“As smoking gives us something to do with our hands when we aren’t using them,” Dwight Macdonald wrote in 1957, “Time gives us something to do with our minds when we aren’t thinking.” What leads us here, Macdonald asks, to the banal, boxed trifles of popular journalism? What, exactly, is to be gained by a three-hundred-word once-over of “World News”? Do we seek, as Macdonald concedes to be Time’s singular benefit, “practice in reading”? Perhaps we crave immersion in a warm bath of facts, to “have the little things around, like pets,” to collect “them as boys collect postage stamps.” Macdonald spent years laboring in the fact-friendly Luce empire as a writer at Fortune, no doubt watching his paragraphs hacked apart, the perfect verb sacrificed on the altar of snappiness, the clauses chopped into the staccato anti-rhythms of “readability.” Buy it if you like, was Macdonald’s position. But don’t call it edification.

If the pointless accumulation of facts was taken to be some sort of mental tonic, and time spent with The Ed Sullivan Show assumed to be wasted (you could have been reading Time!), Macdonald blamed a particularly American reverence for the scientific method. What happens in a three-minute nightly news segment is in some sense subject to verification and thus accorded a certain respect: true trash over untrue trash. The confusion of soft spin for hard news, of light entertainment for intelligent engagement, did not begin with the genesis of Fox News. (As a reviewer of books, I am duty bound to declare, once per piece, that some contemporary phenomenon is “not new.”) But such contemporary resonance, such chance persistence of fact, is not what shimmers in Masscult and Midcult, a newly reissued collection of Macdonald’s finest essays.

Even in his early Marxist days, Macdonald was an aesthete first; Trotsky’s jeremiads, he liked to point out, had style. What distinguishes Macdonald from his contemporaries is not accuracy, or relevance, or especially trenchant insight. What distinguishes him is that once he got hold of a fact, true or otherwise, he knew what to do with it.

There was, for instance, the fact of Life, Time’s photo-heavy sister publication in the middlebrow empire of Henry Luce: a “typical homogenized magazine,” the same issue of which will present a “serious exposition of atomic energy,” a “disquisition on Rita Hayworth’s love life,” “nine color pages of Renoir paintings,” and “a picture of a roller-skating horse.”

Defenders of our Masscult society like Professor Edward Shils of the University of Chicago—he is, of course, a sociologist—see phenomena like Life as inspiring attempts at popular education—just think, nine pages of Renoirs! But that roller-skating horse comes along, and the final impression is that both Renoir and the horse were talented.

Such observations in the pages of the Partisan Review got Macdonald called the “high priest of culture snobs” by trend-spotting journalist Alvin Toffler in the pages of Life. (Toffler goes on to state that Macdonald’s brand of criticism is “hardly new.”) I’m not sure about “snob,” which smacks of a certain anxious striving, but there was something of the sacerdotal in Macdonald, some drive to defend the faith. It worried him that intelligent people thought Our Town a great play, late Hemingway great literature, the architecture of Yale University a first-rate example of the architecture it strives to be. (Yale, he wrote, “is more relentlessly Gothic than Chartres, whose builders didn’t even know they were Gothic and so missed many chances for quaint effects.”)

Macdonald was not especially fond of lowbrow amusements (what he called “Masscult”), but, then again, few people thought Norman Rockwell an artistic genius. The “Midcult” cultural products mentioned above were, on the other hand, designed with a kind of sinister ambiguity that led people to confuse them for high art. The pretension of Midcult provoked what Louis Menand calls, in a nuanced introduction, “Macdonald’s lifelong hatred of bogus authority.” Middlebrow’s great sin was that it pretended to be otherwise. The nation’s great sin was that it didn’t know the difference. There was a fact, Macdonald thought, about the greatness of Melville, a fact about the superiority of Poe over the hack mystery writers of his day. These were the certainties he cared about, and the certainties he thought on the verge of extinction.

Are facts so fragile? The essays here are the work of a burned-out ideologue with a dysfunctional relationship to conviction. He believed sincerely in Lenin until he did not, and in Trotsky until he gave him up, too. His anti-communism was at least as earnest as his communism had been. So, too, his left-leaning anarchism; he ran out of time before he could become disaffected with that. Macdonald enjoyed being on the outside, but any club that would have him was a club he would eventually find wanting. His teachers at Yale disappointed him. He left the communist left, left Fortune, left his wife. When he resigned from the Partisan Review in 1943, finding the magazine at which he’d labored for six years insufficiently opposed to American entry into World War II, it was generally agreed that Macdonald had started resigning the moment he joined the staff. Trotsky called him “a Macdonaldist.”

Though famously difficult, Macdonald was not in the least cloistered or antisocial. He relished the performance of his own contrarianism. During the university protests of the late ’60s, he tried mightily to get arrested and was jealous when the police picked up his friend Norman Mailer. Alcohol fueled his penchant for showmanship—asked by his second wife why he drank so much, he replied, quite logically, “I’m an alcoholic, goddamnit!” At the end of his life, tired but still game, he relied on shots of adrenaline to carry him through a full night of partying. He’d pop out the syringe, unembarrassed, in the middle of the revelry.

In defending his shifting sets of beliefs, Macdonald was prolific in the pages of whatever magazine he happened to be running. Michael Wreszin’s oddly entertaining biography of Macdonald, which makes copious use of the phrase “shouting match,” narrates a particularly ugly parent-teacher meeting in which Macdonald denounced the administration of his son’s elementary school for hosting “banal apologists for Stalinism” as speakers, was in turn denounced as a Trotskyist, and replied that only a Stalinist would use such dated terminology.

Episodes such as this suggest a life immersed in minor details, small heresies, and the narcissicisms such slivers of difference will tend to spawn. Macdonald had burned through a lot of facts by that time; at middle age, he settled into his role as the New Yorker’s resident naysayer. Recognition of past folly did not soften Macdonald—well after his break with communism, a biography he wrote of Henry Wallace, in the wake of Wallace’s independent (and, by most accounts, Communist-backed) run for the presidency on the 1948 Progressive Party ticket, was described as “etched in acid”—and it appears to have nourished a certain contempt for dupes.

Thus these essays take great pleasure in exposing what Macdonald thinks to be the shallow vulgarity of the public’s enthusiasms. Hemingway, we learn, for all his strengths, “strikes one as not particularly intelligent.” Tom Wolfe, whom Macdonald refers to as “Dr. Tom Wolfe (Ph.D., American Studies),” will not, he suspects, be “read with pleasure, or at all, years from now, and perhaps not even next year.” Even obvious objects of derision such as Luce are not too obvious for a thorough demolition job, complete with firecracking footnotes where an insult might otherwise disrupt the flow of prose.

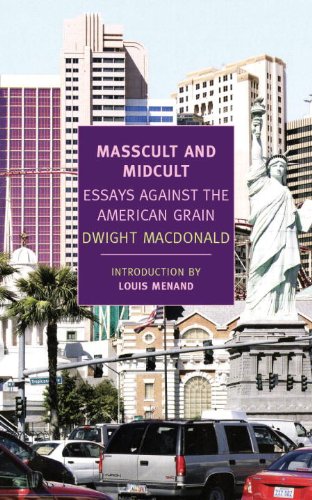

[[img:2]]

In the collection’s most revealing essay, Macdonald considers the ballyhooed 1952 release of the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, a then-new translation “authorized” by all the major Protestant denominations. It will surprise no one that, in Macdonald’s judgment, the translation comes up short. But the anatomy of this particular Macdonald takedown is less interesting than all the frustrations it dredges up from the depths of his psyche; in the tension between prose and poetry, accuracy and tradition, one finds all the frustration of being a prose stylist in a factoid-mad world.

The new Bible sought to reflect advances in biblical scholarship while remaining faithful to the unmatched prose of the King James Version, an admirable, if obviously contradictory, set of aims. Macdonald finds great pleasure in some of the Revised Standard Version’s clarifications; “Leah was tender-eyed, but Rachel was beautiful” now becomes “Leah’s eyes were weak, but Rachel is beautiful,” making sense of what had been a vexing line in Genesis. But he also finds, in the Revised Standard Version, all the vices of workmanlike prose that would have plagued him as he toiled as an editor at Fortune. The new version sounds like “a mother at a picnic,” like a “mortician’s ad,” like the dullest kind of service journalism. There is the prissiness that softens “virgins” to “maidens.” There is the impression that prose needn’t hew to a rhythm, and, in this case, the mutilation of rhythm for the sake of clarity. There is, above all, the drive to Spell It Out, wherein the reader is thought too dull for the indirection of metaphor. Even given the laudable goal of historical accuracy, Macdonald asks, when the two conflict, why privilege facticity over poetry?

Granting . . . that Job really put the price of wisdom above pearls and not above rubies, that the silver cord was “snapped” rather than “loosed, that the widow gave not her “mites” but “two copper coins,” . . . and that “my cup overflows” and “by the mouth of babes and infants” are more up-to-date locutions than “my cup runneth over” and “out of the mouths of babes and sucklings”—granting all this, it is still doubtful that such trivial gains in accuracy are not outweighed by the loss of such long-cherished beauty of phrasing. Might not the Revisers have left well enough, and indeed a good deal better than well enough, alone?

There is little in this collection that may not be summarized by the preference for a poetic, inaccurate seventeenth-century translation of a Hebrew text over a factual database of authorial intent. The Bible’s Revised Standard Version is clear, most certainly, but the thoughtless pursuit of facticity, and the corresponding quickness to dispense with poetry, suggests an unfavorable comparison with the age that produced King James and his Bible.

Masscult and Midcult is not without its words of praise, though these surface with difficulty and often with qualification—as when Macdonald tells us that Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is a masterpiece only after declaring that his friend James Agee led a “wasted, and wasteful, life.” The objects of Macdonald’s admiration are no less revealing than the targets of his scorn. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men manages to draw “poetry from journalistic description”; that is, the work transcends the facts out of which it is shaped. In its largeness of scope, Famous Men resembles Moby-Dick, which Macdonald had praised for its ability to build fact into art, “a happy Triumph of the Fact: from an intense concern with the exact ‘way it is,’ a concentration on the minutiae of whaling that reminds one of a mystic centering his whole consciousness on one object, Melville draws a noble poetry.” This is how facts rise above trivia; a knowing voice makes something of them. Without the voice to give shape to the thought, you might as well be reading the undersides of bottle caps, or that tightly packaged collection of bottle-cap-worthy facts, Time.

It’s odd, then, that this collection concludes with what is essentially a fact-checker’s report on a single article of Tom Wolfe’s. Macdonald thinks Wolfe not so much a hack as a huckster, someone who has convinced a bunch of needy readers that he feels the pulse of an America they’re too old and feeble to understand. The article in question takes as its subject the New Yorker, concerns Macdonald’s friends, and does look to be full of fabrication, but Macdonald loses his essay in righting such wrongs—There was no such memo! Our memos, even imaginary ones, are not color-coded!—allowing Wolfe to dictate his direction and ending up nowhere in particular.

What’s really upset him is Wolfe’s style—the ellipses, the exclamation points, the italics—which Macdonald thinks, in 1965, already seems tired. Wolfe, he concludes, will seem hopelessly dated by 1966. (Accused by Macdonald of “parajournalism,” Wolfe might well have replied that nothing dates an essayist so quickly as the attempt to introduce a phrase—Midcult, Masscult—that never quite catches.) As is his habit, Macdonald proceeds from personal annoyance to societal diagnosis: It’s not just Wolfe, it’s this thing “parajournalism,” a “bastard form” that exploits “the factual authority of journalism and the atmospheric license of fiction.” Tom Wolfe’s stylistic tics, the roller-skating horses of serious investigative journalism, sugar the medicine of long-form reading, but dilute it as well. “He takes the middle course,” avers Macdonald, “shifting gears between fact and fantasy, spoof and reportage, until nobody knows which end is, at the moment, up.”

It would be a mistake to hold Macdonald to the rather Luce-ian standards he seems to echo here. He complains that Wolfe’s facts are for the most part not verifiable, but nothing of note in Macdonald’s collection can be confirmed with a phone call. It’s hard to say how one would go about verifying so sweeping a statement as “books that are speculative rather than informative . . . sell badly in this country,” but to purge speculative generalization from the piece would seem unwise. A careful, empirical Macdonald is no good to anyone. There are times in his essays when one doesn’t know where one is being led—which end is, at the moment, up—but if “up” is always marked clearly as such, the essayist in question is failing to essay at all.

Macdonald, who had no problem deeming any problem “the real problem of our day,” deemed the real problem of his day “how to escape being ‘well informed,’ how to resist the temptation to acquire too much information (never more seductive than when it appears in the chaste garb of duty), and how in general to elude the voracious demands on one’s attention enough to think a little.” That a well-informed citizenry was probably not the most pressing issue facing the nation in 1957 seems entirely beside the point. “You’re the boss, not the Facts,” Macdonald wrote, at the end of his life, to a young biographer in search of advice. Ignore information that you don’t wish to shape. “Be a literary man.”

Kerry Howley is a provost’s visiting writer at the University of Iowa.