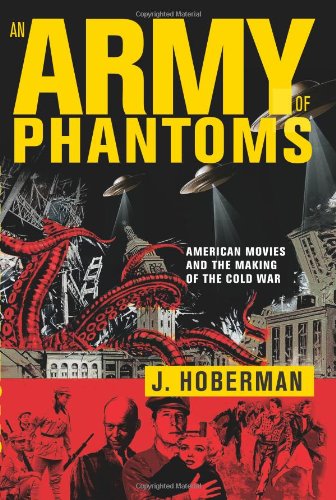

It’s always good to revisit the cold war to remind yourself that, despite an orgy of supporting evidence, you’re not living through the most fucked-up period in American history. As J. Hoberman’s factually dense, swiftly narrated history of Hollywood’s symbiosis with the atomic-age body politic makes clear, the cold war was, pace our current moment, the third great battle over the nation’s identity and purpose, trailing only the Revolutionary and Civil Wars in significance.

An Army of Phantoms is, like the second Star Wars trilogy, a prequel, in this case to Hoberman’s 2003 The Dream Life: Movies, Media, and the Mythology of the Sixties. And during the postwar decade of 1946–56, the scope of this new volume, the phantoms were legion: atomic radiation, Communist spies, space aliens, brainwashing, the Mafia, juvenile delinquents. In the wake of World War II, fear of the unknown gripped the American people, a fear that could resolve to Manichaean clarity (“Better dead than Red!”) or ideological murkiness and paranoia. The enemy was always Them!—when in truth it was also Us.

Hoberman bookends his story with analyses of two films, each concerned with radically different notions of God, mass media, and America’s sense of self. The first, The Next Voice You Hear (1950), directed by William Wellman, is a bizarre Hallmark card of a film, premised on the idea that God decides to take to the airwaves (radio, not television, in Hollywood’s anxious wish fulfillment) for six nights and broadcast His message to the American people. Starring the future Nancy Reagan as a dutiful housewife, the film seeks to comfort an uneasy public, unite the country into one big studio audience, and uphold family values. The audible voice of God is not the film’s only departure from reality, as Hoberman notes:

No one refers to the atomic bomb, let alone the recent loss of America’s nuclear monopoly. The Russians are furtively mentioned (but not China). The words “Communism” and “fascism” are never whispered; neither is the name “Jesus.” Thus, The Next Voice You Hear is set in a fantastic parallel universe that rigorously works to exclude, conceal, or deny that which it might actually be about. Let’s call that imaginary world the Movies.

In the intervening pages, as the most committed Hollywood Communists “conceal and deny” beneath the Capitol Hill klieg lights of the bullying House Un-American Activities Committee huac hearings, the Dream Life becomes both activist and allegorical, with Hollywood studios churning out hyper-patriotic cavalry westerns that conflate “redskins” with Reds, baldly propagandistic fare like I Was a Communist for the FBI (1951), and alien-invasion flicks that could be about either Communist infiltration or creeping conformity. There were more ambiguous offerings as well: wide-screen Roman and biblical epics that allowed both conservative Christians and godless Commies to feel the solidarity of persecution, juvenile-delinquent films that exploited the tension between America’s love of individualistic freedom and its Hooveresque obsession with law and order, and, in the last gasps of the Old Left, scathing message films about the fascistic power of the cornpone, jes’-folks common man when amplified by the ever-expanding electronic media.

The latter style found its apotheosis in A Face in the Crowd (1957), directed by ex-Red and “friendly witness” to HUAC Elia Kazan. Hoberman concludes An Army of Phantoms with a close reading of this hysterical, terrifying film, which posits Andy Griffith as a monstrous, Huey Long version of the beloved folksy bumpkin seen on his long-running TV show. Noting how Griffith’s character, Lonesome Rhodes, embodies many of the (often contradictory) icons discussed in the book—Hitler, John Wayne, Marlon Brando (of The Wild One), Davy Crockett, and Elvis—Hoberman shows how far we’d come in the years following The Next Voice You Hear. In that film, America is united by the straight-talking voice of God on a radio in a church; in A Face in the Crowd, the country is bamboozled by a cynical hick on TV in its living rooms, abetted by Madison Avenue and the religion of consumerism. Advertising, not social realism, was the new propaganda. Needless to say, this is still true today.

Indeed, one of the many virtues of An Army of Phantoms is how assiduously Hoberman collects prequel moments to our contemporary national fissures. A sampling: Ayn Rand’s 1947 Screen Guide for Americans, which issued a series of prohibitions for screenwriters and directors, including “Don’t Smear Industrialists, Don’t Smear Wealth, Don’t Smear Success . . . Don’t Deify ‘The Common Man’”; the National Security Council Report 68’s warning that to defend freedom, it will be necessary to reinforce and expand the security state; Senator William Jenner shouting, “Our only choice is to impeach President Truman and find out who is the secret invisible government which has so cleverly led our country down the road to destruction”; Adlai Stevenson’s acceptance speech for the 1956 Democratic presidential nomination: “This idea that you can merchandise candidates for high office like breakfast cereal—that you can gather votes like box tops—is I think the ultimate indignity to the democratic process”; an FBI informant reporting “demeaning portrayals of bankers” in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946).

In late-’40s and early-’50s America, the Dream Life was consumed by nightmares of alien others and invisible traitors; Hoberman leaves us with the question of whether we ever woke up. Thankfully, he’ll stay on the case for the third installment, Found Illusions: The Romance of the Remake and the Triumph of Reaganocracy, currently in progress.

Andrew Hultkrans is the author of Forever Changes (Continuum 331/3, 2003).