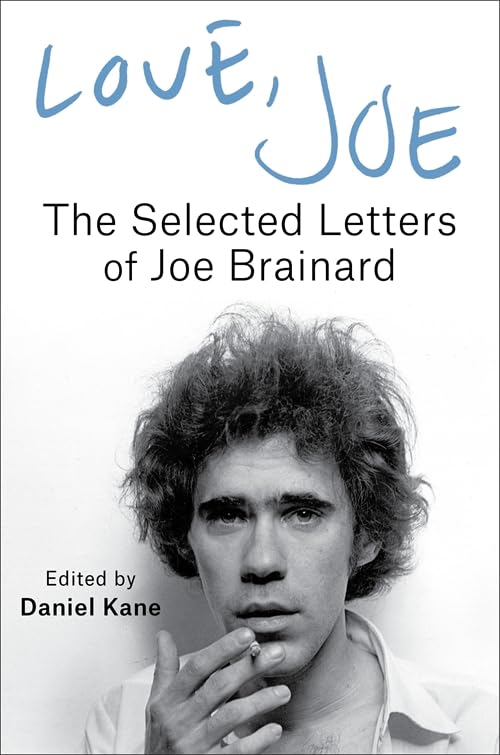

EVEN A CURSORY GLANCE at the life of Joe Brainard reveals him to have been something of a genius of friendship. Since the artist and writer died of AIDS-induced pneumonia in 1994 at the age of fifty-three, his legacy has been steadfastly tended to by a band of his contemporaries, who jump at the chance to rhapsodize at length not just about the man’s achievements but also his gentleness and unpretentiousness. Foremost among these evangelists is the poet Ron Padgett, whose close bond with Brainard began when the two were high school classmates in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in the 1950s. In the past two decades, Padgett has published the unabashedly affectionate memoir Joe, edited an authoritative anthology of Brainard’s writing, and served as the narrator of a short film about his friend, directed by the documentarian Matt Wolf. It’s easy to understand the urge to advocate for Brainard’s place in history. A staunchly idiosyncratic devotee of small-scale work, he was well-reviewed during his lifetime without ever becoming a brand name in the art world, partly due to his lack of skill and interest in the business side of his profession. One imagines that, by posthumously shepherding him into the spotlight, his friends are trying to reconcile a long-held desire to see him succeed with their respect for his humility.

One of the most charming things we glean from Love, Joe, a collection of Brainard’s letters edited by the academic Daniel Kane, is the sense that the artist could afford to be less fame-obsessed precisely because he was so consumed and fulfilled by his social life. At one point, he brags to the poet Anne Waldman that he has “good friends running out of my ears.” But he was never complacent about this abundance: he was a chronic people pleaser—a persona that may have resulted from his childhood hunger to be liked, but one that he learned to inhabit with gusto and self-assurance. Throughout his career, he designed magazines and book covers for poet friends, including Padgett, Waldman, and John Ashbery, and he sometimes conceived his artworks as gifts to his many acquaintances. The occasional, improvisational quality of much of his work was at odds with the gloomy monumentality of the Abstract Expressionists, who dominated the American art scene of his young adulthood. The voice we encounter throughout Love, Joe is much more comfortable with meandering chitchat than with pontification on cultural matters. When Brainard does get around to nailing down an aesthetic principle, he favors a modest, antiheroic understanding of his vocation: “Art is not God,” he insists in one letter to the poet Bill Berkson. “Art is not that serious.”

Over the course of a prolific career that never yielded a recognizable visual signature, Brainard’s allergy to grandeur and self-aggrandizement emerged as a loose through line. It’s not that Brainard didn’t have a robust ego. Like most artists with high standards, he wanted to impress his audience; he even dreamed of mastering oil painting, a medium that might have lent his oeuvre a greater semblance of gravitas. But he always seemed more comfortable in less prestigious forms, like assemblages and collages, which gave him the freedom to preserve disposable objects—matchbooks, cigarette butts, playing cards, costume jewelry, receipts—and highlight their material strangeness through sly, ineffably poignant juxtapositions. There are no bold or provocative statements in these works. For Brainard, whimsy, nostalgia, and cartoonish humor were sufficiently worthy pursuits, requiring no conceptual justification. Most of his drawings and paintings—whose central figures include animals, flowers, and the beloved comic-strip character Nancy—have the same light, frothy tone, their playfulness anchored by his subtly sophisticated use of color and line. And when it came to his writing, he devised forms that brought as much focus to miniscule, seemingly throwaway details as to major, life-altering experiences. In what is now probably his most well-known work, the 1970 experimental memoir I Remember, the titular phrase serves as the opening refrain of each of the book’s many hundreds of sentences and short paragraphs. This incantatory repetition allows Brainard to accrete a wide range of sense memories—first erections, popular hairstyles of his youth, the feel of wrinkled T-shirts—while insisting on their equal standing in his mind. Though the book never strains for psychological insight or a totalizing worldview, its mix of naive wonder and deathbed reflection feels like its own kind of wisdom.

There are times when a dip into the archives can expose an aspect of an artist’s personality not apparent in their official oeuvre: one thinks of Kafka’s love letters to Milena Jesenská, which are so much more hot-blooded than his enigmatic, eerily clinical fiction, and Elizabeth Bishop’s trove of correspondences, which illuminate the private torments she buried deep beneath the surface of her poems. In contrast, Brainard’s letters read like a natural extension of his creative ethos; regardless of what genre or mode he was working in, he always seemed to be addressing his audience as though it were his own tightknit inner circle, and his epistolary style has the same “off-ness” he once told the Padgetts that he hoped to achieve in his art. Like I Remember,the letters evince the freewheeling spirit of someone who finds as much interest in all-consuming passions as he does in the detritus of quotidian existence. In Love, Joe,confessions of romantic anxiety and professional uncertainty often veer, without transition, into stray bits of gossip and comments on everything from suntanning to toenail fungus to an encounter with the movie star Anthony Perkins. Beguilingly epigrammatic, crystalline assertions of self-knowledge (“If only I was as smart as I really am”) butt up against charmingly sloppy syntax (“This is another one of those really not a letter at all”) and endearingly juvenile diction (“fuckadoo,” “yes-yes,” and his favorite erotic exclamation, “slurp”).

These latter two elements have their roots in Brainard’s linguistic shortcomings, of which he was aware (“I have an odd history with words,” he confides in one letter). As Padgett recalls in Joe, the young Brainard talked with a stutter, which led many of his teachers and classmates to regard him as intellectually deficient. Whereas his visual skills were undeniable from an early age, writing was a gift he stumbled on because of the milieu he settled into; after he moved to New York City in the ’60s, his closest friends tended to be writers, and he sought to share their chosen art form with them, shrugging off the fact that his vocabulary was relatively limited and his spelling and grammar often imperfect. In his embrace of casual American vernacular, Brainard bore the influence of the New York School pioneers with whom he was acquainted, including Frank O’Hara and James Schuyler, but unlike those older writers, he was rarely allusive, cerebral, or coolly ironic. He explains in one of his letters to the Padgetts, “I guess it is alright to be insincere but it seems to me that you ought to be sincere first.”

Despite the delight he took in open-hearted exchanges of confidences, Brainard also enjoyed the kind of writing that has nothing terribly revelatory to disclose, that seems intended simply to fill up a small space in the reader’s day. At one point in Love, Joe, he compliments Schuyler on composing “such nice letters even when you have nothing in particular to say”; at another, he tells the love of his life, Kenward Elmslie, “I hope you will consider it a compliment that I would never write such a boring letter to anyone but you.” Letter-writing was a way for Brainard to pass the time with loved ones. Throughout the book, he implores his readers to reply as soon as possible and advises them not to labor over their responses, as if their mere, unadorned presence on the page were enough to satisfy his appetite for companionship. This magnanimous, come-as-you-are attitude is an essential part of his charisma; Brainard clearly valued wit and wordplay, but he wasn’t needy for entertainment. He mastered one of the trickiest of social skills: securing one’s place in people’s lives without imposing oneself on them. That’s a rare quality in a field that tends to breed narcissism, and this may explain why multiple friends have described him as a saint.

Famously genial in person (Ashbery called him “one of the nicest artists I have ever known”), Brainard seldom succumbs to rage or anguish, even in letters to his closest friends. Love, Joe’s tonal equanimity—a thread that unites letters to almost two dozen recipients over the course of several decades—can give off a sense of nothing much being at stake, making some passages feel unilluminating at best, tedious at worst. (This is perhaps an inevitable problem with collections of writing never intended for publication.) But it also means that when signs of anxiety or unhappiness do appear, they leave a deep impression. When Brainard alludes to more unpleasant emotions, he typically does so with an understatement that runs counter to his loquacious manner. Mention of a tragic death is almost callously brief; his years of dependency on speed (a drug he used to spur his creative productivity) and his HIV diagnosis in 1989 are handled with an evasiveness that invites reading between the lines; and very little light is shed on his decision, in the late ’70s, to leave the art world behind and focus on reading and hanging out with friends.

The book is most compelling when it peeks behind the veil of his default niceness—moments that emerge, strikingly, more often in Brainard’s correspondences with gay friends. The latter half of Love, Joe is electrified by glimpses of his romantic relationships and sexual dalliances, and because Kane has chosen not to sequence the book strictly chronologically but has instead arranged the letters by recipient, these particularly intimate missives register as a sudden rush of voyeuristic pleasure. First up in this section are letters addressed to Elmslie, a poet and librettist from a highly moneyed background who provided the never gainfully employed Brainard with the financial stability he needed, and with whom he shared a decades-long partnership that weathered challenging periods of separation and polyamory. Here we find Brainard beside himself—with lust, devotion, jealousy, and primal feelings of resentment that seem to startle even him. “You’ve managed over the past few years to make me feel like a frumpy shit,” he sneers in one especially caustic message. “Your lack of compassion staggers me.”

As he approached middle age, his flirtations with various paramours were considerably more easygoing, and reveal an erotic imagination worthy of James Joyce: in his messages to the biographer Brad Gooch, he revels in repeating the evocative phrase “the creaming of jeans”; to the actor Keith McDermott, with whom he developed a more serious connection, he sends hilariously smutty descriptions of himself masturbating with bananas and zucchini. An extra layer of charm is added by the selection of goofy, casually impressive drawings that Kane has included, reminders that a Brainard letter is a fundamentally visual experience—from the artwork that invades his pages to the urgency transmitted by his all-caps penmanship.

Based on my love of Joe—an extraordinary testament to the thrills and limitations of emotional intimacy between gay and straight men in an era when widespread acceptance of homosexuality still seemed like a pipe dream—I assumed I’d be most moved by Brainard’s letters to Ron Padgett. But in a book filled with recognizable names, I was much more drawn to correspondences with a relatively unknown figure, Robert Butts, a fan from the suburbs of Los Angeles who began buying Brainard’s work early in the artist’s career and later donated his collection to the University of California, San Diego. Little is known about Butts, partly because he had no significant professional ties to art or literature, but his presence in these pages introduces an old queer archetype very different from the role of urban bon vivant that Brainard embodied: from what can be inferred from the letters, Butts was a socially awkward introvert, someone in search of a mentor who could coach him on how to live as a homosexual. Brainard befriends Butts without much hand-wringing or hesitation, gently bringing up the subject of Butts’s apparent infatuation with him, normalizing his experience as an adult gay virgin, and nudging him to come out of his shell (“an encounter with another person is an exciting experience in itself, just for having ‘done’ it”). Brainard’s encouragement is free of ideologically driven advice, befitting a man who seemed to keep a distance from the culture wars and political discourses of his era. As could be said of the whole of Love, Joe, these letters radiate the warmth of a companion who, once he committed himself to you, was in it for the long haul. This collection functions as a guidebook on how to be lovable, a lesson in the importance of withholding judgment, being abidingly present, and seeing one’s friends—minutely, fondly, unblinkingly—for all that they are.

Andrew Chan is a writer and editor living in New York. He is the author of Why Mariah Carey Matters (University of Texas Press, 2023).