Cyrus Grace Dunham’s memoir, A Year Without a Name, was written in real time over the course of two years, a name change, and what popularly constitutes a gender transition. The book emerged from a compulsive writing practice, an experiment in self-actualization that saw Dunham writing toward the version of himself he’d always fantasised about embodying. In spare language, Dunham writes through changing relationships, everyday setbacks, and resolutions.

Dunham is acutely aware of what it’s like to be made a character of; one of the primary concerns of his book is how to write from life without spinning people into fictions. While few readers are in positions to judge whether he succeeds in this mission, the anxiety of writing undergirds his musings on identity, persona, and authenticity. Dunham renders his discomforts with being at once a writer, a sister, a child, and a body hyper-legible without declaring them heroically vanquished.

What resolves is a diaristic cross-section, almost picaresque, of a person in flux: A trickster character traverses the globe, always encountering new people to devote life chapters to. Ultimately, Dunham takes subjecthood as his subject, and the flitting era ends. But what escapes the purview of subjecthood? Activities like driving a convertible, letting hair fall across his eyes just so, and tumbling in and out of love are considered in serious if not equal measure. As in a certain meme template, Dunham extends a hand to every fancy he meets, wondering, “Is this an ‘I?’” We talked about trickery, transphobia, and making writing accessible.

You present different attitudes about writing in the book: anxiety that your words may be an “unnecessary contribution,” and also how writing has always been “inherently optimistic” for you. Can you tell me more about these positions?

Over the course of my transition and the time leading up to it, the book and the writing became such a proxy for how I was feeling about myself in the world. So, if it was a good day where I felt on track and grounded and connected to myself, I would feel this deep joy and hopefulness about the writing; if I was feeling stuck and low, writing would feel so, so, futile.

I do hold a lot of skepticism and cynicism about writing and the way that language can be such a dominant and violent force, but I also feel some sort of simple or wishful naïveté, like, if you really try to be honest, you can get closer to people. And not everybody thinks that. I’m able to suspend judgment enough to just sit down and be like, I just want to try to be authentic. I don’t know if that would hold up under a lot of examination, but it is a feeling that I have.

And with this authenticity comes taboo, right? I’m thinking of how you describe jealousy that your friend started hormone therapy before you did, the “thought circuit” of self-doubt regarding surgery.

Right. Of course, the final book has an element of curation, of artifice, but it was important to me to expose parts of myself I wasn’t proud of, and how unseemly emotions like envy and anger and disgust and jealousy would be part of something that’s supposed to be as self-oriented as a gender transition. And even with my closest friends, I often find myself thinking that everybody’s mind is this demented, berserk universe of pain and longing and desire. All the good stuff is wrapped up with the bad stuff—and good and bad aren’t even real categories! We’re all pure and we’re all evil.

Speaking of, your persona in the book is sort of a trickster or chameleon—your mother says you have a “lying bone.” Knowing that some people could so easily in bad faith use that to invalidate your story and trans people’s experiences, this seems to me a pretty brave move.

Well, one of the transphobic fixations in our culture is how to tell if someone is “actually” trans, how to know if trans people are both lying to themselves and lying to everyone else. And obviously, the history of anti–cross dressing laws and laws that criminalize nonconformity is always about this fear that the trans person will trick the unsuspecting citizen with their performance.

Even in liberal discourse, we see this panic among parents that there’s this trend of young, white, highly educated women waking up one day and suddenly stating that they’re not women and wanting to transition, like this is a contagious illness that’s spreading. The idea being that womanhood is the truth and then the gender deviance is the trick. So, there’s a necessity among trans people to convince the world that we’re real.

And in the book I was just like, “Maybe I am tricking people, and maybe that is . . . my gender.” You know? Because with biological gender, the truth that we’re supposed to be proving we are . . . is also a lie.

Right, gender always involves trickery of some sort. You also articulate devotion as one of the closest things you’ve ever known to a stable gender, and novelty as a “long-lasting short-term coping system.” In moments like these, where you convey lofty ideas plainly, how were you thinking about style and accessibility?

I think if accessibility and readability weren’t important to me I wouldn’t have written a book like this. I can write in a lot of modalities, and that’s also part of being a trickster. I’m a really good mimic. I’ve always been able to read theory and then mimic theory, read journalism and then mimic journalism. My partner is a poet and one of our favorite games is to read books of poetry, like, beautiful, amazing poetry that I could truly never dream of living up to—but then we go on walks and I just babble, babble, babble, you know, do my own imitations of the poets.

You’re like Elizabeth Hardwick! She was often better than the writers she imitated.

I’m like a little writer-parrot! And also when Rosie, my partner, gets stuck, sometimes I’ll just write poems as them, and be like,“Here’s a poem!”

Sounds infuriating for Rosie.

No, I mean, they do all these things I could never do, you know? But it’s just so freeing for me, so incredibly fun to imitate people’s writing. And it comes from a place of a lot of love and admiration. But with my book I wanted to write without imitating anyone, so I tried to write as close to the way I talk as I can. I think a lot of times I write as if I’m going to be giving a speech or something.

What do you mean by that?

I pretty much read everything out loud after I write it. And I wanted this book to feel equivalent to sitting on my bed with a close friend and just, really slowly, trying to tell them as close to what I actually feel or think about something. And, of course, I know that even vulnerability and intimacy are a performance, too, but maybe this was the performance that I chose to do with this project.

For sure. We should also talk about your convertible.

My convertible is sitting right outside the window as we speak!

It’s funny to think about your desire to own and drive a convertible, this masculine signifier that is very wedded to stereotype, and almost kitschy, and hold that up to the subtleties you name that strike at something very real in the history of queer signaling, like, how to stand and how to take off a shirt in a coded way.

Well, I just absolutely love and cherish my convertible. I haven’t been able to tell if the reason I wanted the convertible was because of the way that it feels masculine or because it feels so good to be out in the world and zooming down the road and not having a boundary around myself. I already tend toward claustrophobia in my body pretty intensely and it’s such a relieving and wonderful feeling to just feel the air around your face and not feel separate from everyone and everything.

Like, your body is the car.

Exactly. I really felt that at times. But what you said about gestures, that’s so important to me. Like, I don’t even know what “a man” is, right? Whatever a white man is in our culture is not something I really ever wanted to be. But there were these ways of being embodied that I longed for.

I have a close friend named Sarah who’s a choreographer and we had lunch a few weeks ago and talked about how every body has its own innate choreography, but that norms of gender or ability make us repress and subdue our bodies’ natural gestures and forms of expression.

And so much of my adolescence was about trying to overcome my own embodiment. Like, forcing myself to walk like a girl—whatever that means—and then letting myself stomp around with this sloppy, wide gait when I was alone. And people don’t like manspreading that much, but, for whatever reason, the most comfortable way for me to sit was always to slouch over with my legs spread super wide like some weird dude. So, I think reconnecting with what one might call a more authentic version of my gender wasn’t necessarily about being a man, as much as it was about letting that part of myself speak in some way, reconnecting to that through fantasy.

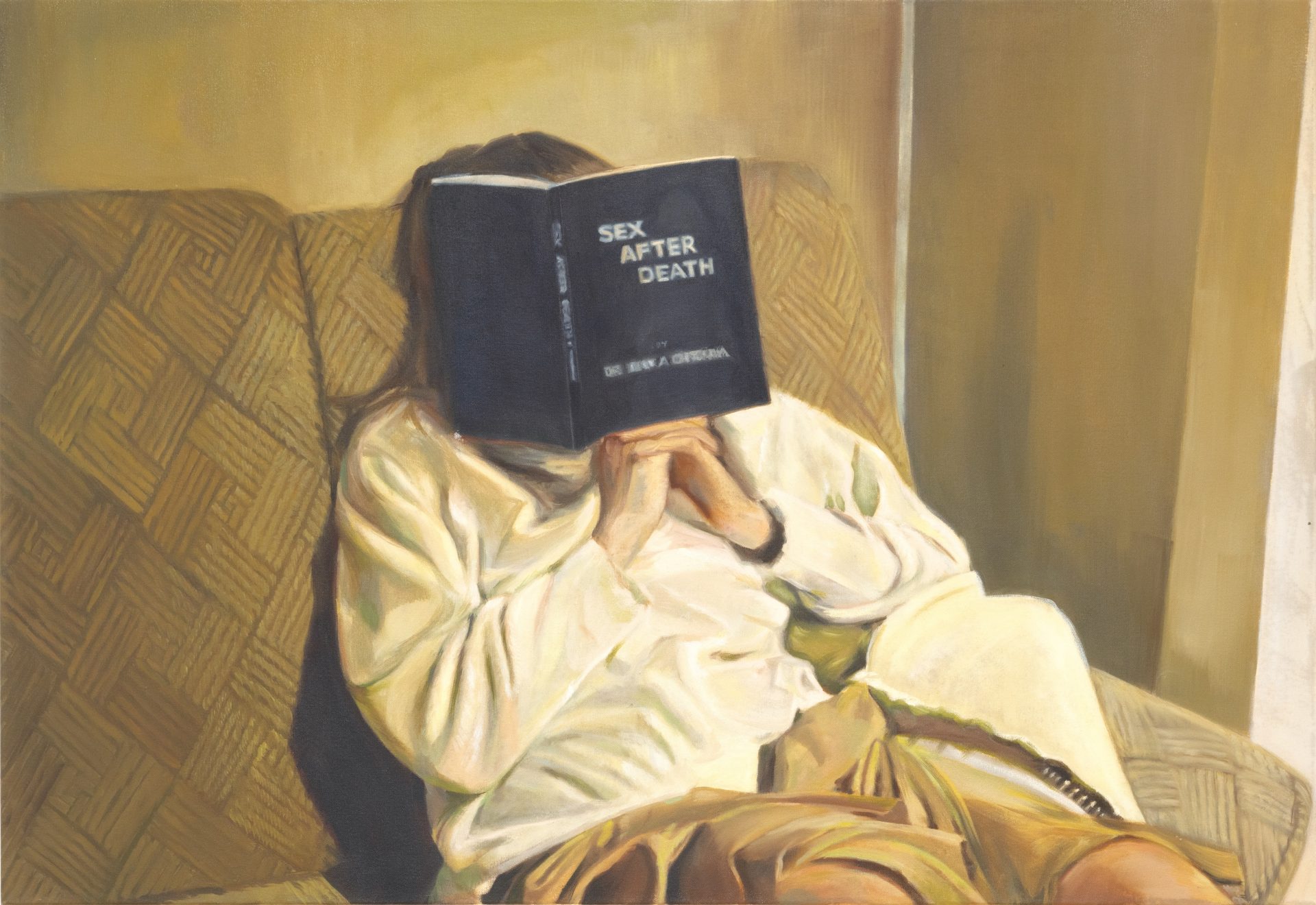

And personal fantasy is a big part of the book, but it’s officially a memoir.

You know, at the beginning I wasn’t sure it was. I was like,“Should this be memoir? Is this fiction? Can I write it as myself but call it fiction? So many people seem to do that.” And then I thought, you know, it’s really scary to think about writing memoir, and there’s something humiliating about being a twenty-seven-year-old who’s sharing something categorized as a memoir, because the genre tends to communicate this grandiosity of the self. But I decided that might be really productive for me, because I was trying to get to the most raw parts of myself.

Can you talk about the choice to omit your partner from the narrative in the final chapter, when you’re getting surgery and in recovery?

The person I’m with at the end of the book is also a writer, so our conversations about our relationship often end up in places that have to do with story and omission and some of the same themes that I’m working through in the book. And it felt relevant that I had omitted them, because it showed me how I wanted the book to end, which was with me not needing this particular type of witnessing.

And what is that type of witnessing?

I think I wanted the book to end with me being so transformed that I didn’t need a lover to affirm my existence. And in some ways that ended up being true, and in other ways that didn’t end up being true.

Right. But then you explain the omission in the afterword, so it’s not really an omission.

Yeah, I was like, “Whatever way I want the book to end is obviously how it can’t end.”

Lizzy Harding is a writer from Portland, Oregon. She lives in New York and works at Bookforum.