Admirers of the great Howard Jacobson have made a parlor game of accounting for why he’s not been recognized as one of the most absorbing and intelligent Anglophone novelists. It beggars the imagination to think that the man who wrote The Mighty Walzer (1999) has won no major accolade in award-mad Britain and has barely appeared in print in the States. So, some possibilities: He’s been written off as a mere comic novelist, and a smut-peddling comedian at that; he’s impolitely Jewish, his sentences lousy with Yiddish; and he laments the state of British culture in a weekly Independent column.

But nothing, I suspect, has been as damaging to Jacobson as we admirers ourselves. We insist on recommending him in the least helpful of ways: Either he is the British Philip Roth or he is the Jewish Zadie Smith. But Jacobson is Jacobson—and neither Roth nor Smith, despite the superficial resemblances. Each of these writers belies generic notions of minority and, more important, assimilation. Assimilation, each suggests, is something that happens between cultures, not from one culture to another. Roth and Jacobson certainly share an interest in the conflicts of conflicted characters caught in this process. Their fiction attentively reveals what divides Mancunian Jews such as Oliver Walzer and Max Glickman (narrator of Jacobson’s magisterial ninth novel, Kalooki Nights) from their cousins in Newark. (Some issues, of course, are just semantic: What Glickman’s mother calls kalooki, Roth’s matriarchs call canasta.)

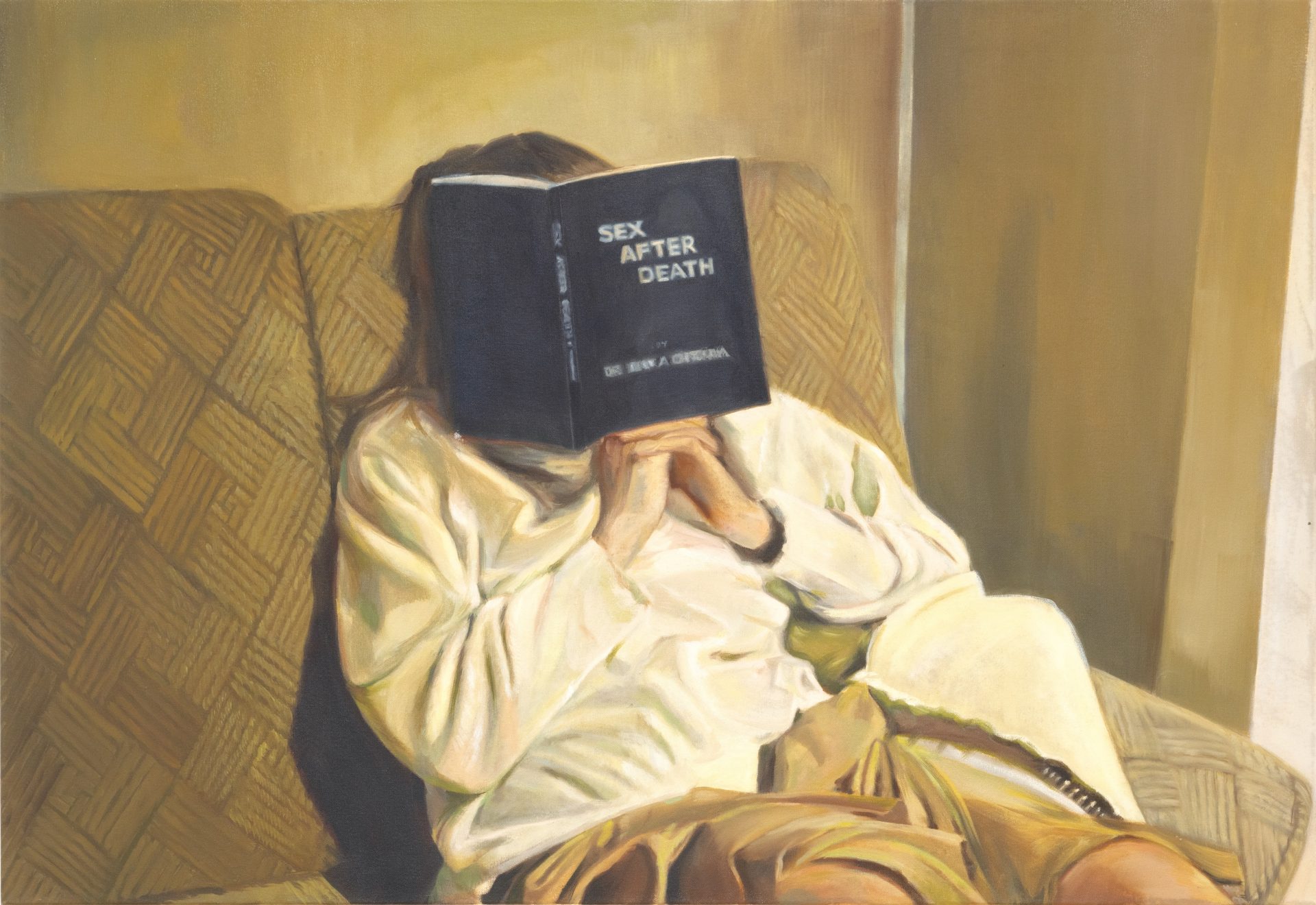

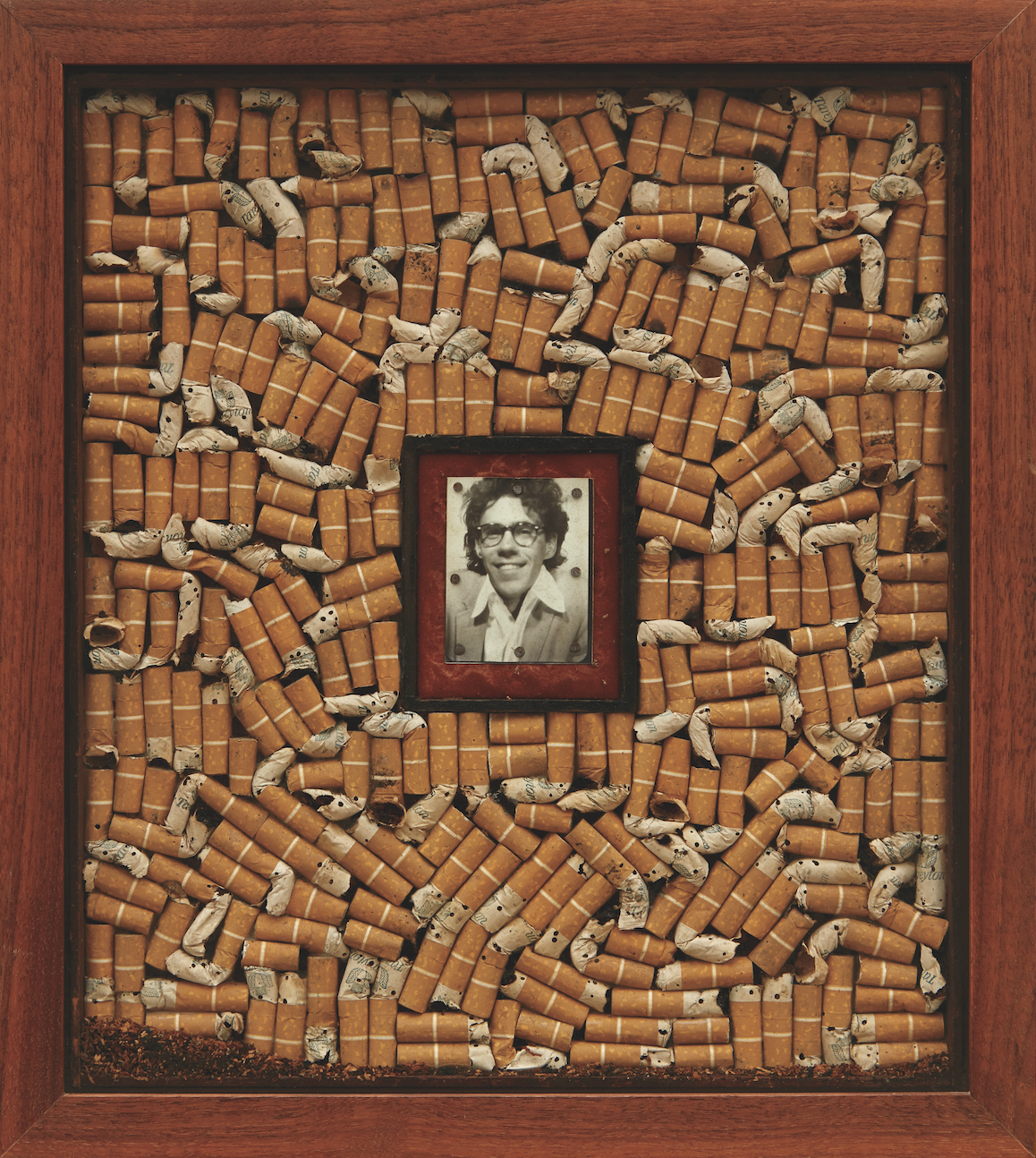

Glickman is an aging and rather unsuccessful cartoonist. His masterpiece, a cartoon history of the Jews called Five Thousand Years of Bitterness, was published to no acclaim—autobiographical shades, perhaps—and he has been reduced to copying gay cartoon pornography from Finland for a pirate publisher. (He fails only at reproducing the “straining bulge” in the characters’ pants. “Jewish men,” he explains, “wear loose, comfortable trousers with a double pleat.”) Glickman’s roots, like Jacobson’s, are in a suburban Manchester ghetto called Crumpsall Park, but he now lives in London. He has been married three times, the first two to hilariously interchangeable shiksas named Chloë and Zoë and the last to a depressive Jewess named Alÿs. (“What does it say about me that the only people with whom I am able to enjoy intimacy must have diaereses or umlauts in their names?”)

Glickman inadvertently tells his own story by way of a biography of his childhood friend Manny Washinsky, a frumkie—in Glickman’s secular atheist family, a pejorative epithet for an Orthodox Jew—from the end of his street. Washinsky, pale and weak and particularly susceptible to Glickman’s caricaturing imagination, murdered his own parents in the ’70s. Two producers of lurid television docudramas have hired the cartoonist to write a treatment of the case. Kalooki Nights is structured around his attempts to draw out Washinsky’s motive for the murders. At his trial, Washinsky invoked the story of Georg Renno, an SS doctor responsible for the gas chambers at a camp. “Turning the tap on,” said Renno upon his arrest, “was no big deal.” “It was in order to verify this claim that Manny had turned the tap on while his parents were asleep. Renno was wrong, he said in his statement. Turning the tap on was a big deal.”

The actual plot, insofar as there is one, is almost irrelevant to Jacobson’s aim, which is to describe with painful exactitude how it feels to sort out one’s relationship to the demands of two cultures; Glickman calls this “the emotional politics of being Jewish.” The urgent question of such a politics is how to maintain a necessary sense of separation without being too noticeably separate: “Why are all the Jews up here,” Glickman asks when he visits his mother in Crumpsall Park, “either make-believe goyim or Hassidim in fancy dress? In hiding, or not in hiding enough.” Jacobson’s skill lies in showing how Glickman uses precedents inside English culture to accommodate his outsider perspective. English class structure aggravates Glickman’s sense of Judaism as a natural aristocracy: Both are beyond the unseemly fray, although aristocrats are above it and Jews below it—Glickman is a vulgar caricaturist the way Disraeli was a dandy. Both transform victimization into sarcastic, self-styled exoticism.

Jacobson’s Jews thus see themselves as what Disraeli called “trustees of tradition”: an ambivalently conservative element, halfhearted moralists pitted against the anything-goes lifestyle of their goyish neighbors. But, they also wonder, what if our otherworldliness is not our own? What if, as Nietzsche claimed, the genius of Jews is simply the ability to spin ostracism as chosenness?

What makes Jacobson’s protagonist so complex and engaging is that he is only successfully himself insofar as this conflict drives him almost crazy. “My father,” Glickman writes, “believed that Jews bore a special responsibility not to be special, so he hated Israel for existing, then hated it for not existing well.” Such an anguished illogic helps him ultimately achieve a kind of fighter’s peace—perhaps best represented by the phenomenon of the Holocaust joke: “You can see why the goyim resorted to the gas chambers. They wanted us to leave their heads alone. But here we still were, still ratcheting up our consciences. Jews refining their Jewishness in the act of refusing to be Jewish.” But if you can’t manage to construct a viable identity from such continuity-in-refusal, you end up killing your parents.

This tragic take is, of course, hilarious as well: Jacobson is funnier, sentence for sentence, than early Roth and Joseph Heller put together. All comparisons aside, however, the simple point is that Jacobson deserves to be read, and read widely, on his own terms. If there is any justice in the world—as Glickman well knows that there isn’t—Kalooki Nights will at long last show an American audience why.

Gideon Lewis-Kraus was a finalist for the NBCC’s 2007 Nona Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing.