EARLY IN ELIF BATUMAN’S NEW NOVEL Either/Or, she quotes a blurb on the front of Kazuo Ishiguro’s An Artist of the Floating World, extracted from its 1986 review in the New York Times. “Good writers abound—good novelists are very rare,” the critic theorizes, deeming Ishiguro “not only a good writer, but also a wonderful novelist.” For Either/Or’s narrator, the distinction comes as a shock. Since she was young, Selin has aspired to become a novelist, and she views much of her life to date as training for that vocation. Assessing herself according to the reviewer’s implied rubric, Selin realizes that her facility with language, her sparkling insights and clever turns of phrase, may not be sufficient. “It was what I had been counting on,” she thinks. “My sense of being a good writer. My stomach sank with the knowledge of how wrong I had been.” This is in some sense the anxiety that haunts Either/Or: Batuman is demonstrably, incontrovertibly a good writer—but is she a good novelist? (And what is a good novel anyway?)

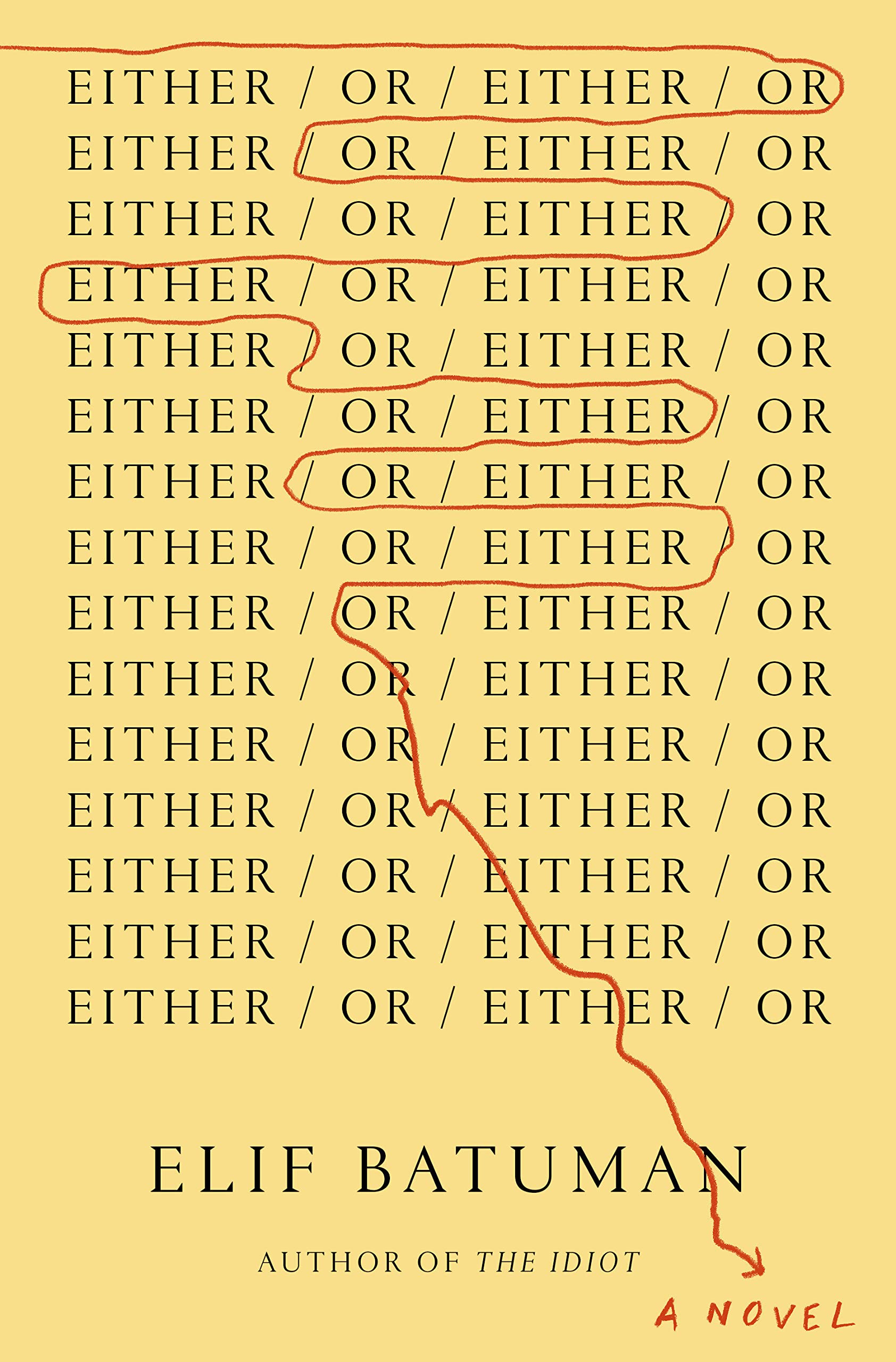

Either/Or picks up where Batuman left off at the end of her autobiographical first novel, The Idiot, which chronicled her avatar Selin’s first year at Harvard in 1995. In its sequel, she has traded Dostoyevsky for Kierkegaard, freshman year for sophomore, a summer abroad in Hungary for one in Turkey. Selin continues to read, to navigate friendships and not-quite-romances, to make amusingly blunt observations about the world of academia—and, increasingly, about the adult world of men and women.

Perusing the course catalogue, she wonders if the departments and majors are organized correctly. “Why were the most important subjects addressed only indirectly?” she asks. “Why was there no department of love?” Later, she thinks, “I wished there was a class where they could teach you how to calculate the right time to die.” She has the sense that college courses, even in the literature department, are structured to talk around rather than explicitly address what she most wants to learn—professors, she delightfully points out, betray a “characteristic delight at not imparting information”—but that their syllabi can be mined for the right lessons anyway. There is no knowing intellectualism to the way Selin encounters texts. Hers is a perhaps naive and almost nose-thumbingly unacademic style of reading. As she turns her attention to a series of novels (Eugene Onegin, The Sorrows of Young Werther, Nadja), Selin is not only reading for form or content; she is iterating ideas about how to live, and how to write—and how these two things overlap. It’s an appealingly forthright picture of the young life of the mind: how we learn to discuss books in a classroom setting while privately asking of them something much more delicate, more personal.

Here is the typical pattern of Selin’s reading, and by extension Batuman’s prose. Selin is exposed to an idea or a text, she connects it to something in her life, she thinks through how the text can extend or revise her prior perceptions about a person or situation, and then, often, she returns to the text to evaluate it on the basis of how it has furthered her insights. She tends to draw almost automatic one-to-one correspondences between people in her life and characters in books; many of Batuman’s short sections begin with a text and lead back to Ivan, the unrequited crush from The Idiot. Batuman sees the humor in this hermeneutics, and she avoids dressing it up as proper method. It’s endearingly clunky analysis—and, in its own right, a theory of how we experience literature, as a fun-house mirror in which to glimpse our preexisting beliefs as well as our insecurities. Concerned she is undesirable to men, for instance—she is, at nineteen, anxious to have her first kiss—Selin notes of Anna Karenina, “There were no women in that book with whom nobody thought about having sex.”

As Selin conducts her exercise in reading personally, she also becomes a woman with whom people think about having sex. Her first few times are decidedly unromantic. “Now, I was starting to get the feeling that the in-and-out motion was sex—that there wasn’t anything else after that,” she observes mid-coitus. Afterward, she concludes, “That’s what sex was. I tried to assimilate this new information—to accord it its correct importance.” Intercourse is, for her, an acquired taste, like wine or Elizabethan drama. “Yes,” she decides, “understanding the point of sex felt just like understanding the point of Shakespeare.” But ultimately the point of having sex, for Selin, is no longer feeling that her life is failing to measure up against the benchmark of canonical literature. Falling in love, she knows, is “the essential feature of a novel,” and sex feels equally crucial. “Was it sex—‘having’ sex—that would restore to me the sense of my life as a story?” she wonders.

Yet in most stories, she finds, sex tends to end badly for women. In novel after novel, Selin encounters the figure of the woman seduced and betrayed, the woman stymied by love, the woman abandoned and destroyed. “It couldn’t be that, again—could it?” she thinks when a story trends in this familiar direction. “Was that what everything was about?” For women, she sees, love entails a loss of autonomy, a surrender of self to the male beloved. When her best friend Svetlana starts dating a classmate, Selin mourns the development. Svetlana “would never again be what she had been, not in my life, and not in her own,” Selin explains. “This boyfriend, or his successor, would restrict her activities, her thoughts.” The social structure of heterosexual love may be inherently constraining to women, but to “just ignore society and dumb men” is unthinkable. “Love wasn’t a slumber party with your best friend,” she writes. “Love was dangerous, violent, with an element of something repulsive.” There are hints, throughout, that Selin wishes she could avoid the trap of heterosexuality and seek a different kind of love—a love that is a slumber party with your best friend, a love that is not repulsive, a love that is about something other than male seduction and female abandonment, and sex that is not just “in-and-out”—but that, it being 1996, she lacks the vocabulary to do so.

An awareness of Selin’s conceptual limitations is never far from the surface of Either/Or. On almost every page, the reader senses a second presence: a more knowing Selin (one who, like Batuman, has both learned to read in a more sophisticated way and found an alternative to heterosexual relationships) hovering over her former self with an embarrassment that’s aged into bemusement. As Selin appraises sex and love and literary works, her uncertain, ingenuous voice lies somewhere between charming and grating. At times, her cluelessness seems exaggerated, as if to reassure the reader that no matter how awkward we imagined ourselves to be in college, at least we weren’t quite as awkward as Selin.

How much that naivete bleeds into her first-person prose style is an open question. It’s clear Batuman is taking pains not only to read literature as though she did not have advanced degrees in the subject, but also to imagine herself back into a frame of mind in which the rhetorical question is the most natural way to pose a new thought and a cliché the best way to describe a strong emotion. Her “stomach sank,” recall, at the contrast between the wonderful writer and the wonderful novelist, and elsewhere she experiences a “sinking horror” and “a sinking feeling.” Her heart, meanwhile, has a tendency to pound: “My heart was pounding. There was a book about this?” “I logged out, my heart pounding.” “I felt my heart pounding.” “My heart was pounding faster than the blinking cursor.” “But did it matter, wasn’t my whole rib cage pounding?” Fair enough: stomachs sink, hearts pound, and, as Selin recounts at one point, “Happiness swept over me.” (Other things that “wash over” the narrator include “doom,” and “some treehouse-related feeling of pride and seclusion.”)

Whether or not Selin is a wonderful writer, what she wants is to become a wonderful novelist. And to do that, she’s under the impression she’ll have to dispense with the material she most wants to chronicle: herself. Indeed, Selin seems particularly preoccupied with the widespread dictum that it is “self-indulgent” to write about one’s own experience. In an early creative writing class, she learned that “writing what you were already thinking about wasn’t creative, or even writing. It was ‘navel-gazing.’” Autobiographical writing, meanwhile, is “childish, egotistical, unartistic, and worthy of contempt.” Rather than transcribing one’s experience, the true novelist “had to disguise it, turn it into art,” she writes. “That’s what literature was.” It is Selin’s instinct to document the characters in her life and the books she’s reading, but she thinks it would be unacceptable to turn those notes into a novel. “It felt shameful to be so unartistic and self-obsessed, to not want to invent richly fictional characters,” she admits.

This type of confession serves a dual purpose, not only inoculating the text against potential criticisms, but cloaking it in the mantle of transgression: of course, the novel we are reading now is the one Selin thinks she’s not allowed to write. She can’t have a narrator with a Turkish name, she tells us, “because I didn’t want to seem like I was constantly harping on being Turkish.” She wishes she could write a book about her experience of reading—“where I could explain each line, and how it applied in such a specific way to things that had happened in my life”—but has decided it’s hopeless: “I knew that nobody would want to read such a book.” In reference to a topic that’s taken up the past several sentences, she says, “I would never write about that. It was enough I had wasted the time once. I would never waste more time by writing about it.”

Amid Batuman’s self-referential winks, we’re meant to watch Selin rejecting inherited rules for what a novel should be, and determining an alternative narrative form. From the titular Kierkegaard work, she draws the idea of the “aesthetic life,” which she comes to view as “an algorithm”:

In any real-life situation, I would pretend I was in a novel, and then do whatever I would want the person in the novel to do. Afterward, I would write it all down, and I would have written a novel, without having had to invent a bunch of fake characters and pretend to care about them.

While this methodology begins as an irreverent protest against the charge of self-indulgence, it also becomes a feminist commentary on the romantic heroines whose downfalls have increasingly disturbed Selin. In Either/Or’s closing passage, she reads Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady and identifies strongly with the central figure of Isabel Archer, who finds herself stuck in an unhappy marriage, “just like Tatiana” in Eugene Onegin. If the lives of Isabel and Tatiana—not to mention Emma Bovary, Anna Karenina, et al.—had “gone wrong,” she reasons, they had in some aesthetic sense succeeded, insofar as they lent structure and pathos to great novels written by men. But “what good had that done them?” she thinks. “They hadn’t known that their lives were actually the plot of The Portrait of a Lady or Eugene Onegin.” In Portrait, Selin argues, James has to explain that Isabel has “no talent for expression” because “if she could write a book, he would be out of a job.” Selin, by contrast, does have a talent for expression: “Nobody was going to trick me into marrying some loser,” she decides, “and even if they did, I would write the goddamn book myself.”

To be both heroine and author, the person who might be seduced or betrayed or abandoned or stranded in a bad marriage and the person who converts those events into art—it’s an epiphany. “Was this the decisive moment of my life?” she asks. “It felt as if the gap that had dogged me all my days was knitting together before my eyes—so that, from this point on, my life would be as coherent and meaningful as my favorite books.”

As coherent and meaningful, perhaps, but more self-conscious. In his preface to Portrait, James assures the reader that Isabel Archer is a product of pure invention. To know where any creation comes from, he writes, one would have to do “so subtle, if not so monstrous, a thing as to write the history of the growth of one’s imagination.” James means this as a throwaway line, but Selin latches onto it. “I was going to do the subtle, monstrous thing,” she resolves. “I was going to remember, or discover, where everything came from.” That, ultimately, is Selin’s project: to live a life that is as coherent as a novel, in which everything is tied back to its intellectual source. By the end, I’d been convinced of the merits of Batuman’s experiment in life-as-art-as-art—its theoretical underpinnings, its value as feminist critique. But, if I can adopt Selin’s inquisitive mode of reading for a moment: Why recount at length the thrill of encountering The Portrait of a Lady and then spend pages defending the decision not to attempt such a feat? If only because Batuman is a wonderful writer, I hope—selfishly—that she sets out to write a wonderful novel next.

Rebecca Panovka is a writer and coeditor of The Drift.