When a young, Boston-based musician named Charles Thompson—soon to be known by the nom de guerre Black Francis—needed a bassist for his fledgling group the Pixies, he ran a classified ad reading, “Seeking bassist for rock band. Influences: Hüsker Dü and Peter, Paul & Mary.” With hindsight, Thompson’s stylistic coordinates—which must have seemed pretty mystifying when it ran in 1986—could serve as a fairly accurate description of his band’s sonic palette, if you threw in surf music, science fiction, and Puerto Rico. From Hüsker Dü, he took the pulverizing distortion and trenchant chording of Bob Mould’s Flying V guitar—and the surprisingly melodic wall of sound it generated. (It also didn’t hurt that Mould, like Thompson, was a chubby, average-looking guy who could scream like a banshee.) Citing folk-lite trio Peter, Paul & Mary seems like cheap punk irony, but one can imagine Thompson wanting a more controlled sound than that of his thrashy idols, and perhaps a clear, pretty voice to counter his unhinged bellowing. Kim Deal, later of the Breeders, answered the ad, and the rest was history. The Pixies were adored by post-punks and indie rockers, critics and college students. They didn’t sell many records, but a skinny, sensitive kid in Aberdeen, Washington, was listening very closely.

The story of “alternative rock,” indie rock, or whatever you want to call it largely began with Hüsker Dü, the incomparable Twin Cities power trio, formed in 1979, by Mould (guitar/vocals), Grant Hart (drums/vocals), and Greg Norton (bass/vocals). The name, sans umlauts, derives from a Danish board game (“in which the child can outwit the adult”) and means “Do you remember?” in Danish and Norwegian. Playing faster and louder than anyone in the underground of the time, the Hüskers were initially associated with hardcore—the purist, political, Reagan-era version of punk—and their frenetic, abrasive early sound could be summed up by effecting a temperature drop in an EP title by friends and labelmates the Minutemen: Buzz or howl under the influence of cold. (Nothing in music says “icy tundra” like a Sus2 chord, a perennial harmonic move in Mould songs.) Alienated by the lockstep nonconformity of hardcore (and its attendant machismo and violence), the Hüskers quickly evolved into one of the key bands in rock history, retaining the speed and intensity of their seed genre while incorporating elements of the ’60s and ’70s pop they secretly loved. Their savage 1984 cover of the 1966 Byrds classic “Eight Miles High”—something of an aesthetic mission statement—boasted one of the most harrowing vocal performances ever recorded, with Mould’s primal-scream take on the lyrics eventually degenerating into wailing-child glossolalia.

As friendly hometown rivals the Replacements sang on their early dis song “Something to Dü,” the Hüskers weren’t “nothing new.” Indeed, Mould was less an innovator than an aggregator. Was he the first musician to incorporate ’60s pop melodicism and personal angst into punk rock? No, that was the Buzzcocks. Was he the first screaming fat guy in rock? Nope, that would be Pere Ubu’s David Thomas (though they’d both be outshrieked by Black Francis). Was he the leader of the first “college rock” band? Close, but that title, with its arty-academic connotations, probably belongs to Mission of Burma (Hüsker Dü were too lumpen to write a song about Max Ernst). Nevertheless, Mould reconciled the Beatles and Black Flag—no mean feat—thereby influencing countless future musicians in subgenres he helped midwife: “alternative rock,” thrash metal, emo, pop-punk, and, significantly, grunge (the style that mainstreamed punk in 1991 through the success of Nirvana’s Nevermind).

The Hüskers were blessed with two extraordinary songwriters—Mould and drummer/vocalist Grant Hart. Both gay but not “out” in a conventional sense, the pair started out as friends, became healthy competitors whose creative one-upsmanship led to a superabundance of quality songs, and ended up as bitter, passive-aggressive foes. Many musicians have compared being in a band to a marriage, with all of the institution’s ups and downs, but few bands mirrored the arc of an ultimately unsuccessful marriage more than Hüsker Dü, with Mould as the stern, authoritarian father, Hart as the eccentric, unstable mother, and Norton as the quiet, relatively normal kid caught in between (never mind the handlebar moustache). The music press and the band members themselves (particularly Hart) have periodically fueled the post-divorce acrimony ever since the band’s 1988 dissolution, so much so that gossip and speculation about the members’ feelings for one another have tended to overshadow their musical legacy. (Whether it’s true or not, my favorite of these barbs came from Hart, quoted in a 2005 oral history of the Minneapolis scene in Magnet magazine: “Bob can stink up a room without saying a word. The guy has an intimidation factor that’s exponentially greater than anyone I’ve ever met in my life. He can loathe you through a wall.”) Andrew Earles, author of a 2010 book about the Hüskers, is so self-conscious about not perpetuating this toxic dynamic that he spends most of his introduction bending over backwards to warn potential readers that his volume is not that kind of book.

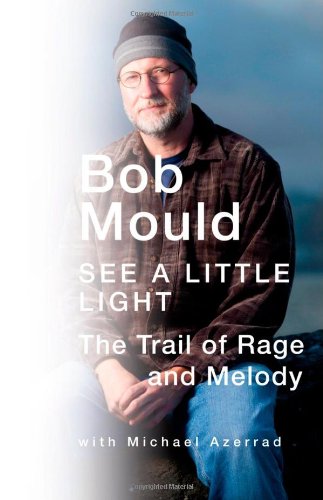

Longtime fans might have hoped that Mould’s memoir, See a Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody, written with Our Band Could Be Your Life author Michael Azerrad, would be at least partly that kind of book, however one-sided. And it is, in places, though most of the salacious details are from his post-Hüsker, openly gay life. Presently in a much happier place than he was for most of his career, Mould seems to have decided to be relatively fair and high-minded about Hart, even if at times his graciousness feels forced. One can almost hear the gritted teeth as Mould writes “clearly one of Grant’s best songs” for the umpteenth time whenever he can’t avoid mentioning a prominent Hart tune from the Hüsker years. And though it’s been vehemently denied over the years by both parties, Mould feels compelled to make clear yet again on page 29 that he and Hart “could be friends, but would never be in love, nor would we have sex.” (The theories about their “relationship” are annoying but understandable: Imagine what Beatles fans would have concocted had Lennon and McCartney been gay.) As a whole, the memoir resembles Mould’s song lyrics: sometimes profound, sometimes ham-handed, rarely subtle; equal parts self-confidence and self-laceration; in a phrase, controlled catharsis. (Ever conscious of what people think about him, Mould riffs on how the word “catharsis” has dogged him throughout his career: “What am I supposed to do with it? When do I get to be happy? Maybe somebody will adapt this book for Broadway: CATHARSIS! starring Bob Mould. The hit play with no ending.”)

Born in 1960 in Malone, New York, a remote upstate burg near the Canadian border, Mould was raised in a dysfunctional working-class home. His father was alcoholic, paranoid, abusive; his mother classically codependent. In the book, Mould reveals that through regression therapy later in life, he realized that he had been sexually abused as a small child by a babysitter, his parents reluctantly confirming this with him on the phone. Growing up, he studied the ’60s pop 45s his dad would buy for him in bulk from a jukebox distributor. Then he heard the Ramones and Johnny Thunders and thought music was something he could actually do in life. A bright, mathematically inclined kid, he won a scholarship to Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota, where he met Hart at a record store where the latter was working. Hart knew Norton, and the three quickly became simpatico and started playing together, founding Hüsker Dü after ousting an inappropriate keyboardist. Mould describes his time with the band as an “eight-year ground war”—not, as you might expect, between the band members, but against Reaganite America, early MTV, ’80s culture generally, and the disposable, substance-free music that stemmed from all of the above.

As chronicled in Azerrad’s aforementioned history of ’80s indie rock, building a network of fans and allies was infinitely more difficult in the pre-Web era. The Hüskers were one of a number of like-minded underground bands that ran tiny labels, helped local up-and-comers, and exchanged knowledge and favors with peers in other cities around the country. “[I]nformation was traded hand-to-hand. Bands kept information in their notebooks, and when we played together, we would sit down and trade information to fill the gaps. This is how we built our community: no fax machines, no cell phones, no internet,” Mould writes, with hard-earned pride. Early on, having already toured the Midwest and West Coast, the Hüskers were anxious about their first East Coast shows because they “didn’t have much of an East Coast notebook.” After a series of brilliant albums on reigning indie label SST, the band became one of the first from this fertile scene to jump to a major label, signing with Warner Brothers in 1986.

This was the beginning of the end, though not because of the evil culture industry and its bean-counting svengalis; the fact was that after seven years of nonstop work, Mould and Hart, never the closest of friends, had become estranged and non-constructively hypercompetitive, battling over the ratio of songs per record and the strict message control Mould tried to exert over the others in press interviews and record-company communications. Their lifestyles diverged as well. Previously a high-functioning alcoholic, Mould had quit drinking before the making of their last LP, 1987’s Warehouse: Songs and Stories, while Hart had acquired a heroin addiction. After the suicide of their bipolar friend and manager, David Savoy, the band’s last few shows on their final tour were disastrous, largely due to Hart’s withdrawal symptoms. When Mould learned of his partner’s addiction, he canceled the remaining dates, and the band fell apart over the following weeks.

The post-Hüsker years have confirmed Mould’s profile as a hard-working survivor. After two solo albums with Anton Fier (Feelies, Golden Palominos) and Tony Maimone (Pere Ubu)—the primarily acoustic, singer-songwriter-ish Workbook and the ponderous, thou-protest-too-much sandblaster Black Sheets of Rain—Mould formed Sugar, another power trio that allowed him to capitalize on the post-Nirvana alternative nation he helped create. A musical gene-splice of Hüsker Dü and Cheap Trick, with a crisp, punchy production aesthetic reminiscent of Butch Vig’s work on Nevermind, Sugar’s two LPs, one EP, and B-side collection sold better than any of Mould’s previous work and earned him a new generation of fans. Since that band’s 1996 demise, Mould has made a handful of solo records, including head-scratching detours into electronica, and continues to tour as an elder statesman, finally reincorporating Hüsker material into his sets after years of pretending the songs didn’t exist. By all accounts, including his own, he’s more comfortable in his own skin than he’s ever been.

Besides his musical development, the other major throughline in See a Little Light is Mould’s long, slow acceptance of his place in the gay community. Admitting that he had been a “self-hating homosexual” for most of his life, Mould was a semi-closeted serial monogamist until he reluctantly agreed to be outed in a 1994 SPIN article by novelist Dennis Cooper. He’d never related to the camp, effeminate stereotype of gay men, and impolitically told Cooper, “I’m not a freak.” The magazine’s editors made this a pull quote, much to Mould’s chagrin, and it wasn’t until the late ’90s, when he discovered the “bear” subculture of jeans-and-flannel homosexuals, that he felt truly at home in his sexuality. The last third of the memoir is largely devoted to this transformation, which saw Mould breaking up with a longtime boyfriend, going on a promiscuous tear through the gay clubs of New York City, and starting a revolving dance party called “Blowoff,” at which he DJs to this day in New York, Washington, DC, and San Francisco.

Throughout this period, he was trying to free himself from the “burden of being Bob Mould, the Rock Guitar Guy…. Bob Mould, the Angry Man. Bob Mould, the Miserablist. Bob Mould, the Pessimist. The Smoker. The Bad Ender of Things. The Self-Hating Homosexual. It was time for all of these to leave the stage, hopefully to make room for Bob Mould, the Gay Man.” There was also a detour into one of his lifelong loves, professional wrestling, which he’s defended to incredulous journalists over the years as “Shakespeare with gymnastics.” Writing scripts for World Championship Wrestling, Mould started taking the steroids offered by his colleagues and endured an insanely hectic work-travel schedule that made touring with Hüsker Dü seem leisurely.

Today, Mould finally seems to have found his “peace at the center,” as Quakers would put it, having struck a harmonious balance between rock guitar guy and gay man, sensitive songwriter and wrestling fanatic, even post-punk “bear” and practicing Catholic (he started going to Mass for the first time since his confirmation at the suggestion of a friend). He is one of those rare artists who can safely say that he changed the trajectory of his art form. One hopes that his old bandmates and SST Records overcome their differences at least to the extent that the Hüsker catalogue can receive the deluxe reissue treatment the music so richly deserves. As for a reunion tour, don’t hold your breath. “I’ve left Hüsker Dü in the past,” Mould writes. “I’m not interested in diminishing whatever legacy exists just so people can say, ‘I saw Hüsker Dü.’ If you have an original ticket stub dated 1979–87, you saw Hüsker Dü. If not, you missed out.”

Andrew Hultkrans is the author of Forever Changes (Continuum 331/3, 2003).