Rebecca Panovka

EARLY IN ELIF BATUMAN’S NEW NOVEL Either/Or, she quotes a blurb on the front of Kazuo Ishiguro’s An Artist of the Floating World, extracted from its 1986 review in the New York Times. “Good writers abound—good novelists are very rare,” the critic theorizes, deeming Ishiguro “not only a good writer, but also a wonderful novelist.” For Either/Or’s narrator, the distinction comes as a shock. Since she was young, Selin has aspired to become a novelist, and she views much of her life to date as training for that vocation. Assessing herself according to the reviewer’s implied rubric, Selin realizes that

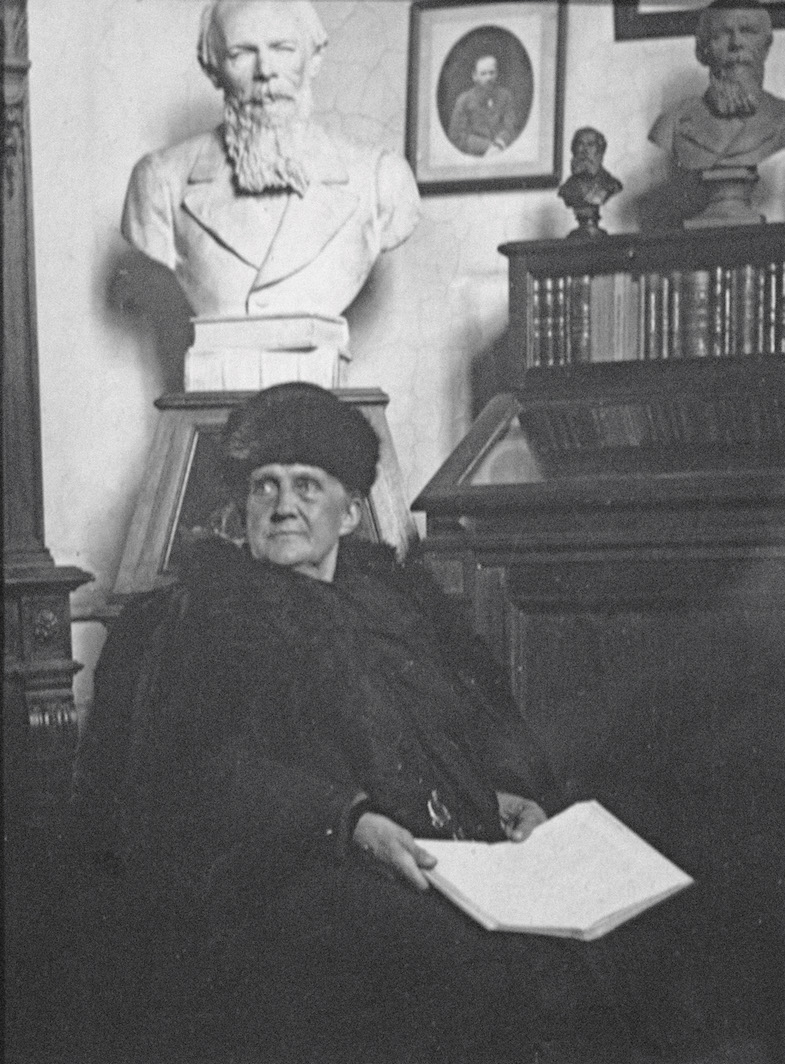

IN THE FALL OF 1866, FYODOR DOSTOYEVSKY FOUND HIMSELF barreling toward every writer’s worst nightmare: a deadline he couldn’t ignore. Having signed an ill-advised contract to avoid a trip to debtor’s prison, he now owed the publisher Fyodor Stellovsky a new novel of at least 160 pages by November 1. If he failed to deliver, Stellovsky would be entitled to publish whatever Dostoyevsky wrote over the next nine years free of charge. A more practical man might have spent his summer on the project for Stellovsky, but Dostoyevsky was simultaneously preparing segments of Crime and Punishment for serialization, and his

WHEN I WAS EIGHT OR NINE, my father bought an encyclopedia. To him, maybe because there had been one in his childhood home—a prized possession his parents had bothered to box up and ship when they immigrated in the 1970s—owning an encyclopedia was some sort of milestone, a marker of adulthood. I had trouble grasping the potential utility. Why do you need that, I asked, when you can use Wikipedia? This resulted in a game: we would come up with an arbitrary topic or question (What are the names of Jupiter’s moons? What was Kublai Khan’s love life like?), and