CLARICE LISPECTOR had a diamond-hard intelligence, a visionary instinct, and a sense of humor that veered from naïf wonder to wicked comedy. She wrote novels that are fractured, cerebral, fundamentally nonnarrative (unless you count as plot a woman standing in her maid’s room gazing at a closet for nearly two hundred pages). And yet she became quite famous, a national icon of Brazil whose face adorned postage stamps. Her first novel, Near to the Wild Heart, appeared in 1943 and was an immediate and huge sensation, celebrated as the finest Portugese-language achievement yet in, as one critic put it, penetrating “the depths of the psychological complexity of the modern soul.” She struggled to get her subsequent novel published, after marrying a diplomat and moving first to Italy, then Switzerland, then Washington, DC. But her return to Brazil in 1959, after divorcing in order to give herself over to her drive to write, commenced a decade when she was at the absolute peak of Brazilian literary society, considered one of the nation’s all-time greatest novelists, and contributing a weekly column (crónica) to Rio’s leading newspaper. The Brazilian singer Cazuza read Lispector’s novel Água Viva 111 times. Lispector was translated by the poets Giuseppe Ungaretti and Elizabeth Bishop, and in Rio she was a known and recognizable celebrity. A woman once knocked on her door in Copacabana and presented her with a fresh octopus, which she then proceeded to season and cook for Lispector in her own kitchen.

An exhaustive and fascinating biographical account of Lispector’s mysterious existence, Why This World, by Benjamin Moser, was widely reviewed when it came out in 2009, and for a moment, many more people in the US had read about Clarice Lispector than had actually read her work. Now, Moser has overseen new translations of five of Lispector’s nine novels, Near to the Wild Heart, The Passion According to G. H. (1964), Água Viva (1973), The Hour of the Star (1977), and A Breath of Life (1978), which has never before appeared in English. This is a lucky moment. It’s much better to start with Lispector herself, in her own words. That said, readers who encounter the novels will likely be driven to read Moser’s biography as well, in order to know who is behind the curtain of that voice, which is so curiously personal and private, the inner voice of the quietest moment of rumination. “Could it be that what I am writing to you is beyond thought?” she writes in Água Viva. “Reasoning is what it is not. Whoever can stop reasoning—which is terribly difficult—let them come along with me.”

I suspect the reason Lispector’s philosophical fiction has inspired such dramatic devotion is that people feel she is talking to them, about the most basic but complex human experience: consciousness, the alienating strangeness of what it is to be alive. She attempts to capture what it is to think our existence as we are in it—in the “marvelous scandal,” as Lispector puts it, of life. We are not a plain is, but an awareness of this is, which is to say totally cut off from the world by the human capacity to conceive our part in it.

Like Lacan, I blame language for this problem. Probably Lispector would too. But both of them, Lispector and Lacan, would agree it’s our only recourse, and both called upon the capacities of language to an extreme degree, one building a set of psychoanalytic theories based on language, the other flexing language and punctuation in the interest of ephemeral and barely graspable truths, not because she was part of any experimental movement, but out of something more like solitary and desperate need. “This is not a message of ideas that I am transmitting to you,” she declares in Água Viva, “but an instinctive ecstasy of whatever is hidden in nature and that I foretell.” And elsewhere, “The next instant, do I make it? or does it make itself?”

Moser speculates in his biography that her compulsion to write in the way she did relates to her origins in the miserable Ukrainian shtetl where she was born in 1920, her Jewish family’s narrow escape from a wave of pogroms (they fled to Brazil when Lispector was an infant), and, when Lispector was nine years old, the death of her mother by syphilis, contracted when she’d been raped by a Russian soldiers. Lispector had no memory of the Ukraine and rarely, if ever, spoke of that dire history. She was a native speaker of Portuguese and identified completely with Brazilian culture. One could argue that the omission of her origins in her work suggests that meaning lies there. But the compulsion to write, or really any compulsion, can never fully be accounted for by biographical details, whether by inheritance or life experience.

While a biographer’s job is to create an account, construct theories of cause and effect, my concerns lie elsewhere, namely, with those aspects of Lispector’s personality and gifts that were possibly ex nihilo, or with those aspects that, regardless of whether a cause existed and can be traced, simply were. The most rudimentary questions of knowledge and being seemed to weigh upon her in an unrelenting way. One has the sense that she really did get up in the morning and face the void. That this elegant and proper Rio lady wrestled with the question of how the hours pass, whether time is nature or human, and why we are so cut off from God, while running her bath and making coffee in her percolator. She died early of cancer, at the age of fifty-six, in 1977, but left behind an astounding body of work that has no real corollary inside literature or outside it.

“I’M THE VESTAL PRIESTESS of a secret I’ve forgotten,” the narrator of The Passion According to G. H. says. “I know about lots of things I’ve never seen,” Lispector says in her own “dedication” for The Hour of the Star. In that same book, she writes that her task, in telling a story, is “to feel for the invisible in the mud itself.” And, “You can’t tell everything because the everything is a hollow nothing.” The everything is the mud, the nothing that contains the something.

Lispector’s subject, a grasping after the secret kept but forgotten, a kind of noumenal reality, “the invisible in the mud,” is one that most writers don’t even touch on. It’s superspecialized. She goes after essence, life stripped of what is the horizon and almost the whole of literature: the social sphere, family life, the contemporary scene, historical time, and, of course, romantic love. For Lispector, there is only the rubbed-down grain of existence underneath all of that, even as her novels sometimes offer the tenuous webbing of narrative: A woman enters her maid’s room and has an ecstatic breakdown/revelation (The Passion According to G. H.); a poor girl from northeastern Brazil comes to Rio and remains poor, dim-witted, and miserable, while the narrator, a writer, contemplates existence, misery, dim-wittedness (The Hour of the Star); a young woman with unusual gifts of perception contemplates life, her childhood, then marries, contemplates life, her childhood, and, vaguely, a love triangle (Near to the Wild Heart). But some of Lispector’s work has not even the pretense of a plot, like the great Água Viva and the even greater A Breath of Life. In both of those novels, Lispector dispenses with, or rather swerves around, narrative altogether, and gives her main subject—being—to us straight, in the form of aphorisms linked together and floating against a background of only white paper. By some sleight of hand she manages to create a sense of forward motion without offering any kind of character development. She writes about thinking, what it’s like to think, and this task is circular, because thought, while not language, is bounded by words, its only tools for expression. It could be said that this attempt to describe thought is the primary narrative propulsion in all of her novels, with the exception of The Hour of the Star, whose central character, Macabéa, is not introspective. (Some people think this book is her masterpiece. I am not one of them.)

In all of her work, she seems to write in service to neither tradition nor vanguardism. Her prose reads like something closer to philosophy, but it’s not philosophy. She isn’t a scholar. She knows things from sun-bright intuition. What writer is her kindred? It’s surprisingly difficult to find a suitable example. Ingeborg Bachmann comes at the same problem of time, but from a different direction, when she writes in Malina that “today” is a word that “only suicides ought to be allowed to use,” because it has no meaning for other people. Kafka is often mentioned, and Lispector appreciated his work, but their writing seems nothing alike. Kafka is a storyteller, no matter how unusual or abstracted the setting and events. Lispector is not. Kafka’s characters are actors in life, who inhabit the world. Lispector’s are not; they do not go here and there, encounter other people, have convincing spoken exchanges that result in effects on the main character and others.

The oft-mentioned Virginia Woolf is also a misleading comparison, given that Lispector is not stream-of-consciousness. “I want every sentence of this book to be a climax,” she says in A Breath of Life, and even that self-reflexive admission is itself a kind of climax. In terms of midcentury currents and her own contemporaries, I don’t believe Lispector was consciously experimental. There is no Oedipal break being put into play, as with the New Novelists, no Oulipian limitation created in order to unlock something. If anything, there might be a link between her and the great Brazilian artists of her generation, Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape, and Hélio Oiticica. As she says in Água Viva, “I want geometric streaks that cross in the air and form a disharmony that I understand. Pure it.” When she was living in Chevy Chase, Maryland, in the 1950s, playing, or simply being, a housewife, Lispector’s own contribution to the American Christmas tradition of holiday decorations was to cover a pine tree on her front lawn with dangling irregular forms in black, gray, and brown. “For me,” she said, “that’s what Christmas is.”

It’s important not to let cultishness stand in for the experience of her sentences directly, and yet the surreal mythologies of her life, like her wonderfully somber Christmas decorations, are a little too tempting to resist mentioning. Her dog smoked cigarettes and drank alcohol. She once held a dinner party and forgot to serve food. She said organ music was “demonic” but that she wanted her life to be accompanied by it. She wrote an advice column for a Rio paper with tips such as “Act as if your problems don’t exist,” and “No matter how French your perfume is, it’s often the grilled meat that matters.” Friends spoke of her “scandalous” cosmetics application, which grew more extreme after she fell asleep smoking and was burned terribly, and her makeup evolved even further when, in the years directly before she died, she asked her makeup artist to apply “permanent cosmetics” monthly, while she slept. The way she writes of beauty and vanity cohere with this odd detail: “What others get from me is then reflected back onto me, and forms the atmosphere called: ‘I.’” Femininity, after all, is both utterly natural and completely fake, a kind of psychosis, and also the unifying impression a woman makes, the thing that keeps her gathered. And so why not permanent makeup, for the woman who feels she is slipping, in more than one sense?

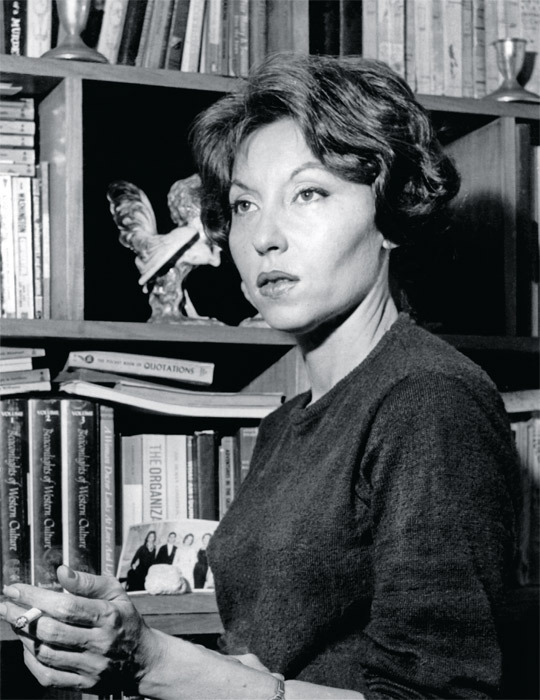

She was indeed beautiful for most of her life, with a face whose astral luminosity reminds me of topaz, her favorite stone. De Chirico painted her portrait, and there is the overhyped quote by Gregory Rabassa, translator of her novel The Apple in the Dark, which everyone repeated when Moser’s biography came out, about her looking like Marlene Dietrich and writing like Virginia Woolf. No one would say that Albert Camus looked like Humphrey Bogart and wrote like André Gide. What Rabassa means is that she pulled off the (unlikely) feat of being viable as both a woman and a writer. And yet I, too (wanting viability as both), have looked at her photos quite a bit. There is one in particular in which the inside of her arm looks so tender-soft that it produces a kind of confusion, a magnetic confusion that tells me I won’t really understand much by looking at her photo, at flesh whose innocent appearance contradicts the mystical tone of even her earliest fiction (she had completed Near to the Wild Heart by the age of twenty-three). My favorite moment in all of her work is a childhood revelation of non-innocence in “Sunday, Before Falling Asleep,” from her crónicas:

This was when she discovered the Ovaltine they served in cafés. Never before had she experienced such luxury in a tall glass, made all the taller because of the froth on the top, the stool high and wobbly, as she sat on top of the world. Everyone was waiting. The first few sips almost made her sick, but she forced herself to empty the glass. The disturbing responsibility of an unfortunate choice; forcing herself to enjoy what must be enjoyed. . . . . There was also the startling suspicion that Ovaltine is good: it is I who am no good.

It is I who am no good. Hélène Cixous wrote famously of the Ovaltine moment, and it was through her writings that I originally found Clarice Lispector. Cixous wrote copiously on her work, and even took Lispector’s reputation as “the sphinx” as a cosmetics tip, and made a habit of appearing publicly in full Egyptian eyeliner. Many of Cixous’s writings on Lispector were actually pedagogical lectures given in the early 1980s at Paris VIII, lectures whose effect in transcription is as magisterial as the eyeliner. I would have been better off reading Lispector directly, rather than in conjunction with the claims about her made by Cixous, whose own tone didn’t wear off for me until I had occasion to pore over these new editions of Lispector’s work.

THE NEW TRANSLATIONS ARE MEANT to be more faithful preservations of Lispector’s intentional roughness and idiosyncrasies. She had a creative way with punctuation, and once wrote a novel that begins with a comma and ends with a colon (and even this does not seem self-consciously experimental, but rather the assignation of heavy-duty work to frail grammar). Not a reader of Portuguese, I cannot assess the accuracy of the new translations. But they do indeed seem different from the earlier ones, and each new edition is published with an introduction that attempts to frame the work of Lispector in a less hermetic, less febrile light.

“In truth she had always been two, the one that had a slight idea that she was and the one that actually was, profoundly,” she wrote in Near to the Wild Heart, which is filled with crystalline insights and also seems to hold in it a code for the way in which her work would eventually evolve. Its protagonist, Joana, apparently autobiographical, commits to married life just as she is also giving herself over to this second incarnation, the one who “is, profoundly,” who gives herself over to herself, which is to say, to introspection. The original translation, by Giovanni Pontiero, is not radically different from the new one, by Alison Entrekin, but in small ways, the cumulative effect of the book is much improved.

Moser himself retranslated Hour of the Star, Lispector’s funniest work by far. The protagonist, Macabéa, a wretched waif who comes to Rio from the slums of Recife, in northeastern Brazil (where Lispector herself spent her childhood), fails to find love or break free of ruinous poverty. A virgin who lives on hot dogs and Coca-Cola, she dreams of a house with a water well and wonders out loud, “Do you know if you can buy a hole?” (It may be only a coincidence, but maca in Fijian means “empty.”) She visits a doctor who recommends beer and spaghetti as a solution to her problems. Meets a whore turned madam and fortune-teller who “sentences her to life,” and is afterward run over by a Mercedes. In this book of exceedingly whittled and spare prose, which was also originally translated by Pontiero, each word counts. This line, from Moser’s new translation, “You do yourself in if you don’t do yourself up,” was translated by Pontiero as “Without a touch of glamour, you don’t stand a chance.” They mean the same thing but don’t have the same aural effect (especially if we are led to think of Lispector herself, who did not merely go for a “touch of glamour,” but indeed did herself up).

If I cannot assess the translations themselves, I know that the new rendition, by Idra Novey, of The Passion According to G. H. should be regarded as an event, based on the previous translator Ronald W. Sousa’s admission in his own 1988 introduction that he didn’t consider it a novel, and that his translation was “more expository in tone” than the original. Novey, by contrast, writes in her afterword about her own deep cathexis to the book. This new edition also includes an introduction by Caetano Veloso (probably the most famous person in all of Brazil, which perhaps gives him the leeway to make the absurd suggestion that Spinoza wrote the Ethics in Portuguese).

Lispector’s most unrelenting and serious work, The Passion is a first-person account of a woman who passes into a state of intense exaltation—bathes in the Judeo-mystical Tzimtzum of God’s absence, but also partakes in the Catholic transubstantiation of God’s presence, as if tasting the host—when she eats a cockroach. This is often described as “shocking,” but it isn’t, really. The severe philosophical austerity of her “passion” is offset by the bourgeois existence of G. H., who enters her maid’s vacated room and begins this incipient process of spiritual transformation when her eyes alight on the roach. There’s a curious racial overtone, a white woman and her absent black maid, a white room, a black cockroach, which she describes as looking like a “dying mulatto woman.” Class is also significant: Lispector was obsessed with her maids and wrote about them in great detail in her newspaper columns, and in picturing this haute-bourgeois character delivered into blessedness in a maid’s room, I can’t help but see an elegant woman with manicured nails biting into the creamy ooze of divine substance, the roach, as if into a bonbon. And yet there is nothing kitsch about this book. It is a precise portrait of an encounter with the secret to life: the nothing that subtends everything, the mud.

A Breath of Life, Lispector’s very last book, edited posthumously by her loyal friend Olga Borelli, a former nun who was possibly in love with Lispector, is the final installation, after Água Viva (which was also put together by Borelli from fragments and scraps), in a process that Lispector herself described, in regard to revising Água Viva, as a “drying out.” These two books are subjectless treatises on thought, being, mode. A Breath of Life is structured as a feverish dialogue between interlocutors who are really just vehicles for opposing epiphanies on life, and on the death that Lispector knew was imminent—not in a ghastly and physical way but as an inevitable encounter with nothingness. These epiphanies are delivered one after the other in a book-length relay, a final and magnificent apotheosis of Lispectorisms. I could quote every line and still not do the book justice.

“One’s incommunicability with oneself is the great vortex of the nothing.”

“When it’s happening living escapes me. I am a memory of myself.”

“Life is very quick, when you see it, you’ve reached the end. And to top it off we’re required to love God.”

“There must be a way not to die, it’s just that I haven’t discovered it.”

“I can only accept that I got lost if I imagine that someone is holding my hand,” Lispector writes in The Passion. And also in that book: “Holding someone’s hand was always my idea of joy.”

This kind of unabashed plea—to hold someone’s hand—seems almost surprising amid all of the pondering on emptiness, which creates, in contrast, the impression of someone unreachable, imperious and solitary, and she indeed had that reputation. But at the end of her life she was not alone, and had a great friend in Olga Borelli, perhaps her most ardent admirer. Posthumously, Borelli put together A Breath of Life by sorting through Lispector’s notes, which, she said, still smelled of the author’s lipstick.

“It’s a disgrace to be born in order to die without knowing when or where,” she’d written in Água Viva. “I’m going to stay very happy, you hear?”

As if in answer to the simplest yearning in her fiction, as she was lost to the world—ours, and her own—she did not have to imagine someone was holding her hand. At the moment of Clarice Lispector’s death, her hand was in Borelli’s.

Rachel Kushner is the author of The Flamethrowers, forthcoming from Scribner in April 2013, and Telex from Cuba (2008).