certain moments send adrenaline to the heart, dry out the tongue, and clog the lungs”). The taste it leaves behind (“a bad egg in your mouth”), that feeling of being marked, befouled (“puke runs down your blouse”). And confusion, even self-blame: “You are in the dark, in the car, watching the black-tarred street being swallowed by speed, he tells you his dean is making him hire a person of color when there are so many great writers out there. You think maybe this is an experiment and you are being tested or retroactively insulted or you have done something that communicates this is an okay conversation to be having.”

Rankine reminds us that racism is an intimate violence—its perpetrators are not just institutions or strangers who deny our humanity but friends, colleagues. It is language that renders one “hypervisible,” she writes, quoting the philosopher Judith Butler. The body is made a public place, subject to scorn, suspicion, regulation. This sort of hypervisibility challenges not only the ability to feel welcome in a given space—at a job, in a neighborhood, in a country (“I remembered myself as a very small boy, already so bitter about the pledge of allegiance that I could scarcely bring myself to say it, and never, never believed it,” wrote Baldwin)—but, even more perniciously, one’s right to one’s own body. “Where is the safest place when that place / must be someplace other than in the body?” Rankine writes. Racism imparts a kind of homelessness: “The worst injury is feeling you don’t belong so much / to you.”

Deftly, Rankine links microaggressions to the more explosive cases of racial violence: the shootings of Trayvon Martin and Mark Duggan, the killing of James Craig Anderson, a black man who was beaten and run over by a group of white men in a pickup truck. Citizen is a tacit response to both those who wonder how such things can happen and those who insist such things happen elsewhere. Rankine shows us how dehumanization works—over brunch, in the checkout line, at the university. At the hands of people you admired and trusted. She traces the ions, the shocks and currents that become the storm.

When a teenager named Michael Brown was killed in Ferguson, Missouri, this past August by a police officer—shot at least six times, twice in the head—the city erupted in grief. Rankine went to Ferguson. She wanted to talk to people, she said in an interview with the New Yorker, to “ask people what they’re thinking right now and how they’re feeling.” Her remarks are full of sorrow and puzzlement: “When I’m walking around, I’m sometimes just perplexed at people who seem like everyday people, people who are on juries, who are in the police force, who are in control of my life in many ways.”

That is the sting Citizen leaves behind. Rankine is able to sit with the questions she cannot answer. But even if there is no solace on offer, this work of careful, loving, restorative witness is itself an act of resistance, a proof of endurance. “Sometimes we are blessed with being able to choose / the time, and the arena, and the manner of our revolution,” wrote Audre Lorde. “But more usually / we must do battle where we are standing.”

Parul Sehgal is an editor at the New York Times Book Review.